Oklahoma Bar Journal

General Corporate Due Diligence in Mergers and Acquisitions Transactions

By Tiantian Chen

David | #517234137 | stock.adobe.com

It is common knowledge that legal due diligence is a critical step in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions. This article, intended as a quick reference for junior M&A attorneys tasked with the legal due diligence process, includes certain basic discussions of the most common legal diligence issues.

For simplicity purposes, the discussions in this article are limited as follows: 1) this article does not address the business, financial or other types of nonlegal diligence that may occur in connection with M&A transactions; 2) this article focuses on the legal due diligence performed after the execution of the letter of intent (LOI) and does not include discussions of the preliminary diligence performed before an LOI; 3) the discussions are centered on a simple transaction with only one acquiring entity (the buyer) and one selling entity (the seller), without any lenders or financing sources, representations and warranties insurance providers and other third parties; 4) the discussions are further limited to the review of the due diligence files provided by the seller and do not extend to any required legal research; and 5) the discussions are focused on the typical legal diligence performed by the general corporate team, and it does not involve discussions of any specialty diligence that are usually performed by specialists in applicable areas of law, e.g., securities regulations, labor and employment, employee benefits, environmental regulations, healthcare regulations, data privacy, intellectual property, real estate, government contracting, etc. Additionally, this article only focuses on some of the most typical corporate legal diligence issues and does not include exhaustive discussions of all potential legal diligence issues.

The analysis and information included in this article are for general informational purposes only. Nothing herein constitutes, or is intended to constitute, legal advice. No attorney-client relationship is created between the reader and the author. The author expressly disclaims any liability with respect to any actions that a reader may take based on the analysis in this article. The analysis in this article is presented “as is,” and the author makes no representation that the content herein is error-free.

GENERAL

Review the LOI

The legal due diligence process frequently starts promptly or soon after the execution of an LOI, and the LOI may contemplate the expected completion date of the legal due diligence process. Failure to complete the legal due diligence within the agreed timeline could result in serious consequences, such as the expiration of the exclusivity period agreed to between the buyer and the seller in the LOI.

It is strongly recommended that all members of the legal diligence team review the LOI before beginning the legal due diligence review in order to 1) understand the deal structure and identify the key diligence issues accordingly and 2) control their diligence progress to ensure timely completion of the diligence process.

The Role of the Corporate Team

The general corporate team serves a role akin to a “control center” in a legal due diligence process. The corporate team is usually the first among the entire transaction team to have direct coordination with the client regarding the client’s diligence needs and concerns, and it is the corporate team’s responsibility to recommend and bring in the proper legal specialists to assist with the diligence process. The legal specialists rely on the general corporate team to introduce them to the client, gain access to the virtual data room (VDR), where the diligence files are uploaded, and forward relevant diligence files or information to the extent such files or information are not properly uploaded to the VDR. The corporate team should inform the legal specialists of the diligence timeline as soon as possible and track the legal specialists’ diligence progress. As the specialists proceed with their diligence review, the corporate team is expected to consolidate and pass along the specialists’ supplemental diligence requests, comments and recommendations and arrange direct discussions between the client or the counterparty and the applicable specialists as necessary. If a diligence memorandum is required, the corporate team is responsible for collecting all diligence summaries from the specialists and incorporating them properly into the final memorandum.

In addition to generally coordinating the communication between the client, the counterparty and the legal specialists, the corporate team is also expected to perform the typical “corporate diligence,” which typically includes the review and analysis of the general corporate and securities records, liens and litigation records and commercial contracts. These subjects are discussed further below.

What To Look For and Why

The key to successful diligence is to understand what we are looking for, and the answer to that further requires us to understand why we are looking for certain information. Even though the buyer’s counsel and the seller’s counsel are reviewing the same documents, the buyer diligence and the seller diligence serve slightly different purposes. From the buyer’s perspective, the primary concern is identifying any potential risks the buyer may be exposed to post-closing; in a strategic transaction, the buyer is also concerned with successfully integrating the seller’s business resources into the buyer’s business structure post-closing. From the seller’s perspective, the primary goal of the legal due diligence is to ensure proper and sufficient disclosure to avoid potential breaches of its representations and warranties under the purchase agreement, as well as the proper performance of any required pre-closing actions, such as obtaining any necessary third-party consents for the transaction.

