Oklahoma Bar Journal

The Right to Trial by Jury for Termination of Parental Rights

By Evan Humphreys

Who would you want to decide if you could ever see your children again? Or whether you could ever see your parents again? Would you want a group of six strangers to choose? What about a judge who may have already decided once before to keep your children or parents away from you?

There are no simple answers to these grim questions. But parents and children must frequently answer questions like these in juvenile deprived proceedings. When a court places custody of a minor with the state, a time may come when the government (or child) wishes to permanently sever the parent-child relationship. In the parlance of juvenile deprived law, this permanent severance is known as “termination.”

This article will explore the foundations of – and limitations on – the right to trial by jury on the issue of termination. With this information, practitioners can better assist their clients in answering these difficult questions on an informed basis.

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATION

The Seventh Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in common law actions if the amount in dispute is more than $20. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has not yet held that this amendment applies to the states.[1] As such, there is currently no precedential authority establishing a right to trial by jury in any kind of civil case in state court under the U.S. Constitution.

Despite the lack of federal authority, the right to a jury trial does exist under Oklahoma law. Article II, Section 19 of the Oklahoma Constitution says, “The right of trial by jury shall be and remain inviolate.” But this right is not as boundless as it appears. It is limited to actions where the right to a jury trial was guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution or the common law at the time of its adoption. But this limitation itself has an important caveat. The guarantee of a right to trial by jury is so limited “except as modified by the Constitution itself.”[2]

This exception is key to understanding the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s ultimate application of Article II, Section 19 to termination proceedings. The court first wrestled with this application some 50-odd years ago.[3] The parent in that case argued that they were entitled to a jury trial on the issue of termination because parental rights are fundamental. They also cited the Oklahoma Constitution and the statute in effect at the time. The court rejected each argument and held that the parent was not entitled to have a jury determine whether their rights to their children should be permanently ended.

A decade later, the court revisited this issue in A.E. v. State.[4] In this case, the court’s analysis was informed by the fundamental nature of parental rights and a categorical rejection of the idea that parental conduct has any bearing on a pure question of law. With these principles in mind, the court zeroed in on the “except as modified by the Constitution itself” language it had previously avoided.

The court found this language to be critical because of a 1969 amendment to Article II, Section 19, which specifically provided for the right to trial by jury in “juvenile proceedings.” The court held that this evidenced the intent of the framers of the amendment to grant a right to a jury in termination trials. As such, the court explicitly overruled its prior cases and concluded by stating, “Parental rights are too precious to be terminated without the full panoply of protections afforded by the Oklahoma Constitution.”

It is worth noting that the people of Oklahoma amended Article II, Section 19 again in 1990. This latest amendment removed the specific reference to “juvenile proceedings” and other types of cases that were enumerated in this section at the time A.E. was decided. However, the state Supreme Court has already held that the 1990 amendment does not change its holding in A.E.[5] While the court did not explain its reasoning, its decision is sound based on the wording of the state question that created this amendment.

The state question framed Article II, Section 19 as providing for six-person juries “only in some civil trials.” It went on to say that the measure would change the constitution to provide for 12-person juries in felonies and civil cases involving $10,000 or more, but a six-person jury would be required in “other trials.” The state question placed no limitation on these “other trials.” Indeed, it states that litigants may agree to a lesser number of jurors “in any case.”[6] As such, it is reasonable to conclude that the framers of the 1990 amendment intended to expand the right to trial by jury rather than reduce it.

Finally, while the language of Article II, Section 19 is expansive, case law has only ever applied it to parents. It has never explicitly been held to guarantee a child’s right to trial by jury. Nevertheless, children are full parties to deprived proceedings.[7] Children also enjoy constitutional rights.[8] As such, there should be no doubt that children have the same constitutional right to trial by jury that is guaranteed to their parents. Most importantly, children can assert this right independent of their parents’ decisions.

STATUTORY FOUNDATION

The Oklahoma Constitution is not the only guarantee of this right. Article 1 of Title 10A: The Children and Juvenile Code (the children’s code or the code) gives a parent, a child or the state the right to demand a jury trial. However, by statute, that demand is strictly limited to the issue of termination of parental rights.

The code says the issue of adjudication – essentially, whether the juvenile deprived case should continue at all – must be tried to the bench.[9] Even if the state files for immediate termination of parental rights, the code requires the bench to determine whether the children should be adjudicated as deprived while the jury only decides the issue of termination.[10] No published case from the Oklahoma Supreme Court addresses the application of Article II, Section 19 to these statutes. One published case from the Court of Civil Appeals held that there was no right to a jury trial at a “dispositional hearing” – an informal proceeding where the rules of evidence do not apply – but did not engage in a robust constitutional analysis as to why.[11]

If nothing else, the statutory right to trial by jury remains as to the issue of termination. Once the demand for a jury trial has been made, it must be granted unless waived. This language indicates that a party who initially demands such a trial may later waive a jury, and the court is not bound by the prior demand. Absent a waiver, the trial court must then issue a scheduling order within 30 days, and the trial must begin within six months of the filing of that scheduling order. The court may go beyond this six-month period if it issues written findings of fact that there are exceptional circumstances to do so or if all the parties agree.[12] Starting Nov. 1, 2025, bench trials must begin within 90 days of the scheduling order’s filing, although that time may be extended in the same manner as jury trials.[13]

But can the district court still hold a jury trial if all the parties agree to waive their right to one? There are no published cases answering this question. However, the language of the statute seems to indicate that the answer is yes. The relevant language states that a jury trial must be granted unless waived, “or the court on its own motion may call a jury to try any termination of parental rights case.” The quoted language is an independent clause that does not need to rely on any preceding part of the sentence to stand as a complete thought. It is also joined by the conjunction “or,” indicating a choice among options. Finally, the quoted language says the court can bring in a jury to try “any” termination case, which would presumably include one in which all other parties have waived a jury. As such, there are reasons to believe the court can force a jury trial even if none of the parties desire one.

