Oklahoma Bar Journal

Women in Law

With introductions by Melissa DeLacerda and Retired Judge Stephanie K. Seymour

Reflections on Leading the Way

By Melissa DeLacerda

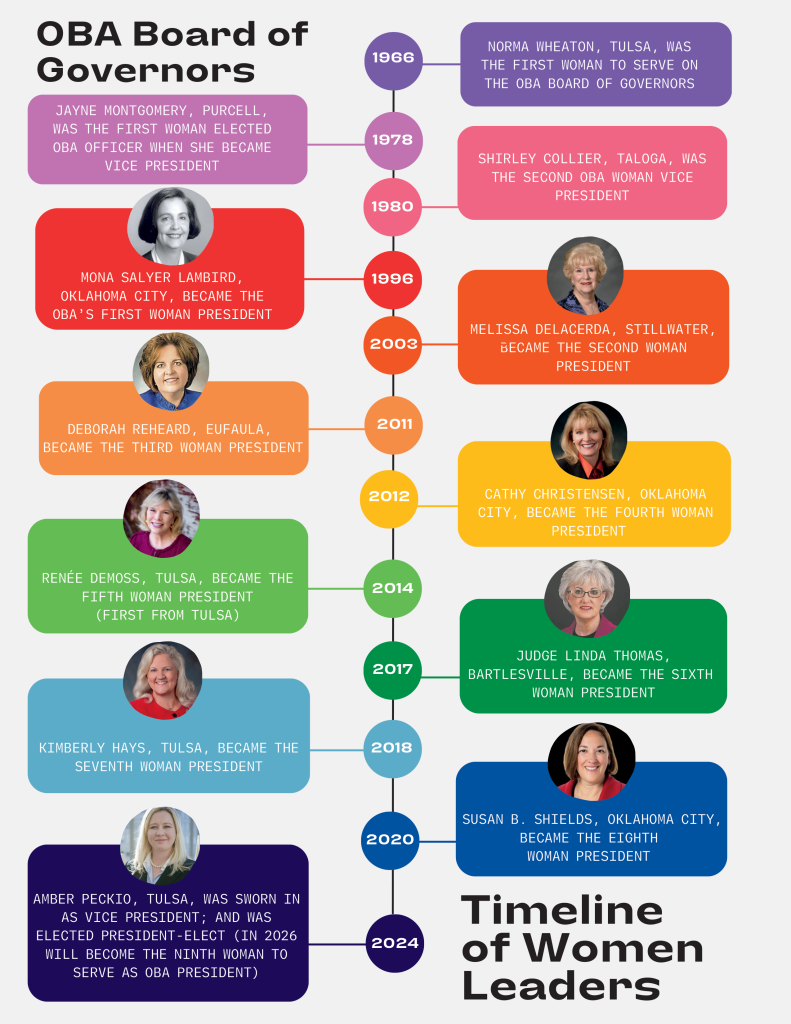

In 2003, we published the book Leading the Way: A Look at Oklahoma’s Pioneering Women Lawyers. At the time that book was published, only two women had served as OBA presidents (the first, not until 1996), and two women had been members of the Oklahoma Supreme Court throughout the OBA’s history.

Now, a little more than 20 years later, we have had six additional OBA presidents who are women. For the first time, the number of female law school students is equal to, or more than, the number of male students enrolled, and the number of women lawyers who are associates in large firms is equal to the number of male associates. The exponential growth of women in the legal field in the past century is a remarkable accomplishment.

The notable women attorneys featured in this issue broke barriers, gained the respect of their male counterparts and clients and highlighted the importance of diverse perspectives in the legal field. It is important that we continue the momentum, expanding the roles women hold in the legal field,

allowing today’s women lawyers to continue carrying the torch that the women before us held.

We dedicate this month’s publication to Oklahoma’s pioneering women lawyers. This issue of the Oklahoma Bar Journal serves to remind us, to inspire us and to honor those notable women who tread bravely into a world where a path for them – and others – didn’t yet exist.

Melissa DeLacerda is an OBA past president (2003) and the current chair of the Oklahoma Bar Journal Board of Editors.

Introduction

By Retired Judge Stephanie K. Seymour

In 1898, Laura Lykins was the only woman lawyer in Indian Territory.[1] In 1930, Grace Elmore Gibson was a lawyer and a part-time judge before she had the right to serve on a jury. By 2002, women made up approximately a quarter of the active Oklahoma bar.[2]

In 1898, Laura Lykins was the only woman lawyer in Indian Territory.[1] In 1930, Grace Elmore Gibson was a lawyer and a part-time judge before she had the right to serve on a jury. By 2002, women made up approximately a quarter of the active Oklahoma bar.[2]

In the first century of women practicing law in Oklahoma, there were many advances, and we reached many milestones. It is important for us to look back and remember what these pioneering women accomplished so that we may learn from their vision and perseverance as well as appreciate their achievements. My young law clerks were often surprised to hear about what it was like in "the old days" – by which they meant, of course, the 1970s – and to contemplate a professional world in a reality so recent but so startlingly different from what they saw in their law school and law firm experiences at the beginning of the 21st century. It is important that new generations discover the past and remember that they are only in the middle, not at the end, of the journey begun by a handful of amazing women in the late 19th century. They must learn to emulate the women they will read about in this journal and to continue their work, for there are many battles yet to fight. This is not a new sentiment. In 1894, Susan B. Anthony wrote:

We shall someday be heeded, and when we shall have our amendment, everybody will think it was always so, just exactly as many young people believe that all the privileges, all the freedoms, all the enjoyments which women now possess always were hers. They have no idea of how every single inch of ground that she stands upon today has been gained by the hard work of some little handful of women of the past.[3]

This journal tells a wonderful set of stories. They are the stories of Oklahoma women who fought for every single inch of ground we stand on today. These are women of character who made great strides in difficult times.

For example, in Oklahoma Territory in 1890, a law was enacted that stated: "The husband is the head of the family. He may choose any reasonable place or mode of living and the wife must conform thereto." Amazingly, this law is still on the books.[4] Although a 1986 attorney general advisory opinion found the statute unconstitutional, and although it has come before the Oklahoma Supreme Court more than once, the law remains.[5] When the Oklahoma Constitution passed, it was considered a very progressive one, but even so, it left many battles for the women of the state to fight. It was not until 1918 that State Question 97 passed by 25,000 votes, allowing women to vote. It was not until 1942 that a woman could hold state office. It was not until 1951 that Oklahoma afforded women the right to serve on juries. Only when federal law required it in 1974 did Oklahoma allow a wife to sue for loss of consortium.

In 1924, Bertha Rembaugh wrote an essay on the topic of "Women in the Law" for the first issue of the New York University Law Review. She wrote:

[I]s there a subject? Is there anything to say about women in the law, or women in relation to the practice of law, any more or different than there is to say of men in the law? One's first and immediate reaction is, of course, that there is not; that the relation of the individual woman practitioner to the law is the relation of an individual rather than of a member of a class; that there are no generalizations to be made about the woman lawyer as such.[6]

She went on to catalog the problems, challenges, achievements and general progress of women in the law and concluded with this thought: "As far as I know there is no woman general counsel for a railroad or an oil company ... When there is – as there will be – my subject will have completely ceased to exist."[7] She was perhaps a bit ahead of her time but sadly also a bit over-optimistic.

In 1961, the year before I started law school, only 316 women graduated from law school out of 11,220 graduating students.[8] There were three women sitting on the federal bench, the only three that had ever been appointed to that position.[9] In my law school class in 1962, I was one of 23 women out of 580 students. There were no women law professors, and one of the professors refused to call on women except once per semester when he conducted "ladies’ day" and called only on the women students. When I began practicing law in 1965, I only knew of eight other women who were then in the practice of law in Tulsa. At the Tulsa County Bar picnic that summer, the entertainment after dinner was a stripper!

The face of the legal profession in Oklahoma and across the United States has changed dramatically in the years since I became a lawyer. In 1965, for example, no women graduated from the OU College of Law. Likewise, neither OUC nor TU has any record of a female law graduate that year. In the 1970s, women began attending law schools in much greater numbers. Now, more than 50% of law students across the country are female.[10] In 1996, when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg came to speak at the Women in Law Conference in Tulsa, Roberta Cooper Ramo had just become the first woman president of the American Bar Association, Mona Salyer Lambird was the first woman president of the Oklahoma Bar Association, Millie Otey was immediate past president of the Tulsa County Bar Association, I was the first woman chief judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit, and Justice Yvonne Kauger was about to become the second woman chief justice of the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

There are still barriers to overcome. Those that lie ahead are in some ways more pernicious and, consequently, perhaps more difficult to take on. For example, we now see the persistence of the so-called "mommy track." So despite the great hopes of Bertha Rembaugh, the subject of women in the law does still exist. The Oklahoma Bar Association celebrates that subject in this journal.