When making the diligence protocol, the seller counsel should at least look for the typical red flags that are often expected to be covered under a disclosure schedule. If a draft purchase agreement is available before the diligence starts, the seller diligence team is recommended to review the draft purchase agreement first, particularly the representations and warranties provisions, to make sure its review covers at least the particular items explicitly required by any disclosure schedule, e.g., commercial contracts with noncompete covenants, pending litigations, etc.

As for the buyer team, its review protocol should include not only the items that need to be disclosed under the purchase agreement but all other issues the client would want to know given its business needs. For example, if the buyer intends to lay off a certain key employee of the seller’s business post-closing, the buyer diligence team should not only review such employee’s employment agreement to identify potential legal risks associated with such planned layoff but also look out for material commercial contracts where such employee is currently designated as a point of contact (POC) and where a change in the POC designation requires the counterparty’s prior consent.

TYPICAL CORPORATE LEGAL DILIGENCE ISSUES

As mentioned above, the general corporate team is not only expected to serve as the “control center” in the legal diligence process but also to perform the typical corporate diligence. The following sections relate to certain typical subjects in general corporate diligence.

General Corporate and Securities Documents

This group of documents generally includes all documents related to the formation and governance of the seller’s business, as well as issuance of the company’s equity which, depending on the form of business entity (e.g., corporation, general partnership, limited partnership, limited liability company, etc.), typically includes the articles of incorporation, certificate of formation, bylaws, stockholders agreements, limited liability company agreements or operating agreements, limited partnership agreements, incentive stock option plans, options, warrants, stockholder resolutions and consents, Board of Directors resolutions and consents, board of managers resolutions and consents, foreign qualification records and other similar instruments. Diligence teams for both the buyer and the seller need to carefully review these documents to understand the target company’s history, management structure and capitalization, which typically include the following issues:

Organization. Typically, the first representation the seller needs to provide in a purchase agreement is that its business entity is duly organized, validly existing and in good standing. Verifying such representation requires careful review of the seller’s formation and governing documents, including any amendments thereto, where the diligence team should look out for the seller’s date and state of organization, entity type, whether the seller has changed its name, state of organization, whether it has converted into a different type of business entity, merged into or with another entity, whether the seller has any subsidiaries and affiliates, whether the seller is in good standing in its state of organization and each jurisdiction where it is qualified to transact business, etc.

Capitalization. In any equity transaction, one of the most important representations made by the seller is the proper issuance and ownership of its equities. The diligence team should carefully review the seller’s formation and governing documents, including any equity issuance documents and the capitalization table, to determine the total amount of authorized securities of the company; whether such authorized amount has been adjusted; whether any new categories or classes of securities have been authorized and issued; the current equity holders that own the company’s equities; anyone who holds an option, warrant, convertible note or other right to acquire the company’s equities in the future; whether all the issued and outstanding equities have been properly authorized; whether any equity holders’ equities have been redeemed or repurchased; which classes of equities are voting equities and which are nonvoting equities; etc.

Transaction authority. Both the buyer and the seller diligence teams should carefully review the seller’s corporate governance documents to determine the proper corporate resolution or consent required to approve the underlying transaction. For example, the seller’s bylaws may require approval by the Board of Directors, while the seller’s articles of incorporation may also require approval by most of its voting stockholders. If so, resolutions or written consent should be obtained from both the board and the voting stockholders to ensure that the transaction is properly authorized. Because the seller’s corporate governance documents may or may not be properly drafted or updated, the diligence team should also perform proper state law review and analysis to ensure the level of consent required for the contemplated transaction.

