Oklahoma Bar Journal

Carpenter V. Murphy: Will the U.S. Supreme Court Recognize the Continued Existence of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's Reservation?

By William R. Norman

© Sergey Kamshylin | #50486766 | stock.adobe.com

Before the United States Supreme Court is a case that could drastically affect tribes’ jurisdiction in Oklahoma. If the Indian defendant and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation (Creek Nation) are successful, Carpenter v. Murphy would reverse the state of Oklahoma’s long-standing assumption that reservation boundaries located within its borders no longer exist.

Although the jurisprudence governing reservation status is well-settled – requiring clear congressional intent to disestablish a reservation and utilizing a three-factor test to assess whether that intent exists – Oklahoma seeks to turn this analysis on its head in order to maintain its posture that Oklahoma is reservation-less, despite being home to 38 federally recognized tribes. Oklahoma’s position has had very real consequences for tribes located in Oklahoma – many of which have already suffered the devastating impacts of removal from their homelands. Oklahoma’s stance not only supports its assertion of jurisdiction over crimes Congress has clearly said it does not have, but it also strips tribes of the jurisdiction they possess as an aspect of their inherent sovereignty over their reservation lands. The outcome in Murphy will either redress this wrong or further it (at least for the Creek Nation).

LAWS REGARDING JURISDICTION AND RESERVATION DISESTABLISHMENT ARE WELL SETTLED

While questions of jurisdiction on tribal land are often complicated, it is clear and well-settled law that the federal government, to the exclusion of states, has jurisdiction over murders committed by Indians in Indian country.1 The Major Crimes Act, originally enacted in 1885, currently reads as follows:

Any Indian who commits against the person or property of another Indian or other person any of the following offenses, namely, murder … within the Indian country, shall be subject to the same law and penalties as all other persons committing any of the above offenses, within the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States.2

Indian country, in turn, is defined to include:

(a) all land within the limits of any Indian reservation under the jurisdiction of the United States Government, notwithstanding the issuance of any patent, and, including rights-of-way running through the reservation,

(b) all dependent Indian communities within the borders of the United States whether within the original or subsequently acquired territory thereof, and whether within or without the limits of a state, and

(c) all Indian allotments, the Indian titles to which have not been extinguished, including rights-of-way running through the same.3

Thus, when an Indian commits murder within the boundaries of a reservation, a state court does not have jurisdiction over prosecution of the crime.

The Supreme Court has affirmed that the Major Crimes Act applies to crimes committed within the boundaries of reservations regardless of the ownership of the particular parcel of land on which the crime was committed,4 and formal designation as a reservation is not required.5

It is also well settled that a tribe’s reservation boundaries remain intact unless Congress explicitly disestablishes or diminishes them. In one of the harshest decisions affecting tribes, Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, the Supreme Court said Congress has the power to unilaterally abrogate treaties made with tribes,6 later clarifying this includes the power to eliminate or reduce tribes’ reservation boundaries.7 The Supreme Court has taken pains to emphasize congressional intent to disestablish or diminish a reservation must be “clear and plain,” with ambiguities resolved in favor of tribes.8 In this vein, the Supreme Court has said that the allotment of land within a reservation does not itself disestablish the reservation.9

The Supreme Court has developed and repeatedly applied an analysis it refers to as the three-part Solem test to determine whether congressional intent exists to disestablish or diminish a reservation. Specifically, the Solem test looks to the following three factors, ranked from most to least weighty, to discern congressional intent:

1) The text of the statute purportedly disestablishing or diminishing a reservation, especially whether there are references to cessation, total surrender of all interests of the tribe, unconditional commitment for a specific sum of compensation for the land or restoring land to the public domain;

2) Events surrounding passage of the statute that unequivocally reveal a widely held and contemporaneous understanding that the affected reservation would be reduced as a result of the legislation; and

3) Events that occurred after passage of the statute, including Congress’s treatment of the area, the way the Bureau of Indian Affairs and local judicial authorities treated the area, and who actually moved onto the opened land, where this evidence reinforces a finding under the other factors (it cannot alone establish disestablishment or diminishment).10

The continuing vitality of this test was reaffirmed by a unanimous Supreme Court in 2016 in Nebraska v. Parker.11

THE UNJUST HISTORY OF THE MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATION

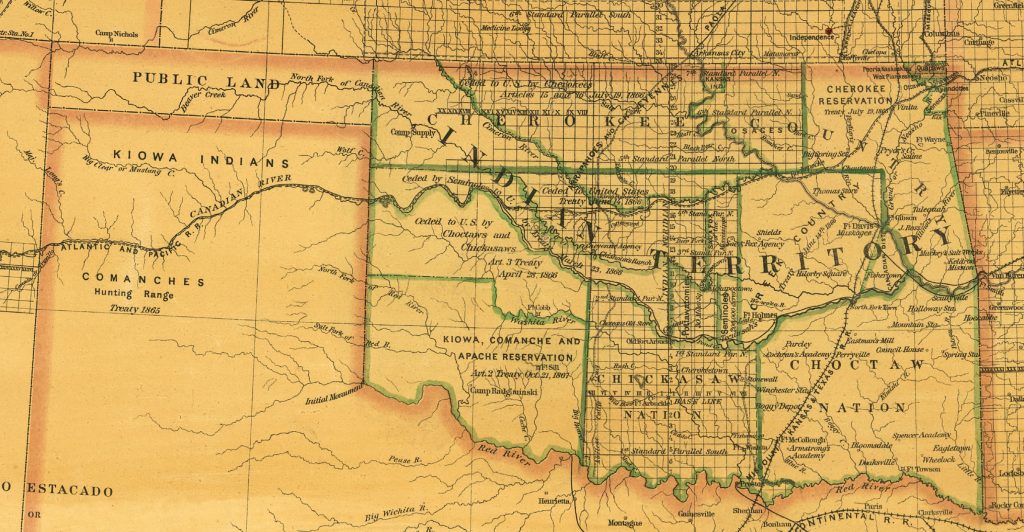

The Creek Nation’s homelands were located in the southeastern United States, but it was forcibly removed in the 1820s by the United States to land west of the Mississippi River in what is today Oklahoma.12 The United States undertook the Creek Nation’s removal and relocation through a series of treaties. Even once removed from its homelands, in 1856 and 1866 the Creek Nation was pressured into treaties that diminished the size of its reservation in Oklahoma (hereinafter the Creek Reservation).

Due to increased westward expansion by white settlers, in 1893, Congress created the Dawes Commission to negotiate with the Creek Nation (as part of the Five Civilized Tribes) for the allotment of its land. When the Creek Nation resisted, Congress took actions to restrict the jurisdictional and other governmental powers of its government. Finally, after mounting pressure, in 1901, the Creek Nation agreed to allotment and Congress enacted the agreement into law – which called for elimination of the Creek Nation’s government by March 4, 1906.13 When it became clear that the deadline would not be met, Congress enacted the Five Tribes Act,14 which delayed plans to terminate the Creek Nation’s government. In 1906, Congress also passed the Oklahoma Enabling Act,15 which allowed the Territory of Oklahoma, together with Indian Territory, to apply for statehood – paving the way for creation of the state of Oklahoma.

Remarkably, Oklahoma thereafter asserted that the reservations in Oklahoma ceased to exist – including the Creek Reservation. For the most part, the federal government allowed Oklahoma to continue under this faulty assumption without consequence. Because the extent of a tribe’s governmental authority or jurisdiction to govern, care and provide for its people is often tied to its geographic boundaries, the existence and extent of those boundaries is critical to the tribe. The outer boundaries of tribes’ reservations provide them governmental jurisdiction over their territorial land base – much like a state’s jurisdiction within its borders. Oklahoma’s assumption against reservation existence has created near continual friction between Oklahoma and tribes over the tribes’ sovereign governmental powers.16

MR. MURPHY’S CASE

The case at hand, Carpenter v. Murphy, arises from the alleged 1999 murder of George Jacobs by Patrick Murphy – both citizens of the Creek Nation – in Henryetta on a roadside in a rural area. Although this is a murder prosecution at heart, these underlying facts are not often discussed, eclipsed by the case’s potential jurisdictional impacts.

Mr. Murphy was prosecuted in an Oklahoma court, where, in the year 2000, a jury convicted him of murder and he was sentenced to death. Mr. Murphy filed an application for post-conviction relief alleging Oklahoma lacked jurisdiction because the Major Crimes Act gives the federal government exclusive jurisdiction to prosecute murders committed by Indians in Indian country. After the Oklahoma court ruled against him, Mr. Murphy included this claim in a federal habeas application, eventually appealing to the United States Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit.