Note: This introduction was originally published in the 2003 book Leading the Way: A Look at Oklahoma’s Pioneering Women Lawyers. It has been slightly modified with Judge Seymour’s permission for republication in this issue of the Oklahoma Bar Journal.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stephanie K. Seymour was the first female judge appointed to the 10th Circuit U.S. Appeals Court in 1979. She served as chief judge from 1994 until 2000.

ENDNOTES

[1] K. Morello, The Invisible Bar: The Woman Lawyer in America: 1638 to the Present, 2-38 (1986).

[2] “2002 Oklahoma Bar Association Membership Survey Report,” 73 OBJ 3402 (Dec. 7, 2002).

[3] History of Women's Suffrage 233 (E. Stanton, S. Anthony, M. Gage and I. Harper, eds. 1981-1922).

[4] Okla. Stat. tit. 32, §2.

[5] Janice P. Dreiling, "Women and Oklahoma Law: How It Has Changed, Who Changed It, and What is Left," 40 Oklahoma Law Review. 417, 418 (1987).

[6] Bertha Rembaugh, "Women in the Law," 1 NYU Law Review, 19, 19-20 (1924).

[7] Id. at 23.

[8] Stephen G. Breyer, Foreword to Judith Richards Hope, Pinstripes & Pearls, at xxiii (2003).

[9] Id. at xix.

[10] American Bar Association, Legal Education and Bar Admission Statistics, 1963-2003, available at www.abanet.org.

Mirabeau Cole Looney

Mirabeau Cole Looney

Mirabeau Lamar Cole Looney was born Jan. 16, 1871, in Talladega County, Alabama, to William Isaac Cole – a Gatesville, Texas, lawyer – and Martha (Mattie) Ann Nixon.[1] She was named after Mirabeau B. Lamar, the second president of the sovereign Republic of Texas.[2] It is believed the Cole family moved to Robertson County, Texas, around 1880 because the census from that year shows a Lamar Cole living on a farm with her mother; her brothers; her mother's brother, William A. Nixon; and her grandmother, Talitha Walston Nixon.[3]

Ms. Looney's interest in the law surfaced early in her life, and she could often be found reading her father's tan calf law books or fictional accounts of trials. Paralleling her interest in the law was her interest in civil government and history – interests that would serve her well in later years.[4]

In 1891, she married "Doc" Tourney Looney in Texas. Shortly thereafter, the young couple crossed over the Oklahoma line into the future Greer/Harmon County in the southwestern part of Oklahoma Territory and settled in what would later become the Looney community, named after the family.[5] The Looneys filed for a 160-acre homestead in December 1897 in Greer County, where they would begin their family[6] and where Doc Looney would become one of the earliest postmasters in the new area.[7]

While still a young man, Doc Looney died, leaving his wife with five children under the age of 10 to raise alone.[8] It is not known whether she sold the family farm or just left the land, but the patent was canceled by ruling on June 21, 1900.[9] To put food on the table, she taught music for a year and then saw the opportunities inherent in becoming a landowner. She filed a claim on a quarter section of government land one mile from Hollis, traded her organ for a team of mules and set about building a sod house on the hard-baked prairie soil.[10]

With courage of the "chilled steel variety" and "fires of determination glinting in her blue eyes," Ms. Looney started digging her own dugout.[11] The basement home where the family lived for the first year was four feet deep and lined with boards that stood on end and capped with a shingle roof.[12] Once the home was complete, Ms. Looney drove her mule team 13 miles to the Red River, where she cut the posts that would form a fence around her quarter section of land. If the posts were too heavy for her to lift into the wagon, they were dragged by a mule onto the wagon. Part of the fence built by Ms. Looney was still standing in 1921.[13] She planted her first crop of 20 acres in blowing sand with her 10-year-old son holding on to and guiding the plow handles while she drove the mule team.[14]

After the children were in bed that first night, Ms. Looney went outside and walked around the new sod house in the moonlight and would later say, "Nothing I have ever lived in since has seemed so grand as that place did that night."[15] The next day, before going to El Dorado to buy a windmill, she traded two of their 12 cattle and gave notes for an organ. Once the sod house was finished and the crop was in, Ms. Looney would again teach music lessons. With the money from those lessons and the crop, she purchased a two-room frame shack that she had moved to the farm. As she would later say, "We never felt richer than when we settled in our two-room house, with a new organ to take the place of the old one, and a windmill to lighten the labor of drawing water for the stock."[16] The family lived and worked on the farm for five years, the amount of time required to prove their claim, and received the land patent on March 29, 1906.[17] After the five years were up, Ms. Looney moved the family to Hollis so that the children could attend better schools.

In 1912, Ms. Looney was elected registrar of deeds for Harmon County, the "first of a series of political triumphs that ... distinguished her as one of the state's most successful women politicians."[18] Completing her term, she was twice elected treasurer of her county[19] and, in 1916, was elected Harmon County clerk for two terms.[20]

Since Ms. Looney maintained that she was a staunch Democrat but not a politician, a group of her friends got together to discuss her entrance into the Oklahoma Senate race and, believing that she could win, encouraged her to enter the race. Her friends then went to Mangum to discuss the plan with the "boys," finally convincing them that a woman could serve in the Legislature.[21] In 1920, Ms. Looney entered the Democratic primary as a candidate for state senator.[22] Since she had not finished her term as county clerk when the campaign for the Senate seat started, she told everyone she was "paying strict attention to being county clerk."[23] She continued by saying, "I refuse to slacken or neglect anything. My books shall be turned over in perfect order."[24]

During her Senate campaign, one of her supporters was asked, "Aren’t you afraid to match a woman against the politicians in the Senate?" The supporter smiled and replied, "They won't get anything by her."[25] Ms. Looney campaigned only in Greer County, covering the county in her own car, and had campaign expenditures totaling $149.80.[26] Ms. Looney, elected as a Democrat from the 4th Senatorial District for Harmon and Greer counties, not only carried her own Harmon County 3-1, but she also carried her opponent's county 2-1. Thus, she was seated the first woman in the Oklahoma Legislature.[27] She maintained the distinction of being the only woman to be in the state Senate until 1975.[28] Her daughter, Mabel Looney Parks, remembers going door-to-door seeking votes for her mother and recalls the comments of several men regarding the election. "Ms. Looney, I know you are a capable lady, but I believe a woman's place is in the home." Her response was, "Eating what?"[29]

On Jan. 4, 1921, Ms. Looney took her seat in the Oklahoma Senate, wearing a "smart brown suit and a brown hat, draped with a bit of lace veil." In an interview, she said, "There is nothing extraordinary about me."[30] But none who knew of her past would agree with that statement. The new senator had a "chain-lightning mind of a type essentially masculine," idealistically practical[31] and was a surprise to her fellow senators. One senator said: "It is easy to prophesy that she will prove a 'good sport,' cooperate well, work hard, realize her mistakes with a smile – and never weep. She has a good chance of becoming a 'fixture' in the Senate since she has a political future in mind and has in the past pleased her constituents."[32]

At the time of her election to the Senate in 1921, Ms. Looney expected to be admitted to the bar within the year, but she was not admitted until Dec. 10, 1923.[33] Her application, number 2139, was by motion directly to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, and her admission was granted by Chief Justice J. T. Johnson. She was 52 when she was admitted to the bar.[34]

While serving in the Oklahoma Senate, Ms. Looney was chairman of the State and County Affairs Committee, the Prohibition Enforcement Committee and the Agriculture Committee.[35] She also served on the Education, Hospitals and Charities, Penal Institutions, Public Service Corporations and Roads and Highways committees.[36]

In 1926, after serving three terms in the state Senate, she considered running for lieutenant governor of Oklahoma. Investigating the possibility of winning that election, she decided the courts would sustain the Oklahoma constitutional requirement that a man hold the office, and she abandoned the race. Realizing that Oklahoma courts and lawmakers had no control over federal offices and there were no limitations based on sex, she shocked the political establishment by announcing her candidacy for the U.S. Senate.[37] Her campaign slogan was, "Let Oklahoma be first and elect one of her qualified and legislative tried women to the U.S. Senate."[38] Although she was indeed a proven legislator, the newspapers wrote varied comments about her race. "The men of the Democratic Party organization are talking now of trying to get two of the three male candidates to withdraw from the race for U.S. Senator; otherwise they say Ms. Looney may walk away with the nomination."[39] "Ms. Lamar Looney's senatorial aspirations are unlikely to take her to Washington. However this sojourn on the sidelines has taught us that a woman is unlikely to be chosen for any place for which men clamor."[40]