Foreign qualifications. Frequently, a seller may conduct business in multiple jurisdictions, including other countries, and both the buyer and the seller should ensure that the seller is properly qualified to transact business in all such jurisdictions where its business operations require so. To the extent the seller is qualified in foreign jurisdictions, the diligence team should also review the seller’s qualification records and ensure it is in good standing in each such jurisdiction. For example, if the seller's qualification in a foreign jurisdiction is revoked due to its failure to file required annual reports, remedial actions should be taken promptly, and proper disclosures should be made under the purchase agreement.

Commercial Contracts

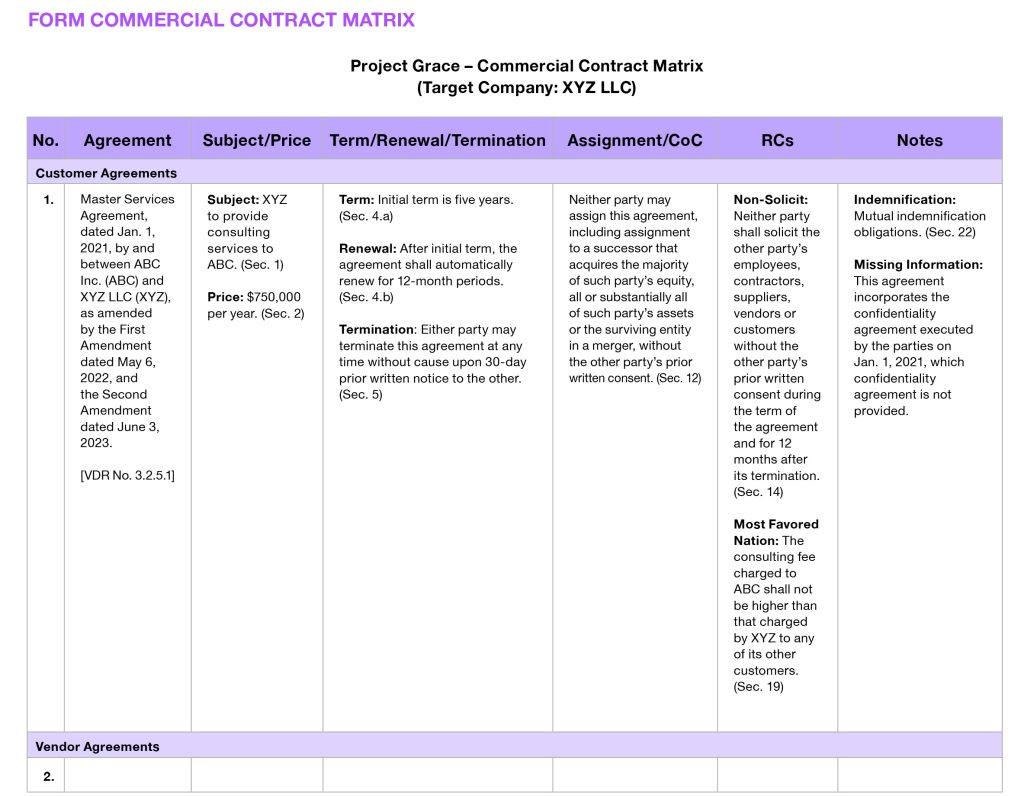

Due diligence review of the seller’s commercial contracts is usually the most time-consuming part of the diligence process. The diligence team should carefully design a summary table (which is frequently called a matrix) so that each contract is properly summarized based on the key diligence issues. A sample commercial contract matrix is included at the end of the article. Certain key contract issues are discussed below. To avoid confusion, the underlying purchase agreement in the contemplated M&A transaction is referred hereto as “purchase agreement,” whereas “contract” refers to the seller’s commercial contract subject to diligence review.

Contract description. Each contract should be properly described so that it can later be properly cited. Typically, a contract should be described by its title, date and contracting party in the form of “[CONTRACT TITLE], dated [DATE], by and between [PARTIES].” If a contract has been amended, the amendments should also be referenced in the description of the contract, e.g., Master Services Agreement, dated Jan. 1, 2021, by and between ABC Inc. and XYZ LLC, as amended by the First Amendment dated May 6, 2022, and the Second Amendment dated June 3, 2023. In addition to the official description of the contract, the diligence team should also note the contract’s file name and VDR number (if any) so that the diligence team can easily find the particular document in the VDR if it needs to.