In 2017, the 10th Circuit concluded that although it owed deference to the Oklahoma court’s determination that it had jurisdiction, in not applying the Solem test, the Oklahoma court had “applied a rule that was contrary to clearly established Supreme Court law” and the 10th Circuit “must apply the correct law.”17 The 10th Circuit examined the three factors laid out in the Solem test and found the Creek Reservation had not been disestablished, explaining:

The most important evidence – the statutory text – fails to reveal disestablishment at step one. Instead, the relevant statutes contain language affirmatively recognizing the Creek Nation’s borders. The evidence of contemporaneous understanding and later history, which we consider at steps two and three, is mixed and falls far short of “unequivocally reveal[ing]” a congressional intent to disestablish.18

Oklahoma, thereafter, requested the United States Supreme Court grant its petition for certiorari and review the case, focusing on the question of whether the Creek Reservation had been disestablished. In a surprising move to many, the Supreme Court granted review of the case19 and, on Nov. 27, 2018, heard oral arguments. Many amicus briefs were filed due to the potentially broad impacts of the case.

OKLAHOMA’S ARGUMENTS SUPPORTED BY DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

Oklahoma argued that the Creek Reservation did not survive Congress’ allotment of the land and purported “dismantlement” of the Creek Nation’s sovereignty leading up to creation of the state of Oklahoma, claiming these actions are incompatible with reservation status.20 The United States through the Department of Justice (DOJ) – the trustee owing a legal fiduciary responsibility to tribes under federal law – echoed, via amicus, this argument. According to DOJ, in preparation for creating the state of Oklahoma, Congress disestablished the Creek Reservation through a series of statutes that broke up the Creek Nation’s land, including through allotment, limited its governmental authority, applied federal and state law to Indians and non-Indians on the land and set a timetable for dissolution of the Creek Nation.21 DOJ said Oklahoma is unique from other states (whose formation did not disestablish reservations within their borders) because, according to DOJ, turning Oklahoma into a state was accomplished in part by replacing the tribes’ governments with Oklahoma’s government and disestablishing the tribes’ territories in order to shift their territorial domain to Oklahoma.22

Oklahoma and DOJ emphasized stereotypical views of, as DOJ put it, “weaknesses in the Indian governments.”23 They used these stereotypes to support their assertions that Congress was unhappy with tribes’ exercise of jurisdiction leading up to creation of the state of Oklahoma, alluding to harm that would result from a finding that the Creek Reservation’s boundaries still remain intact.

Oklahoma and DOJ also claimed that Oklahoma’s exercise of jurisdiction over the land evidences the Creek Reservation’s disestablishment, with DOJ stating:

For nearly a century, both Oklahoma and the United States have treated the statehood-era statutes as having disestablished the Creek Nation’s former domain: the State has exercised criminal jurisdiction over offenses committed by Indians on unrestricted fee lands within the Creek Nation’s former territory, while the United States has not attempted to exercise such jurisdiction.24

To support their claims of consequences that would follow from finding the Creek Reservation still exists, they said convictions under Oklahoma jurisdiction would be called into question, and DOJ said the requirement that the federal government, rather than Oklahoma, exercise criminal jurisdiction would be too large a burden.25

ASSERTIONS THE CREEK RESERVATION REMAINS INTACT

Mr. Murphy, and the Creek Nation as amicus, supported by the thorough and well-reasoned 10th Circuit decision below, argued that the Creek Reservation was never disestablished but, instead, remains intact today.26

As discussed previously, the Supreme Court’s test for determining whether a reservation has been disestablished looks for clear congressional intent, evidenced by statutory text first and foremost. During oral arguments, Justice Kagan repeatedly described the test as examining whether a congressional act disestablished a reservation and nothing else.27

Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation demonstrated that language disestablishing the Creek Reservation is lacking in the text of any statute.28 Neither Oklahoma nor DOJ contended otherwise. In fact, the 10th Circuit examined each of the eight statutes Oklahoma identified as together establishing congressional intent to disestablish the Creek Reservation, finding that none contained textual language demonstrating such intent, but rather that their language indicated just the opposite: Congress continued to recognize the Creek Reservation.29

Moreover, although not necessary to find a reservation was not disestablished, the 10th Circuit decision cited cases supporting the continued existence of the Creek Reservation.30 Most notably, in 1987, the 10th Circuit found the Creek Reservation still exists but reserved the question regarding whether its 1866 boundaries remained intact.31

Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation also demonstrated, and the 10th Circuit below agreed, that Oklahoma’s and DOJ’s arguments regarding congressional acts to restrict the Creek Nation’s governmental power, including over its land, are not relevant, including those meant: 1) to shift ownership of particular parcels of land away from the Creek Nation through allotment; and 2) to “dissolve” the Creek Nation’s government.32 Rather, all that matters in the analysis is whether a congressional act disestablished the reservation. Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation asserted further that, as previously noted, the Supreme Court has expressly said reservation boundaries continue to exist despite allotment.33 Additionally, Justice Breyer noted during oral arguments, many statutes limit tribes’ jurisdictional authority over their reservation land (and sometimes even grant the state jurisdiction) without disestablishing the reservation.34

However, even if it were relevant, as established by Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation, the Creek Nation continues to exist and exercise authority over the Creek Reservation. As the 10th Circuit recognized, congressional consideration of “dissolving” the Creek Nation’s government never led to actual dissolution, but rather the Creek Nation continues on as a strong government with a vibrant community.35

Similarly, Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation contended that creation of the state of Oklahoma did not disestablish the Creek Reservation. Instead, as they and the 10th Circuit noted,36 Congress, in the Oklahoma Enabling Act, imposed restrictions on the new state of Oklahoma’s ability to affect tribes’ property,37 and Oklahoma disclaimed title and jurisdiction at the time of statehood.38 In fact, the 10th Circuit determined that no precedent supports the claim that creation of the state of Oklahoma in any way served as congressional intent to disestablish the Creek Reservation.39 Instead, as Mr. Murphy pointed out, other states, when admitted to the Union, contained a significant percentage of reservation land, and yet those reservations were not disestablished.40

In response to arguments that practical consequences would be too great, Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation reminded the court that practical consequences are not relevant to a reservation disestablishment analysis41 but, they said, even if they were significant, the practical consequences of a finding that the Creek Reservation still exists are not as significant as some would make them out to be.

First, as both Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation noted, a court may find that a tribe no longer possesses sovereignty over reservation land even though the reservation boundaries continue to exist.42 Additionally, they both noted, tribes’ jurisdiction, especially over noncitizens, even on reservation land, is seriously limited by Supreme Court precedent.43

Second, Mr. Murphy and the Creek Nation established, as previously discussed, the Creek Nation has been exercising jurisdiction over the Creek Reservation throughout time. Specifically, the Creek Nation demonstrated that it provides critical services to citizens and noncitizens alike throughout the Creek Reservation, including services related to health care and education as well as law enforcement and domestic violence.44 Evidencing the importance of the Creek Nation to the safety and well-being of all persons throughout the Creek Reservation, its police department has entered into cross-deputization agreements with the United States, Oklahoma and 32 county and municipal jurisdictions, including the city of Tulsa. As the 10th Circuit had noted, there existed a continuous governmental presence of the Creek Nation on the Creek Reservation, and many of the powers Congress temporarily restricted through the allotment statutes were later restored.

Lastly, while it may be true that Oklahoma has been exercising jurisdiction (arguably unlawfully) over the Creek Reservation for many years, the 10th Circuit rightly stated that “Oklahoma’s exercise of jurisdiction within the Creek Reservation is not a proper basis for us to conclude that Congress disestablished the Reservation.”45 Similarly, while there is a large non-Indian population living within the boundaries of the Creek Reservation, the 10th Circuit found controlling Nebraska v. Parker, where the Supreme Court held that the Omaha reservation was not disestablished despite a 100-year history of treating the lands as belonging to Nebraska and residents of the area being largely noncitizens.46

CREEK RESERVATION HANGS IN THE BALANCE OF THE SUPREME COURT, LITERALLY

In order for the 10th Circuit’s decision that the Creek Reservation was not disestablished to stand, four of the Supreme Court justices must vote in its favor (as Justice Gorsuch, who participated in adjudication of the 10th Circuit appeal while presiding there, recused himself from the Supreme Court’s proceedings). While it is always difficult to predict the vote of any particular justice, some observations are worth noting based upon the dialogue of the court during oral arguments.