Positive comments also appeared in some papers. "Ms. Looney won respect for her political acumen and legislative judgment while she served in the state Senate. She is not an exponent of freakish measures and her friends say she would grace the U.S. Senate."[41] "A political observer says to the credit of Ms. Lamar Looney, senatorial aspirant, that she never asks for favors on the grounds that she is a poor defenseless women; which suits us pretty well. Whether a candidate is man or woman has little bearing on fitness for parliamentary positions. Sex does not determine one's knowledge of governmental affairs."[42]

After losing her bid for a spot on the ticket for the U.S. Senate, Ms. Looney ran and won her fourth and final term in the Oklahoma Senate in 1927.[43] During her four terms in the Senate, Ms. Looney championed farmers and their need for more roads between cities and counties. Education and schools were also of particular interest to her, and she stood fast in the belief that each district should have the option to vote in favor of enough tax to ensure good schools in the district, with better equipment and instruction. She was interested in making government more efficient and went so far as to suggest that the number of representatives and senators in the state Legislature be reduced and the costs of government should be reduced by 50%. She was for prohibition, the World Court and the League of Nations. She favored the universal draft, conscription of wealth and property, and manpower.[44] She also believed that Oklahoma held possibilities for vast industrial development and encouraged the offer of inducements to industries.[45]

Ms. Looney also wanted laws protecting working women and children, along with ways to ensure their strict enforcement.[46] Although she believed in a generous policy with soldiers, she said she believed as William Tecumseh Sherman did on the issue of war, "We should exhaust all diplomatic and legal means of avoiding it and then, if we can avoid it only at the cost of honor."[47] She did believe in the enforcement of the payment of war debts but "was not in favor of playing Santa Claus to the foreign nations."[48] Her concern for the elderly was seen in her belief that their homes should be exempt from taxation.[49] In the financial arena, she thought we needed a different system of money and wanted the government to strike more money and do away with the Federal Reserve System.[50] She wanted the government to provide 20-year home mortgages at 2% or 3%.[51] Perhaps because it was an issue when she tried to run for lieutenant governor, but likely because she also championed women's rights, Ms. Looney pushed for legislation that would allow women to serve in state offices.[52] Although the constitutional amendment was not adopted during her lifetime, Ms. Looney was instrumental in starting the drive to get women qualified for all state elective offices.[53] After two failed attempts to have the Constitution amended, in a 1942 general election, SQ 302 was adopted, which allowed women to run for state offices.[54] She was also actively involved in the campaign giving women the right to vote.[55]

During her years as a senator, when the Senate was not in session, Ms. Looney worked for Co-Operative Publishing Co. of Guthrie as a traveling salesman of books and supplies used in public offices.[56]

Mirabeau Lamar Cole Looney died Sept. 3, 1935, and the flags flew at half-staff over the state Capitol in her honor. Her casket was placed in state in the Capitol rotunda.[57] She was honored posthumously at the annual statehood dinner of the Oklahoma Memorial Association on Nov. 16, 1935, along with Wiley Post and Will Rogers.[58] At the dinner, Camille Nixdorf Phelan’s Oklahoma History Quilt was presented to the Oklahoma Historical Society with a panel depicting Ms. Looney as one of Oklahoma's prominent women.[59] The quilt still hangs at the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Perhaps words from a Daily Oklahoman editorial best describe Ms. Looney:

It is those who served with Ms. Lamar Looney in the Oklahoma Senate who can render the truest testimony to her complete devotion to the public interest. She had an unusually high conception of the duties of a legislator and she served her people with a fidelity that never faltered or weakened. Oklahoma has never had a public servant who tried harder to serve the people well. She was never soiled by the sordid political currents which have soiled so many political officials. She was a womanly woman when she entered official life, and she was a womanly woman when she cast off her official cares. She was sufficient answer to the current assertion that a really fine woman had better let politics severely alone. Women who enter politics should study well the high example set by Ms. Looney.[60]

After caring for and educating her children and watching them leave home, Ms. Looney once said, "I have time now to set a stone rolling for the good of humanity, if I can."[61] And that she did.

ENDNOTES

- Clarence Wharton Cole

- Mabel Looney Park

- Patricia Sellers Dennis

[1] Clarence Wharton Cole, nephew of Lamar Looney, information furnished to author by Patricia Sellers Dennis, great-granddaughter of Lamar Looney, June 27, 2002.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Mabel Looney Park, daughter of Lamar Looney, information furnished to author by Ms. Dennis, June 27, 2002.

[6] Cole.

[7] Park.

[8] Id.

[9] Cole.

[10] "Hollis Woman First Ever to Sit in Senate Hearing Impeachment Charges against a Governor," The Daily Oklahoman, Oct. 9, 1923, pg. 1.

[11] Vivian V. Sturgeon, "Clerk of Harmon County Wins Senate Seat and Plans Political Future," The Daily

Oklahoman, Dec. 5, 1920, pg. 1.

[12] Cole.

[13] Id.

[14] Sturgeon.

[15] Cole.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] "Hollis Woman."

[19] Id.

[20] Cole.

[21] "Hollis Woman."

[22] Patricia Sellers Dennis, great-granddaughter of Lamar Looney, telephone conversation with author,

Nov. 13, 2002.

[23] "Hollis Woman."

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Dennis, telephone conversation with author.

[29] Park.

[30] Sturgeon.

[31] Id.

[32] "Hollis Woman."

[33] 95 Okla. Reports xxiv, Harlow Pub. Co., Okla. City, Okla., 1923. Listed on the "Roll of Attorneys” admitted from

Nov. 1, 1923, to March 1, 1924.

[34] Dennis, telephone conversation with author.

[35] Park.

[36] Dennis, telephone conversation with author.

[37] Id.

[38] Cole.

[39] Park.

[40] Id.

[41] Park.

[42] Id.

[43] Cole.

[44] Id.

[45] Sturgeon.

[46] Id.

[47] Id.

[48] Cole.

[49] Id.

[50] Id.

[51] Id.

[52] Dennis, telephone conversation with author.

[53] "Hollis Woman."

[54] Oklahoma Almanac: 1999-2000, Okla. Dept. of Libraries, Okla. City, Okla., 1999, p. 666.

[55] Park.

[56] Cole.

[57] Patricia Sellers Dennis, letter to author, Nov. 18, 2002.

[58] Cole.

[59] Dennis, telephone conversation with author.

[60] Park.

[61] Sturgeon.

Jessie Randolph Moore

Jessie Randolph Moore

Jessie Elizabeth Randolph Moore was born on a plantation in the Chickasaw Nation, Panola County (now Bryan County), on Jan. 30, 1871, to William Colville Randolph and Sarah Ann Tyson Randolph. In 1874, her parents – along with 10 other families – moved to the White Bead Hill region north of the Washita River in what was then Pontotoc County. They established the Randolph settlement north of what is now Maysville. Ms. Moore first attended school in a log schoolhouse built on the Randolph ranch, but the family later moved to Gainesville, Texas, where she attended school at St. Xavier Academy in Denison, Texas, and later Kidd Seminary at Sherman, Texas. Kidd Seminary was known as the "alma mater for the daughters of many prominent families from the Indian Territory."[1]

In a 1926 election, which she won by a handsome majority, Ms. Moore became the first woman elected clerk of the Oklahoma Supreme Court and Criminal Court of Appeals. With the victory, she also became the second woman in Oklahoma history elected to a state office. She served in that position until 1931. Of her bid for a second term as clerk, an article in Harlow's Weekly stated that to hold the office was "something to be justly proud of. But to have filled that office with success and credit and to have it truthfully said that you have kept the faith is something to be more than proud of; because the voters of the state have helped to make the first possible, but to have given satisfying service from this office is fulfilling a sacred trust, and something that rests entirely upon the shoulders of the person elected to the office."[3] Elaborating on the duties of the office, it was noted that more than 1,000 new appeals were filed each year, and Ms. Moore was responsible for the maintenance of all briefs, records and petitions. She was also required to answer all requests for information from attorneys. Otherwise, she said, the lawyer "situated at a distance from the state capitol is discommoded."[4] The article described the Supreme Court Clerk's Office as one of the busiest offices at the state Capitol, saying that Ms. Moore "continues daily to wait upon 22 law clerks from three high courts, as well as the Supreme Court referee and the constant stream of lawyers visiting her office for information regarding their cases."

In an article printed during her reelection campaign, it was noted that Ms. Moore was one of the emancipated women able "to grasp the opportunities offered by the political field" and make good proving that "a woman [could] fill a state office efficiently."[5] It was further noted that she "[had] made a success of her position because she was not afraid of hard work and responsibility." The article credited her dedication and the example she set for "placing the women of the state on firmer ground in holding public offices.” “She served 10 years as clerk in the office in a manner so outstanding that the Supreme Court admitted her to the practice of law in 1923."[6]

In 1927, she sponsored and secured the passage of a bill through the Legislature that initiated a fixed initial deposit of $25 for the Supreme Court, which resulted in annual savings to taxpayers and litigants.[7] During that year, she also was ex officio secretary of the bar commission. In this position, she was responsible for managing all complaints against lawyers, overseeing disbarment proceedings and attending to the examination and admission of attorneys to the practice of law in Oklahoma.