Service and product; contract amount. Sometimes, it is not easy to perceive the service or product being provided under a contract solely by the contract title. Additionally, whether a contract needs to be disclosed under the purchase agreement frequently depends on whether the contract amount meets the required disclosure threshold. Therefore, the diligence team should also include a brief description of the subject matter and the amount of fees under a contract in its summary. If there are any special payment arrangements between the seller and the counterparty under the contract, such as any sort of profit-sharing, such payment terms should also be noted.

Drobot Dean | #207740290 | stock.adobe.com

Term, renewal and termination. For both disclosure purposes and business integration purposes, it is important for the diligence team to understand whether a contract is still in effect and the circumstances under which it can be terminated. In addition to a contract’s initial term, the diligence team should note the options, if any, for the initial contract term to renew, e.g., a contract may be renewed only by mutual consent from both contracting parties, or a contract may automatically renew unless notice not to renew is provided by either party during a certain period of time before the next renewal date, or a party may have been given a set number of renewal options that such party may unilaterally exercise during a certain period of time before the contract expiration date. With respect to the circumstances under which a contract may terminate, depending on the client’s particular needs, a termination for convenience is usually the primary concern for the diligence team. In some cases, the buyer may prefer a contract where it may terminate at any time without cause, whereas in others, it may be reluctant to assume a contract that can be terminated by the counterparty for convenience. If termination for convenience would result in any early termination fee or penalty, the diligence team should also include such information in its summary.

Assignment or change of control. Assignment or change of control (CoC) restriction is one of the most important contract diligence issues. Failure to obtain proper consent from third parties could have a serious impact on the transaction. Depending on the transaction structure, the diligence team usually looks for either assignment restrictions or CoC restrictions. However, in the uncommon situation where a transaction structure has not been finalized or where a transaction involves multiple structures, the diligence team may want to look out for both issues in its review. Additionally, the diligence team should look out for any contract provisions where an “assignment” is broadly defined to include a CoC event, in which situation any restrictions applicable to assignment would also apply to a CoC. In respect of CoC, depending on the transaction structure, the diligence team is also recommended to flag any “indirect” CoC restriction, where restrictions are triggered by the CoC event in a parent entity or other affiliates of the seller.

“Restrictions” come in many forms, and the diligence team should look out for all, e.g., whether a contract requires the counterparty’s prior (written) consent before the seller assigns the contract to the buyer or goes through a CoC event, whether an assignment or CoC constitutes an event of default, whether the contract requires the seller to provide assignment or CoC notice letter within a certain period of time before closing, whether the seller is required to provide particular types of documents – such as the buyer’s financial records – when seeking the counterparty’s consent, whether the seller is required to pay any penalty or whether the counterparty is granted any right to terminate the contract in the event of an assignment or CoC, etc.

Certain restrictions can be so significant that once seen, should be immediately flagged to the entire deal team and the client. For example, if the LOI contemplates a 45-day diligence timeline whereas a contract requires a 90-day prior notice to the counterparty in an event of assignment or CoC, the transaction parties may have to exclude such contract from the transaction. Occasionally, the counterparty may even have been granted a right of first refusal or similar right where it has the right to acquire the seller’s business before anyone else, in which situation the buyer may decide to abort the transaction entirely.

Notable restrictive covenants. If a contract includes notable restrictive covenants, such restrictive covenants may have a serious impact on the buyer’s business post-closing. Therefore, almost all M&A purchase agreements require disclosure of notable restrictive covenants, including by example: noncompete covenants, where the seller or the seller’s successor is prohibited from engaging in a certain line of business; non-solicitation covenants, where the seller or the seller’s successor is prohibited from soliciting the counterparty’s employees, contractors, customers, vendors, suppliers or other business relationships; exclusivity covenants, where the seller or the seller’s successor is required to deal with the counterparty exclusively for the service or product provided under the contract; most-favored-nation clauses, where the seller or the seller’s successor is required to offer the counterparty the best pricing or other terms compared to all other customers of the seller or its successor; minimum quantity or requirements contracts, where the seller or its successor is required to purchase a certain minimum quantity of products or services or purchase its entire need for such products or services from the counterparty; etc.