Justices Kagan and Sotomayer seemed most interested in analyzing the case from the traditional disestablishment test standpoint, with Justice Kagan hammering home the point that the well-established test is congressional intent. Although Justice Thomas did not ask questions, he wrote the opinion in Nebraska v. Parker and is a textualist who usually adheres closely to the text of a statute. Justice Breyer began his questions by asking about the existence of statutory language disestablishing the Creek Reservation and noted that reservations exist with limited tribal jurisdiction, although he went on to ask questions about the practical effects of a finding that the Creek Reservation continues to exist and the extent of the Creek Nation’s authority.

Justice Roberts and Justice Alito asked questions about the possible consequences of a finding that the Creek Reservation continues to exist, as well as the level of the Creek Nation’s authority retained over it. Justice Kavanaugh suggested examining the historical context, rather than specific statutory language alone, and referenced the importance of stability. The one question Justice Ginsburg asked suggested she may be concerned about taxation implications if the Creek Reservation is found to continue to exist.

After oral arguments, the Supreme Court directed the parties, the solicitor general and the Creek Nation to file supplemental briefs. Based on its questions, it appeared the court was looking for a way to find that Oklahoma has criminal jurisdiction over the land without finding the Creek Reservation was disestablished. The court directed the briefs to address whether any statute grants Oklahoma jurisdiction over the prosecution of crimes committed by Indians within the Creek Reservation, regardless of whether the reservation status remains, and whether there are circumstances under which land qualifies as a reservation but does not meet the statutory Indian country definition.

After much anticipation, on June 27, 2019, the Supreme Court issued a statement that it would not decide the case during its current term but would place the case on the calendar for re-argument in the upcoming term. This unusual move only adds to the question of what the Supreme Court will do: follow well-settled law or cave to arguments that the sky would fall if tribes were found to have jurisdiction over their own land.47

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

William R. Norman Jr. is a partner with the law firm Hobbs, Straus, Dean & Walker LLP. For the past 25 years, his practice has been focused on promoting and defending tribal rights for Indian tribes/Alaskan Natives and tribal organizations. Prior to joining the law firm, he served as a clerk for the United States Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit.

1. Negonsott v. Samuels, 507 U.S. 99, 102 (1993).

2. 18 U.S.C. §1153(a).

3. 18 U.S.C. §1151.

4. See Seymour v. Superintendent of Wash. State Penitentiary, 368 U.S. 351, 359 (1962); United States v. Celestine, 215 U.S. 278, 290-91 (1909); United States v. Thomas, 151 U.S. 577, 586 (1894).

5. Okla. Tax Comm’n v. Sac & Fox Nation, 508 U.S. 114, 123 (1993) (“Congress has defined Indian country broadly to include formal and informal reservations, dependent Indian communities, and Indian allotments, whether restricted or held in trust by the United States.”).

6. Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553, 556 (1903).

7. Solem v. Bartlett, 465 U.S. 463, 468-72 (1984) (noting its decision relied on factors discussed in previous cases examining whether reservation disestablishment had occurred). These factors have since been affirmed and applied by the Supreme Court. See, e.g., South Dakota v. Yankton Sioux Tribe, 522 U.S. 329 (1998); Hagen v. Utah, 510 U.S. 399 (1994).

8. See, e.g., South Dakota v. Yankton Sioux Tribe, 522 U.S. 329, 343 (1998) (citing United States v. Dion, 476 U.S. 734, 738 (1986)).

9. Mattz v. Arnett, 412 U.S. 481, 497 (1973).

10. Solem v. Bartlett, 465 U.S. 463, 470-72 (1984). See also Nebraska v. Parker, 136 S. Ct. 1072, 1079-80 (2016).

11. Nebraska v. Parker, 136 S. Ct. 1072 (2016).

12. In its removal and subsequent dealings, it was loosely lumped into a group of tribes referred to as “the Five Civilized Tribes,” also relocated from the southeastern United States and also placed on reserved lands held in “fee” by the tribes.

13. 31 Stat. 861 (1901).

14. 34 Stat. 137 (1906).

15. 34 Stat. 267 (1906).

16. Ironically, Congress has effectively rejected Oklahoma’s assumption by equating the so-called “former reservations” in Oklahoma to existing reservations elsewhere. See, e.g., 25 U.S.C. §2719(a)(2)(A) (treating “former reservations” in Oklahoma same as reservations existing when Indian Gaming Regulatory Act was enacted); 25 U.S.C. §2020(d)(1) (“Tribes that receive grants under this section shall use the funds made available through the grants ... to facilitate tribal control in all matters relating to the education of Indian children on reservations (and on former Indian reservations in Oklahoma)[.]”).

17. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 903-04 (10th Cir. 2017).

18. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 937-38 (10th Cir. 2017) (citing Nebraska v. Parker, 136 S. Ct. 1072, 1080 (2016)) (emphasis in original). The 10th Circuit expressly did not decide whether the land qualified as allotment land. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 908 n.8 (10th Cir. 2017).

19. 138 S. Ct. 2026 (2018).

20. Brief for Petitioner at 23, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. July 23, 2018).

21. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 4-7, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. July 30, 2018).

22. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 5-7, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. July 30, 2018).

23. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 18, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. July 30, 2018).

24. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 5, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. July 30, 2018).

25. Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 28-33, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. July 30, 2018).

26. Brief for Respondent at 1, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Sept. 19, 2018); Brief for Amicus Curiae Muscokee (Creek) Nation in Support of Respondent at 15-19, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Sept. 26, 2018).

27. Transcript of Oral Argument at 32-34, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018).

28. Transcript of Oral Argument at 36-40, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018).

29. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 934-51 (10th Cir. 2017) (discussing eight statutes identified by Oklahoma and determining that “[n]ot only do the State’s statutes lack any language showing disestablishment, they show Congress’s continued recognition of the Reservation’s boundaries”).

30. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 951 (10th Cir. 2017).

31. Indian Country, U.S.A., Inc. v. Okla. ex rel. Okla. Tax Comm’n, 829 F.2d 967, 975 n.3, 980 n.5 (10th Cir. 1987), cert. denied, 487 U.S. 1218 (1988).

32. Transcript of Oral Argument at 45-50, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018). Arguably, the United States, while possessing authority to remove federal recognition, cannot dissolve a tribe’s government.

33. Brief for Respondent at 20, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Sept. 19, 2018); Brief for Amicus Curiae Muscokee (Creek) Nation in Support of Respondent at 15, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Sept. 26, 2018); see also Mattz v. Arnett, 412 U.S. 481, 497 (1973).

34. Transcript of Oral Argument at 66, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018).

35. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 964-65 (10th Cir. 2017).

36. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 947 (10th Cir. 2017) (“In the Oklahoma Enabling Act, the final statute the State relies on, Congress did not dissolve the Creek government, but it granted permission to the inhabitants of both the Territory of Oklahoma and the Indian Territory to adopt a constitution and seek admittance into the Union as the State of Oklahoma.”).

37. 34 Stat. 267 (1906).

38. Okla. Const. art. I, §3 (“Unappropriated public lands - Indian lands - Jurisdiction of United States. The people inhabiting the State do agree and declare that they forever disclaim all right and title in or to any unappropriated public lands lying within the boundaries thereof, and to all lands lying within said limits owned or held by any Indian, tribe, or nation; and that until the title to any such public land shall have been extinguished by the United States, the same shall be and remain subject to the jurisdiction, disposal, and control of the United States.”).

39. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 953-54 (10th Cir. 2017).

40. Transcript of Oral Argument at 42-44, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018).

41. Transcript of Oral Argument at 41-42, 68-75, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018).

42. They cited City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y., 544 U.S. 197 (2005).

43. Transcript of Oral Argument at 47-49, 62-63, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Nov. 27, 2018).

44. See Brief for Amicus Curiae Muscokee (Creek) Nation in Support of Respondent at 26-31, Carpenter v. Murphy, No. 17-1107 (U.S. Sept. 26, 2018).

45. Murphy v. Royal, 875 F.3d 896, 964 (10th Cir. 2017).

46. Nebraska v. Parker, 136 S. Ct. 1072, 1078 (2016).

47. Unfortunately, the space limitations herein preclude a more exacting examination of a number of legal issues related to the subject matter, including, but not limited to the following: the extent of limitations placed on tribes’ exercise of jurisdiction even over their reservation land; the history of how and why Oklahoma tribes have suffered under the faulty assumption that their reservations were disestablished; ways tribes in Oklahoma do have jurisdiction over some of their land, including trust land and allotments; how the decision in this case affects other tribes in Oklahoma, recent Supreme Court cases in addition to Nebraska v. Parker upholding reservation boundaries or other treaty rights; and the ways in which tribes in Oklahoma have exercised their governmental authority and benefited Oklahoma more generally.