She "was active in Democratic politics for many years, participating in various campaigns and for the party ticket in general elections."[8] She was instrumental in the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt when she served as a Democratic presidential elector in 1940 and 1944. Ms. Moore also spearheaded Indian participation in the campaign when Robert S. Kerr ran for and was elected governor.[9] She served as director of the Bureau of Maternity and Infancy of the state health department and was named by then-governor W. H. "Alfalfa Bill" Murray to head the first Women's Division of the Federal Emergency Relief Organization in Oklahoma County. Ms. Moore planned and organized the statewide rollout of the organization so successfully that her plan was "adopted and put into force on a nationwide scale by the federal government in 1933."[10]

Being of Chickasaw blood, Ms. Moore served as a member of the Chickasaw Tribal Counsel under the late Gov. Douglas H. Johnston of the Chickasaw Nation and later Gov. Floyd E. Maytubby. One of her last efforts and honors on behalf of the Chickasaw Nation and "Indian historical interests was when she served as an official representative for the Chickasaw Nation in ceremonies in Memphis, Tenn., dedicating the newly formed Chickasaw Wing of the U.S. Air Force on Sept. 26, 1954."[11]

Ms. Moore was a charter member of the White Bead Presbyterian Church and remained active in the church after it moved to Pauls Valley. Members of her Sunday school class praised Ms. Moore as a wonderful teacher and Christian leader.[12] She was president of the Alternate Saturday Club and active in the Eastern Star. For her outstanding contributions in both private and public life, Ms. Moore was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame by the Oklahoma Memorial Association at its Statehood Day banquet on Nov. 16, 1937.

Although her legal, political and community contributions were impressive, a campaign article in Harlow's Weekly noted that Ms. Moore was not a politician but rather was the type of woman you would "expect to find presiding over church, Red Cross, literary and civic improvements meetings. You can easily picture her at the head of the dinner table in a Southern mansion. She is attractive, cultured and gracious; one recognizes immediately that she comes from Southern people ... She is unassuming, with a kind word and sincere friendliness toward everyone with whom she comes in contact ... the messenger boy gets as cordial a smile as does the biggest lawyer or the richest oil man."[13]

Ms. Moore was a poet at heart and displayed her ancestral pride in her literary endeavors. One of her works, "The Five Great Indian Nations," appeared in the autumn 1951 issue of the Chronicles of Oklahoma and depicted the part played by the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Choctaw, Seminole and Creek Indian tribes on behalf of the confederacy in the Civil War.[14] Another of her works, "Lines on an Indian Face," written in 1907, gives a "sensitive perspective on the decimation of the Native American culture."[15]

Following the death of Jessie Elizabeth Randolph Moore on Oct. 7, 1956, Muriel H. Wright wrote an article for the Chronicles of Oklahoma commemorating her life. Ms. Wright noted, "Oklahoma has lost one of its best loved and revered pioneer women. Ms. Moore was known far and wide over the state for her devotion and her contributions to the history of Oklahoma."[16] According to her obituary, Ms. Moore's contributions to public life made her one of the state's leading women in its development, as well as a guiding spirit in its attainments, and in the growth of the Oklahoma Historical Society, serving as a member of the Board of Directors for 37 years and as treasurer for 35 years, becoming a lifetime member in 1920. She possessed "fine executive abilities and staunch loyalty," and "yet her talents lay in her inquiring mind and her choice of words in expressing her thoughts."[17] Ms. Moore's pride in her Chickasaw heritage was recognized at her funeral, where she requested that the pallbearers be selected from persons of Chickasaw descent. Among the pallbearers were Chickasaw Nation Gov. Floyd Maytubby and Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Earl Welch.

At her funeral, Haskell Paul – of the pioneer Paul family of Pauls Valley – paid tribute to Ms. Moore as "one of Oklahoma's heroic women," saying she was courageous, generous and humble with a strong intellect. He noted that it was in Pauls Valley that she was first recognized for her great character, which would later be appreciated by all Oklahoma citizens. Mr. Haskell's mother, Victoria Paul, who had known Ms. Moore for 60 years, said she was always a lady who "could look the world in the face with a clear conscience."[18]

ENDNOTES

- Judge Candace L. Blalock

- Jayne N. Montgomery

- Judge Reta M. Strubhar

[1] Muriel H. Wright, "Jessie Elizabeth Randolph Moore of the Chickasaw Nation," Chronicles of Oklahoma, XXXIV (Winter, 1956-57), Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City, Okla., 1957, p. 393.

[2] Ex parte Bonitz, 30 Okla. Crim. 45, 234 P. 780 (Okla. Crim. App. 1925).

[3] Vetrus K. Hampton, "A Woman Masters a Big State Department," Harlow's Weekly, p. 5a.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] "Retired Court Clerk, Political Figure is Dead," The Daily Oklahoman, Oct. 8, 1956.

[9] Id.

[10] Wright, p. 394.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Hampton, p.394.

[14] Jessie Elizabeth Randol Moore, "The Five Great Indian Nations," Chronicles of Oklahoma, XXIX (Autumn 1951), Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City, Okla., 1951, p. 324.

[15] Judge Candace L. Blalock, letter to Judge Reta M. Strubhar.

[16] Wright, p. 392.

[17] Id.

[18] Id., p. 395.

Florence Etheridge Cobb

Florence Etheridge Cobb

Florence Etheridge Cobb was born in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on Sept. 20, 1878, to Samuel W. and Emma A. (Nichols) Etheridge. Her childhood was spent near Boston and Everett, Massachusetts, and she graduated from Everett High School on June 23, 1897. Although she was raised in New England, she did not appear to have a stilted manner or live by the customs of mid-Victorian Boston.

Because of her belief that women had the ability to succeed in activities outside the home, she pursued a legal education. She attended the Washington College of Law, where she received her law degree on May 26, 1911. On Oct. 3, 1911, she was admitted to the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia on a motion by Ellen Spencer Mussey.[i] Ms. Cobb continued her legal education, and on May 27, 1912, she received an LL.M. from the Washington College of Law. She was admitted to practice law before the U.S. Supreme Court on Jan. 29, 1915.

While living in Washington, D.C., she was employed at the Census Bureau, the Department of Commerce, the Division of Education and, finally, the Office of Indian Affairs. During her years in government service, she was elected treasurer of the Federal Employees Union in 1916, and from 1917 to 1921, she served as the fourth vice president of the National Federation of Federal Employees. Ms. Cobb was one of the few women in federal government service during these years and did her part in the "war of independence for women," according to an article in the Wewoka Times-Democrat.[2] She was a "revolutionist when it came to the question of woman's place, and proper amount of activity in the world outside of the home."[3]

Ms. Cobb's drive to establish the independence of women led her to organize the inaugural suffrage parade on March 3, 1913. This concerted effort on behalf of the women's movement came at a time when there was a "newer, more liberal, progressive administration under Woodrow Wilson ... and the Democratic Party was forced to take cognizance of the growing demand of women for a share in the government."[4] However, the conservatism of the Old South and New England forced many women suffragists to play the "role of unwanted martyrdom," as the press portrayed them as exhibiting unladylike attitudes of defiance while picketing the White House.[5]

During this same period, Ms. Cobb was appointed to the office of probate lawyer based on her work as a law clerk, where she consistently demonstrated her legal aptitude and ability. In 1918, she relocated to Vinita and became a U.S. probate attorney. After serving there for two years, she went to Seminole County and served in the same position for one year. Upon arriving in Oklahoma, she was admitted to practice law before the Oklahoma Supreme Court on June 3, 1918.

Settling in Wewoka, it was noted that there was an "unusual stir of chivalry among the pioneer legal practitioner who had any probate practice."[6] The gentlemen curtailed their rough-and-tumble tactics on days when she might be in court, but perhaps the unfailing show of courtesy in the courtroom made her wonder what might be going on behind the scenes. She was constantly on the alert as to "whether any unfortunate Indians were being defrauded of their lands secretly by old ruses."[7] In 1923, Ms. Cobb represented the intervener in a reported decision dealing with constitutional amendments, one of which was the so-called women's amendment, which would extend the qualifications of persons eligible to elective or appointive offices of the state to women.

On March 25, 1921, she married T. S. Cobb, a former county judge of Seminole County. He was one of the typical fighting, frontier-type lawyers, and she admired his spirit; he admired hers as well. After leaving the Indian Department, she continued practicing law with her husband and assisted him in his projects throughout his bouts with failing health.