Other notable items. Occasionally, a contract may incorporate governing terms and conditions available on a party’s website, in which case the diligence team should follow the proper link and review such online terms and conditions. While certain contract provisions may not be subject to disclosure requirements under the purchase agreement as frequently as the other notable restrictive covenants, they may, nevertheless, have an important impact on the buyer’s business post-closing. Depending on the client’s business needs and transaction budget, the diligence team may also want to include them in its summary, e.g., whether the seller owes any indemnification obligations to the counterparty, the seller’s liability is capped to a certain amount, the contract provides for mandatory arbitration, etc. Additionally, the diligence team should also note any missing items as it proceeds with the diligence review. For example, if a purchase order incorporates a master agreement by reference but such master agreement has not been uploaded to the VDR, the diligence team should note a supplemental diligence request for such master agreement.

Liens and Litigation Records

Liens. Obviously, the buyer does not wish to acquire a business whose assets and equities have been encumbered with liens in favor of third parties. Therefore, it is imperative for the diligence team to identify if any lien on the seller's assets and properties exists, and with very limited exceptions, the buyer typically requires all such liens to be terminated before closing.

To properly identify any potential liens, the buyer (and not infrequently the seller) would perform lien searches over the seller’s business, which are performed based on the seller’s business name(s) and location(s). That is why it is critical for the diligence team to identify any “doing business as” (DBA) names or former names of the seller based on its corporate records and the seller’s state of organization, principal business office and all other office locations. Depending on the specific situation, the lien search may be limited to the seller’s official business name and its state of organization. However, frequently the lien search also expands to the seller’s DBA names and former names and all countries, states and counties where the seller has any physical location or conducts any business.

The primary source of liens and encumbrances under the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) typically comes from the seller’s financing agreements and capital leases. For the indebtedness and liens the parties intend to terminate before closing, the diligence team should particularly look out for prepayment options and penalties. For the indebtedness and liens the parties intend to continue post-closing, which typically includes capital leases, the diligence team should look out for all red flags in the same way it reviews other commercial contracts.

Normally, the lien search result should match the debt records provided by the seller. However, mismatches may happen under various circumstances, and the diligence team needs to look out for such mismatches. For example, the lien search report may reference certain capital leases or financing agreements the seller omitted to provide, in which case the diligence team should add supplemental diligence requests accordingly. Also, even under a normal commercial contract, the counterparty may be granted a security interest in the seller’s assets, whether or not a UCC financing statement has been filed. In such a situation, such security interest should be disclosed and flagged, even though it is not included in any lien search report.

Litigation. Any litigation or adverse action involving the seller is a red flag to the buyer. A typical lien search includes searches of litigation records as well. Whether or not a litigation is closed, the diligence team should review the key diligence records – e.g., the complaint, the answer, any settlement agreement and any key judgment issued by the court – to determine whether the buyer is at any risk of exposure to such litigation if the transaction closes. If there is any ongoing litigation or adverse action involving the seller, the diligence team should actively track the litigation process and provide corresponding risk mitigation strategies accordingly. If any litigation is being threatened against the seller, the diligence team should thoroughly understand the circumstances that may lead to future litigation and take necessary remedial actions as early as possible.

SUMMARY

At the end of the day, there is not one legal due diligence plan that suits all M&A transactions. The scope and the depth of the legal due diligence process depends on the structure of the transaction, the industry of the transaction parties and the particular areas of concern for all parties involved. It is imperative for transaction attorneys to understand their client’s business and legal needs before designing a diligence plan with the proper level of complexity and coverage.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tiantian Chen is an associate at Hartzog Conger Cason. Her practices focus on mergers and acquisitions and private equity transactions. Ms. Chen practices in Texas only and is not licensed in Oklahoma.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 95 Vol 7 (September 2023)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.