Ms. Cobb "was a woman of considerable literary ability, and had she chosen an exclusively literary career might have risen to heights of distinction."[8] Even with her focus on her legal career, she did have many published poems and articles. Fostered by her intense interest in literature, Ms. Cobb helped form the Wewoka Writers Club, which may have explained her willingness to become a librarian for the Wewoka City Library.

Ms. Cobb also exercised her literary abilities when she and her husband produced The Gossip, a news sheet that championed the unpopular issues of the day and stood up for the underprivileged minority. After the death of her husband, she continued its publication and "was a champion of what she felt was right against corruption, politically and socially."[9]

Ms. Cobb's legal career was diverse. Besides practicing law, she served a term as justice of the peace in Wewoka, and for several years, she was a municipal judge for the city of Wewoka. During her tenure as judge, she prepared the charter and ordinances of the city of Wewoka for publication in 1935.

In 1922, Ms. Cobb became the Oklahoma chairman of the National Women's Party, and in 1924, she organized a convention for the Government Workers Council of the National Women's Party in Washington, D.C. She was also parliamentarian of the Federation of Women's Clubs and a member of the Women's Bar Association of Oklahoma, the National Institute of Social Sciences, the American Bar Association, the American Academy of Political Science, the American Economic Society and the Women Lawyers Club of New York. She was also listed in "Who's Who in America."

When Ms. Cobb died March 14, 1946, the Seminole County Bar Association resolved that "it has lost an honored and distinguished member of the bar, a positive and dynamic thinker who had the courage of her convictions, whose place in our association will probably never be filled during the lifetime of any of its present members."[10]

ENDNOTES

- Vance Trimble

[1] H.W. Carver, "Necrology: Florence Ethridge Cobb, 1878-1946," Chronicles of Oklahoma, XXV (Spring 1947), Oklahoma Historical Society, Oklahoma City, Okla., 1947, pp. 72-73.

[2] “Originator of Inaugural Suffrage Parade Passes," Wewoka Times-Democrat, March 15, 1946, p. 1.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Carver.

Grace Elmore Gibson

Born Aug. 8, 1886, in Kansas, Grace Elmore Gibson's life was dedicated to being involved in civic and community affairs and setting precedents for women in the legal profession.

Once she graduated from the University of Kansas and married Judge Nathan A. Gibson, she took up the study of law so she "could be a good listener when her husband talked."[1] Ms. Gibson was motivated to action following a conversation with her husband about a case he was handling. When she asked about the case, Judge Gibson commented, "I forgot for a moment that you don't understand law." It was shortly after that conversation that she enrolled in classes and began studying the law.[2] She soon realized she was interested in pursuing a legal career, not just to be a good listener but to practice law as well.

After completing her legal studies and being admitted to the bar in 1929, Ms. Gibson began practicing law in Tulsa's Court Arcade Building. Once she discovered she had a particular interest in cases dealing with the "human equation,"[3] Ms. Gibson developed quite a clientele in the area of domestic difficulties. When discussing the problems women encountered in those times, Ms. Gibson noted that being a wife was a difficult job and involved “expecting things of a man, believing he can do them, keeping an even keel in that most delicate of human relationships, and spending wisely.”[4] She said she found herself being a woman first and then a lawyer – not because he wanted it that way, but because her "colleagues were so acutely conscious that a woman was in the courtroom lawyering.”[5]

As all women from that era understood, the legal profession had been a man's profession and he was at home in it, but "he was not at home with women in it."[6] As the world watched women beginning to claim their rights in the legal profession, "the men watching ... [were] good sports about it."[7] Despite men's preconceived ideas of women in the workplace, Ms. Gibson always found her colleagues very courteous and gallant, perhaps more than she would have liked them to be. Ms. Gibson would say, "I am here as a lawyer, not as a woman, and I ask no odds because I am a woman. In the courtroom, men get up to give me their chairs, but I'd rather they wouldn't."[8] She saw a woman lawyer as a "concrete vocation of interesting actualities."[9]

When trying a case before a jury, she had only men to address since women had not yet been granted the right to serve on juries. In her dealings with male jurors, Ms. Gibson felt that how they viewed her depended on how they viewed their wives at home. If a man's wife was domineering at home, then he, as a juror, tended to see a woman lawyer pleading a case "as a bossy sort of a hussy and looked upon her with a resentful eye. She wasn't going to tell him what to do."[10] If a juror thought his wife was intelligent and respected her, he tended to treat the female attorney the same way. Ms. Gibson was concerned that women be granted the right to serve on juries because she, unlike many of her time, felt that women would add a new dimension to decision-making in jury trials. She was not concerned that, when they were granted that right, their emotions would make the decisions for them. She saw the topic of women jurors as "an abstract subject of interesting possibilities."[11]

In 1930, Ms. Gibson became the first woman to be elected to a county or district judgeship in Oklahoma when the Tulsa County Bar Association tapped her to replace vacationing Judge John Boyd for several weeks. In 1936, she was named by Gov. E. W. Marland to sit for Judge James S. Davenport on the Oklahoma Criminal Court of Appeals in the embezzlement case against E. M. Landrum, county judge in Vinita. This honor, believed to have never before been accorded a woman, led to the first opinion ever written by a female member of the Criminal Court of Appeals.[12] Presiding Judge Thomas A. Edwards and Judge Thomas H. Doyle concurred with Ms. Gibson's mostly technical opinion.

Perhaps the traits that made her one of the trendsetting female attorneys of her time can best be seen in her excerpts from the Landrum opinion:

This case comes before this court upon 12 assignments of error by the defendant. No good purpose can be served by setting out these assignments in detail. Suffice it to say that they formulate the real issues in this case to be as follows:

- Is the information duplicitous?

- Does the information state a public offense?

- Is the verdict in proper form to justify the sentence imposed?[13]

In the closing statements of the opinion, Special Judge Gibson noted that "the evidence might have justified a greater fine, and the defendant will not be heard to complain ... If error was committed by the trial court in this regard, it was in favor of the defendant, and he will not be heard to complain of it."[14]

In addition to her impressive legal career, she was actively involved in political and community affairs. In 1932, she made an unsuccessful bid for the U.S. House of Representatives on the Democratic ticket, running on a platform of “intelligence in legislation" and "economy in government." During World War II, she was director of the Women's Contact Corps of the Office of Civilian Defense, marshaling women to serve as volunteers in the civil defense area in Oklahoma. In 1944, Tulsa Mayor Olney Flynn appointed her to the position of city treasurer, the highest nonelective city post to be held by a woman up to that time.[15]

In a Tulsa Daily World article, Ms. Gibson said: "A man may do anything he likes, from steeple-sitting to ditch-digging, and nobody bothers to ask him why he did it. He might be asked how he did it, but he's seldom called upon to explain the reason why. But with a woman it's different. If she goes far afield from teaching, stenography or marriage, people want to know how come.”[16]

Grace Elmore Gibson, former city treasurer, civic leader, attorney and judge, died May 6, 1975, at the age of 88 in Tulsa.

ENDNOTES

- Barbara J. Eden

[1] "Mate's Problems Baffled Her so Tulsa Portia Took Up Law," Tulsa Daily World, Sept. 13, 1931.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] "Sentence Given Judge is Upheld," Tulsa Daily World, Aug. 8, 1936.

[13] Landrum v. State, 63 P.2d 994 (Crim. App. 1936).

[14] Id. at 997.

[15] "Woman Who Held City Office Dies," Tulsa Daily World, May 7, 1975.

[16] "Mate's Problems."

Ethel Kehrer Childers

Ethel Kehrer Childers was born Oct. 19, 1887, in Coal Hollow near Chanute, Kansas, to Mr. and Ms. Charles H. Kehrer. She and her six siblings were reared on an 80-acre farm 10 miles southeast of Chanute. She attended a country school near home, and at age 12, she took the examination for admittance into high school and passed with flying colors. After graduating from high school at 15, she obtained a teaching position at Coal Hollow. One day, after several encounters with students – many of whom were larger than she was – she took a rubber hose to 24 students who had disregarded her instructions. Three of them were children of members of the Board of Education. She feared for her job, but the board members respected her "straightforwardness of decision and resoluteness of character” and told her she had the job as long as she wanted it.[1]

Not wanting to return to Coal Hollow, she enrolled in Chanute Business College. After a year, she took a position in Coffeyville, Kansas, for $8 a week. In 1904, the law office of Veasy & Rowland in Bartlesville, Indian Territory, contacted Chanute Business College looking for a legal stenographer. After interviewing for the position, James A. Veasy and L.A. Rowland, just out of law school, asked her if she would stay until they found someone fitted for the job since she had no legal experience. This was another challenge she met by studying the law and learning what she needed to know to keep the job.

After she married John E. Childers on Aug. 22, 1910, in Bartlesville at the age of 23, she decided to retire from the business world. The Childerses adopted two children, Dorothy and Robert. The Veasy & Rowland firm had difficulty accepting Ms. Childers' retirement, and their daily telephone calls finally convinced her she might as well be drawing a salary because she was still working.[2]

In 1912, Ms. Childers became the law partner of H. H. Montgomery in Bartlesville, and after taking the bar examination and passing with highest honors, she was admitted to the bar between 1912 and 1913. The fact that the Montgomery firm was general counsel for Kanotex would play an important role in Ms. Childers' future.

Ms. Childers and Kittie Sturdevant, another pioneer female attorney, were the only female attendees at the voluntary bar association meeting held in Tulsa in 1914. In 1918, Ms. Childers was an attorney of record in a reported decision dealing with the rights of a Cherokee to make a voluntary alienation of allotted lands.[3]

In 1918, after working for two years under her former boss, Mr. Veasey, who was general counsel for the Carter Oil Co., Ms. Childers joined the Kanotex Oil Co. in Arkansas City, Kansas, as secretary, assistant treasurer and general counsel. She had proven herself in the business world as a "trouble shooter of manifold possibilities in the other business positions she had held"[4] and had a "competent knowledge of nearly every phase of the production, transportation, refining and distribution of petroleum products. She had supervised the construction of pipelines"[5] and "was capable of running the oil through all the operations which make it into gasoline."[6]

In 1919, Ms. Childers went to Devol for Kanotex when the Burkburnett field was coming into its most complete activity. Within one month, in the heart of the oil fields, she counted 25 holdups on the block in front of her office. Although she was never held up, she was threatened many times when she "threatened to put men in jail or send them to the penitentiary for thefts or other crimes."[7]

As Ms. Childers' career was developing at Kanotex, she and C. M. Boggs, president of Kanotex, and Robert R. Cox, treasurer of Kanotex, organized the Crude Oil Transit Co., a pipeline company that transported crude oil to refineries.

An interest aside from the oil industry developed when Ms. Childers became involved in the enactment of Arkansas City's zoning ordinances and became one of the original members of the city planning commission. Her interest in municipal planning was realized with her purchase of the Crestwood District, where she hired authorities to lay out the residential areas. Ms. Childers had streets built, brought in utility service, constructed a community lodge and pool, planted hundreds of trees and installed a nursery to provide for future landscaping. She was also a member of the First Church of Christ Scientist and the Business and Professional Women's Club.

According to Mr. Boggs, Ms. Childers was an amazing woman and a brilliant attorney with a very good business mind.[8] She was not your masculine, heavy-voiced, too-efficient type of woman but seemed to be more at home presiding at a tea table than sitting at a desk directing the destinies of a half-million-dollar business concern.[9] As Ms. Childers stated, "A woman in the business world will be treated simply as she wants to be treated. If she is businesslike, and knows her place and stays in it, the men in her office will treat her in a perfectly friendly, businesslike fashion."[10]

Ms. Childers' advice to women entering the business world was, "Say your prayers and do your best, be honest and work hard ... if you don't want to be criticized, do nothing, say nothing and be nothing."[11]

Ethel Kehrer Childers died June 23, 1946, in Arkansas City.

ENDNOTES

- John S. Boggs Jr.

- Jean Holmes

[1] "From Country Schoolma'm to Oil Magnate," The Kansas City Star, Oct. 4, 1925, p. 10.

[2] Id.

[3] Armstrong v. Goble, 1918 OK 492, 176 P. 530.

[4] "From Country."

[5] "Knowledge of Oil Industry Shaped Woman Lawyer's Career.”

[6] "Mrs. Childers Dies after Long Illness: Kanotex Official One of Midwest's Leading Business Women."

[7] "From Country."

[8] John S. Boggs Jr., email to author.

[9] "From Country."

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

Grace Arnold

Grace Arnold was born in 1888 in Creek County. After passing the bar examination, Ms. Arnold was admitted to the bar in 1915 and began traveling the state of Oklahoma looking for a place to begin her law practice. According to Earl Newsom in Drumright! The Glory Days of a Boom Town, "Fascinated by the oil fields, she came back to Creek County and Drumright on one of the first passenger trains in 1915."[1] She opened her office on the second floor of the J.W. Fulkerson Building, where she practiced until her retirement.

It soon became evident that Ms. Arnold, Drumright's only female attorney, was to be one of Oklahoma's most colorful women leaders. According to Mr. Newsom, "She carried a gun and kept it under her pillow at night.”[2] Disregarding that “proper women” did not smoke in those days, Ms. Arnold did. When preparing for a case, she would lean her forehead on her hands, and the smoke from her cigarettes rose into her snow-white hair, eventually turning it yellow in front.[3] She always wore trousers and could be seen sitting in the movies with her legs draped over the seat in front of her. Although she normally used proper language, if people in the oil field wanted to communicate with her on a “less sophisticated level,” it was said that Ms. Arnold could hold her own.[4]

Underdogs were her favorite clients, and she championed many unpopular causes by representing them in court. In 1917, she joined the International Workers of the World, a group that protested World War I, and over the years, she represented many of its members in court.

Ms. Arnold's court presentations were often very graphic. During a rape case, she once went to the extreme of demonstrating to the court how a woman could resist being attacked.[5] From 1919 to 1956, Ms. Arnold was the attorney of record in 19 reported decisions in Oklahoma. From the day she opened her office in Drumright, she was both respected and accepted in the legal community.[6]

Aside from her legal practice, she was actively involved in politics, taking the stump for Democrats in every election. She was an organizer of the League of Women Voters and the Business and Professional Women's Club in Drumright.

Grace Arnold is buried in the Drumright cemetery.

ENDNOTES

- Earl Newsom

- Scott Pappas

[1] Earl Newsom, Drumright! The Glory Days of a Boom Town, p.61.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Newsom.

[6] Newsom, telephone conversation with author.

Kathryn Nedry Van Leuven

Kathryn Nedry Van Leuven was born Feb. 5, 1888, to John B. and Kathryn Rhyne Nedry in Fort Smith, Arkansas, where she received her primary and secondary education.[1] She moved to Nowata in 1909, where she met her husband, Bert Van Leuven, neighboring Ottawa County's first county judge.[2] A product of six generations of lawyers on both sides of her family, it was only natural that she would be interested in the law.[3] Although she never received a law degree, Ms. Van Leuven was tutored by her husband and father for six years and studied for 18 months at the University of Chicago[4] prior to her admission to the bar in 1913 at the age of 25.[5]

Soon after she began practicing in 1914, Ms. Van Leuven became Nowata County's first female prosecuting attorney when she was named assistant attorney from 1913 to 1915.[6] In 1920, she became the first female assistant attorney general in the U.S. after being appointed to the office by Oklahoma Attorney General S. Price Freeling. Attorney General Freeling, a well-known women's suffrage opponent, had hoped to appease his female critics with the appointment of Ms. Van Leuven,[7] who held the position until 1926.[8]

During her tenure as assistant attorney general, Attorney General Freeling sent Ms. Van Leuven to Tulsa in response to a plea by a delegation of Tulsa women to Gov. Robertson about vice conditions in Tulsa. According to the women, conditions were so bad in their city that it was “unsafe for a woman to travel unescorted.”[9] A. J. Biddison, a Tulsa attorney, believed sending Ms. Van Leuven to Tulsa was a political ploy intended to give her something to do. Of the decision to put Ms. Van Leuven on the case, Mr. Biddison stated that she could “do as little harm [in Tulsa] as she can anywhere else.”[10] Some described the Tulsa assignment as the “most responsible assignment ever entrusted to an Oklahoma woman to that time.”[11] Eventually, Ms. Van Leuven “was credited with breaking up the Tulsa vice ring and soon became Oklahoma's best-known female attorney.”[12] During her six years in the Attorney General's Office, she “was assigned to the Department of Labor where she made an enviable record.”[13]

Having served many challenging years in the public sector, Ms. Van Leuven decided to enter private practice in 1926 when she joined the Oklahoma City law firm of Blakeney & Ambrister. After her son, Kermit, graduated from law school, they formed a mother-son partnership, which was reported to be the first such legal partnership in the nation.[14] Attempting to satisfy her political ambitions, Ms. Van Leuven entered the primary for the U.S. Senate in 1930 and finished seventh in a field of 10 Democratic candidates,[15] an impressive finish for a woman in that era. In 1935, she became a special master to the Supreme Court of Oklahoma and was the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court Commission in Oklahoma.[16]

Beginning in 1924, “Ms. Van Leuven's efforts [became] focused on securing material realization of the program of the National Welfare Committee” when she served on the committee, chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt.[17] The committee compiled and coordinated information, suggesting federal legislation in areas of social security and public welfare. Their suggestions were based on years of work and study by the U.S. Department of Labor, the American Child Health Association, the American Federation of Labor, the National Council of Unemployment, the Department of Vocational Rehabilitation, the Brookings Institution, the American Association of Social Security and others.[18] The work of Ms. Van Leuven and her fellow committee members was “of decided importance in shaping the legislation of the land.”[19]

When the Federal Social Security Board was formed, President and Ms. Roosevelt asked Ms. Van Leuven to become a member of the legal staff. She was appointed to the Social Security Commission in 1937 by President Roosevelt.[20] After a brief tenure on the Federal Social Security Board, Ms. Van Leuven took a leave of absence to accept an appointment by Oklahoma Commissioner of Labor W.A. Pat Murphy to serve as an attorney in the Unemployment Compensation and Placement Division of the Oklahoma Department of Labor.[21] Mr. Murphy was not only impressed with her extensive study of social security but also with her enviable record of legal experience, her position as a national figure and her popularity in Oklahoma. At this juncture in her legal career, an article in the Oklahoma State Bar Journal referred to her as the “first lady of Oklahoma law.”[22]

Ms. Van Leuven became legal advisor, legislative counselor and secretary for the Oklahoma Associated Industries in the early 1940s but resigned in 1945 to become attorney and service director for the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post No. 1857. In 1947, Ms. Van Leuven reentered private practice in Oklahoma City, associating with Judge H. B. King.[23] In private practice, Ms. Van Leuven was a trial lawyer practicing primarily in criminal law. Known for her courtroom advocacy skills, Justice Marian P. Opala remembered her as very tenacious, “as tough a defense lawyer as you could find.”[24] Ms. Van Leuven was an attorney of record in 66 reported decisions from 1919 to 1956.

In addition to being a lawyer, Ms. Van Leuven was actively involved in community and political activities. She was secretary of the State League of Young Democrats, founder and past president of the Young Women's Democrats, member of the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce and founder of the Oklahoma Hospitality Club.[25] Ms. Van Leuven's tremendous involvement in her community, as well as her legal contributions, led to her induction into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1939.[26]

Throughout her life, Ms. Van Leuven was a social activist and championed the rights of her clients and women until her death in December 1967 at the age of 79.[27]

ENDNOTES

- Margaret Dawkins

- Jo Crabtree

- Justice Marian P. Opala

[1] Jean Thomas, “Biographical Sketches,” American Women, March 4, 1939, p. 700.

[2] Orben J. Casey, And Justice For All: The Legal Profession in Oklahoma, 1821-1989, Oklahoma Heritage Assoc., 1989, p. 154.

[3] “Prominent Woman Lawyer Appointed,” Oklahoma State Bar Journal, March 1937.

[4] Casey.

[5] 36 Oklahoma Reports viii, Warden Co., Okla. City, Okla.,1913. Listed on the “Roll of Attorneys” admitted from

June 3, 1912, to Oct. 10, 1913.

[6] Thomas.

[7] Casey.

[8] Patty Grotta “Paving the of Way ... A Look Back at Some Women Who Were Ahead of Their Time – Kathryn Van Leuven,” Briefcase, May 1999, p. 2a.

[9] Casey, p.154-155.

[10] Id. p. 155.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] “Prominent Woman.”

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Thomas.

[17] “Prominent Woman.”

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Grotta.

[21] Casey.

[22] Id.

[23] Grotta.

[24] Justice Marian P. Opala, telephone conversation with author, May 30, 2002.

[25] Thomas.

[26] “Hall of Fame Members Listed,” Oklahoman, Nov. 8, 1987.

[27] Grotta.

Kathryn Sturdevant

Kathryn Sturdevant

Kathryn Clyde "Kittie C." Sturdevant was born Sept. 10, 1890, in Cyclone, Texas,[1] to Charles Wesley and Mary Alice Toole Sturdevant.[2] From the age of 4, she was encouraged by her father, a lawyer, to become a lawyer. He knew the time would "come when women would be more active in business affairs," so they “should all be trained for professional work."[3] After graduating from Shawnee High School in 1908, she went to New York City to become a student at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.[4] Upon returning to Shawnee, she went to work as a stenographer with the law firm of Biggers and Lydick.[5] Mr. Lydick acknowledged her "legal mind" and encouraged her to study law the day she timidly suggested that perhaps he had omitted the jurisdictional statement essential to the petition for an important damage suit.[6] Several Pottawatomie County attorneys also took an interest in her study of the law. Ms. Sturdevant said, "I had the advantage of having several attorneys who were university graduates just to tutor me all the way through until 1912 when I took the (bar) examination."[7] She would later say, "My law school was in the university of hard knocks."[8] In her study of the law under Mr. Lydick, she gained valuable experience in Indian land matters, railroad damage suits and the general practice of law.[9] In addition to her work and study with Mr. Lydick, she also took a correspondence course at the Blackstone Institute in Chicago.[10]

After statehood, the Oklahoma Supreme Court included in the admission requirements that the applicant pass a three-day state bar examination.[11] The final question on the 1912 bar examination was, “Is it lawful for a man to marry his widow's sister?"[12] The lone female applicant in 1912, Ms. Sturdevant responded, "It is unlawful for a marriage relationship to exist between a woman and the ghost of a man."[13] Making the highest grade out of the 125 participants, Ms. Sturdevant was one of the first women in Oklahoma to be admitted to the bar through examination.[14] In prior years, a tradition had been established that the clerk of the Supreme Court would give a choice bird dog to the person attaining the highest grade on the bar examination. When it became known that the highest grade had been made by Ms. Sturdevant, the clerk – who thought a lot of his bird dogs – said he didn't want them to go to anybody who didn't know how to hunt, so according to Ms. Sturdevant, he gave her a check instead.[15]

In 1912, when she was admitted to the bar and began her law practice in Oklahoma City, female lawyers were something of a rarity. The public was not accustomed to female lawyers and doubted that a female was capable of handling legal matters as men did. Some of the judges were also skeptical, and crowds would gather in the courtroom doorway when she tried a case.[16] "At least in the first 20 years, I had to do something much better than a man lawyer would do to get recognition," Ms. Sturdevant once said.[17] Her determination and hard work gained her the respect required to practice law in those days.

Another obstacle presented itself when Ms. Sturdevant was nominated by attorney Edgar A. DeMeules for membership in the voluntary bar association in 1913. Mr. DeMeules concluded his nomination with the following poem:

They talk about a woman's sphere

As though it had a limit:

There's not a place in earth or Heaven,

There's not a task to mankind given,

There's not a blessing or a woe,

There's not a whisper, yes or no,

There's not a life, a death, a birth,

Nor aught that has a feather's weight of worth,

Without a woman in it.[18]

Despite the glowing recommendation, remarks by General Counsel Chairman R. A. Kleinschmidt indicated there was a division in ranks over the question of admitting a woman to the bar. Mr. Kleinschmidt said, "We have taken the precaution to fortify ourselves by securing the signature of at least every well-known admirer of the opposite sex."[19] Mr. W. H. Kornegay then raised the question, "Is she eligible under our constitution?" President James H. Gordon replied, "I am unable to answer that question, for at the time we formed the organization we were not aware we had this danger to confront."[20] G. C. Abernathy of Ms. Sturdevant's hometown of Shawnee moved for her admission. It was seconded, and after a hand vote, Ms. Sturdevant became the association's first woman member[21] and remained an active participant for 75 years.

When she began her practice, Ms. Sturdevant did not specialize in any particular area of law. As she said, "We specialized in anything that came in the front door."[22] She preferred preparing cases and doing research to trying cases in court. When she did go to the courthouses in Wewoka and some of the smaller counties, "the janitors would start cleaning up the courtrooms so they would look neater."[23]

Finally receiving the recognition she deserved due to her hard work, Ms. Sturdevant became president of the Pottawatomie County Bar Association in 1918 and served as secretary and treasurer for 30 years.[24] In 1936, she formed a partnership with Ruby Turner Looper, which "established the first totally female law partnership."[25] Their partnership continued until 1950 when Ms. Sturdevant again became a solo practitioner.[26] During the partnership, Ms. Looper and Ms. Sturdevant were attorneys of record on five reported decisions.[27] Ms. Sturdevant would be an attorney of record on 35 additional reported decisions from 1914 to 1956.

Ms. Sturdevant was instrumental in forming the Lawyers' Tax Group, of which she served as secretary and treasurer for 30 years. She was also active in the Oklahoma Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the Daughters of American Colonists, the Colonial Dames of the 17th Century and the La Petite Soeur Book Club.[28]

At 96, she was still practicing three to four days a week in her downtown Oklahoma City office. When she died on Oct. 24, 1986, she had practiced for 75 years; she had the distinction of being the oldest practicing female attorney in the state.[29] She filed her last pleading, a notice of hearing on the final account in a probate matter, on Feb. 25, 1986.[30] As Stephen P. Friot would say in a Briefcase article paying tribute to Ms. Sturdevant, "She was an inspiration to me. Not only did I see her practice law until she was in her mid-90s, I saw her go about her business with an indomitable spirit."

Ms. Sturdevant was an inspiration to both the legal community and her family. Her great-niece, Susan Huddleston Belote, who was also a lawyer, commented, "A person couldn't have had a better role model in both the law and in life, and we were truly blessed to have this remarkable woman in our family and in our lives."[31]

ENDNOTES

- Susan Huddleston Belote

- Judge Stephen P. Friot

- Patty Grona

- Patty McWilliams

- Justice Marian P. Opala

[1] “Kathryn Clyde (Kittie C.) Sturdevant," The Daily Oklahoman, Oct. 27, 1986.

[2] Joseph B. Thoburn, Muriel H. Wright, Oklahoma: A History of The State and Its People, Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1929, p.37.

[3] Ann DeFrange, "Lawyer is Pioneer in Profession," The Daily Oklahoman, Jan. 21, 1970.

[4] Thoburn.

[5] Bernice McShane, "University of Hard Knocks' Law School in 1912 for Woman Attorney," The Daily

Oklahoman, April 3, 1985.

[6] Orben J. Casey, And Justice For All: The Legal Profession in Oklahoma, 1821-1989, The Oklahoma Heritage

Association, 1989, p.153.

[7] McShane.

[8] Id.

[9] Casey.

[10] The Blackstone Institute, established in 1914, was a self-study two-volume law course for individuals preparing to practice law.

[11] Casey.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] McShane.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Casey.

[19] Id.

[20] Id., p.153-154.

[21] Id., p.154.

[22] McShane.

[23] Id.

[24] “Kathryn Clyde (Kittie C.) Sturdevant."

[25] Patty Grotta, "Paving the Way ... A Look Back at Some Women Who Were Ahead of Their Time: Katherine Clyde Sturdevant,” Briefcase, May 1999, p. 1a.

[26] Id.

[27] Lake, for Use & Benefit of Benton v. Crosser, 1950 OK 49, 216 P.2d 583; Grindstaff v. State, 165 P.2d 846 (Okla. Crim. App. 1946); Burton v. Harn, 1945 OK 29, 156 P.2d 618; State ex rel. Williamson v. State Election Bd., 1943 OK 91, 135 P.2d 982; Hud Oil & Refining Co. v. Smith, 1937 OK 41, 65 P.2d 1011.

[28] “Kathryn Clyde (Kittie C.) Sturdevant."

[29] Grotta.

[30] Stephen P. Friot, "A Tribute to the Human Spirit," Briefcase, October 1991.

[31] Grotta.

Fred Andrews

Fred Andrews, christened Freddie, was born Jan. 14, 1895, in Cecil, Arkansas. When asked if she had been named Freddie because her father wanted a son, she said she "doubted it, for he had plenty of boys, seven girls and six boys."[1] She grew up in Cecil on the family farm and attended Fort Smith Business College.

Ms. Andrews started her career as a legal stenographer in Wetumka. Working in a law firm gave her the opportunity to study law as she worked. She augmented her legal studies with night classes and correspondence courses in law, and after taking the bar examination, she was admitted to the bar on Dec. 13, 1934. She moved to Ada around 1930 and practiced "law in a partnership until 1939, when she opened her own office."[2] She was the first woman attorney in Ada and practiced there for 21 years.

Since there were so few women attorneys when she began her practice, she decided that if she were going to get clients, she would have to use the shortened version of her name.[3] Ms. Andrews tells the story of her first client, a farmer, who purchased a tractor only to find it unsatisfactory. Upon his arrival at the office of “Fred Andrews, Attorney at Law,” the farmer kept insisting he wanted to see a lawyer. When Ms. Andrews finally convinced him she was Fred Andrews, he said, "Well, I better find another, a man. A woman wouldn’t know anything about farm machinery.” She retorted, “No, but I know about contracts."[4] The farmer became a regular client.

Ms. Andrews served as county attorney and, in 1947, served as county judge pro tempore for a brief period of time. She was appointed to the county and juvenile court judgeship in Pontotoc County in 1955 and was unopposed when she ran for election in 1956. During the rest of her 14-year tenure as judge, she would draw an opponent in each election and always come out the victor. She "was the only woman to hold the office of county and juvenile court judge in Pontotoc County."[5] She served "until 1969, at which time she retired and returned to the general practice of law."[6]

A 1957 article in The Daily Oklahoman noted, "Oklahoma women lawyers couldn't be said to dominate the state's judiciary – yet. But keep an eye on them."[7] Ms. Andrews was one of the seven who had made a "wedge into what until very recent times was considered strictly a man's field."[8]

Upon retiring from the judiciary, Ms. Andrews said: "For the most part my work has been pleasant. The last five years, though, the workload has snowballed. With the addition of criminal cases, juvenile and dependent children's cases and mental health matters doubling, there's much more to be done. I'm too compassionate, and tense up trying to find solutions in 'the best interest' of the child or adult."[9]

Although Ms. Andrews never felt the legal profession called "for exceptional qualities in a woman any more than it does a man," she did question the ability of women to deal with "dependent and neglected or delinquent children."[10] Although she had her doubts about her abilities in these areas, she felt she had helped a number of young people, a fact confirmed by the many who kept in touch with her throughout her life.

Retiring to a private practice, Ms. Andrews hoped to return to a 9-to-5 workday. She anticipated that private practice would allow her more time to work in her yard with her flowers, a diversion she thoroughly enjoyed. She opened her office in Ada's First National Bank in a space offered by Albert E. Trice. Returning to the areas of practice she enjoyed before she became a judge, she opened her doors to a civil practice focusing on probate matters.

Never marrying, Ms. Andrews "made her way through the difficult times of the Great Depression and raised her deceased sister's children, Norma Wood Smith and James 'Jimmie' Smith."[11]

A "doer, not a spectator," Ms. Andrews was active in community affairs.[12] She was a charter member of the Business and Professional Women's Association and served as president of the Wetumka chapter and legislative chairman and parliamentarian of the state organization. She was a recipient of the Ema Warmac trophy for being the outstanding member of the Ada Business and Professional Women's Association. She also served as president of the Knife and Fork Club and the Ada Community Chest in 1961. She was a member of the Order of the Eastern Star and was on the Board of Directors of Valley View Hospital. She worked as a volunteer for the American Cancer Society from 1955 to 1959 and remained an active member thereafter. She was county director of the American Red Cross and was on the sanitation board, working in conjunction with the health department.

She was a member of the Pontotoc County and Oklahoma bar associations and also spent a great deal of time promoting the Women Lawyers Club, which became the Oklahoma Association of Women Lawyers.

Awards, citations and plaques noting her many accomplishments lined the walls of her Ada office. As noted by fellow attorney Bob E. Bennett of Ada, Ms. Andrews was "highly respected and admired by all who knew her. She was a dedicated member of the bench and bar ... a tribute to our profession."[13]

Fred Andrews died in October 1977 at the age of 82.

ENDNOTES

- Bob E. Bennett

- Jean Holmes

[1] Wenonah Rutherford, "Judge Andrews Returning to Private Practice Here," Ada Sunday News.

[2] Georgia Nelson, "Women Reign as Justices," The Daily Oklahoman, Oct. 13, 1957.

[3] Rutherford.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Bob E. Bennett letter to author, May 29, 2002.

[7] Nelson.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Bennett.

[12] Rutherford.

[13] Bennett.

Norma Frazier Wheaton

Norma Frazier Wheaton was born Aug. 13, 1899, in New York City and was orphaned at the age of 11. The oldest of three children, Ms. Wheaton became a parent to her younger siblings. After graduating from Northwestern University, she took a secretarial position in the office of Hudson and Hudson, a Tulsa law firm, so her siblings could also receive a college education.[1]

While working for Robert D. Hudson and his father, Wash Hudson, Ms. Wheaton realized she wanted her legal career to involve more than just typing briefs for the Hudsons. She wanted to be a lawyer. Determined, she entered the TU College of Law and graduated with highest honors in 1927.[2] She was admitted to the Oklahoma bar later that year. After graduating, Ms. Wheaton continued her career with Hudson and Hudson but traded her secretarial duties for those of an attorney. In 1947, she was named a partner in the firm, which became Hudson, Hudson, Wheaton and Brett.[3]