LIMITATIONS ON THE RIGHT TO JURY TRIAL

While A.E. v. State affirmed the constitutional right to trial by jury in Oklahoma, the court noted that this right may be given up “by voluntary consent or waiver.”[14] Exactly what qualifies as “voluntary consent or waiver” is an ongoing issue in the appellate courts.

Inaction often qualifies. For example, in Matter of E.J.T., the Oklahoma Supreme Court explored whether the mother’s failure to act waived her right to a jury trial.[15] After the state moved to terminate her rights, a court minute was filed claiming the mother waived trial by jury and requested a bench trial. The mother was served with a copy of this minute but never asserted that its contents were incorrect. When a bench trial was later held, the mother never objected to proceeding this way or otherwise demanded a trial by jury until she raised the error on appeal. By failing to demand a jury at the trial level in any way, the court held that the mother waived her right to the same.

Nevertheless, the right to a jury trial can be lost even when it has been demanded. Currently, the Oklahoma children’s code empowers trial courts to deem a party’s right to a jury trial waived if they fail to appear “for such trial.”[16]

Previously, as decided by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in Matter of H.M.W., failing to appear “for such trial” only waived the right to be present and required a trial by jury in absentia.[17] However, the Oklahoma Legislature subsequently amended that part of the children’s code and removed the language that created this result. As such, jury trials in absentia in termination cases are no longer permitted under that particular statute.[18]

While Matter of H.M.W. is no longer good law on this issue, another section of the children’s code still states that a parent’s failure to appear in person, “or to instruct his or her attorney to proceed in absentia at the trial,” is equivalent to consenting to the termination.[19] The Supreme Court did not address this language allowing a person “to instruct their attorney to proceed in absentia” when it overruled Matter of H.M.W. It remains to be seen how the courts will interpret the ability to demand a jury trial in absentia in light of this statute.

In analyzing the revised statute, the Oklahoma Supreme Court held that it was constitutional for the Legislature to create a process where a party’s failure to appear for a jury trial may be considered a waiver of their right to that form of trial. Still, the court required that a party receive some form of notice that their failure to appear “for such trial” could result in the loss of that right.[20] While the court did not delineate what that notice must look like, the children’s code requires petitions and motions for termination of parental rights to be served in essentially the same manner as initial pleadings in other civil cases.[21]

But failing to appear for just any hearing does not result in the loss of the right to a jury trial. The phrase “for such trial” has been examined by one division of the Court of Civil Appeals in a published opinion. In Matter of J.B., the mother demanded a jury trial on the state’s motion to terminate her parental rights.[22] A jury trial was set but then continued multiple times. The mother failed to appear at a subsequent hearing, which was not for the purpose of holding a jury trial. Nevertheless, the trial court took the mother’s failure to appear as her consent to the termination of her rights. Division IV found that her absence from a nonjury trial setting did not waive her right to trial by jury. Under this rationale, a party should only lose this right if they fail to appear for their scheduled jury trial. Skipping any other setting in front of the court does not create a consent termination.

CONSIDERATIONS IN DEMANDING OR WAIVING A JURY TRIAL

There is no concrete set of factors that must be considered when advising a client on whether they should proceed with a bench or jury trial on the issue of termination. Nevertheless, there are some common considerations an attorney should discuss when the client is making this difficult decision.

The first consideration is the judge. Usually, the judge sitting as the trier of fact in a termination bench trial is the same judge who has presided over the case since the beginning. Therefore, the attorney and the client should have a sense of the judge’s perception of the case. If it seems like the judge may be open to the client’s position, then proceeding to a bench trial can be a viable option. But if there is some reason to believe that the judge has a less favorable view of the client’s desired outcome, then a jury trial may be the better alternative.

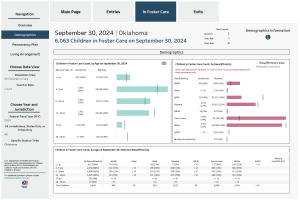

Demographics of children in foster care, as of September 2024. Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. View at http://bit.ly/47amlT4.

The second consideration is the potential jury pool itself. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the majority of Oklahoma children in foster care in September 2023 were nonwhite.[23] However, across the country, “people of color are significantly underrepresented in the jury pools from which jurors are selected.”[24] Financial barriers to jury duty may also mean that your pool of jurors may not have experienced the same hardships a client in a termination case may have faced.[25]

All of this is to say that the jury in a termination trial may not truly be the client’s peers. The client will have to consider the potential jury pool and whether they prefer to have their case judged by this likely group of individuals or the court.

Finally, it must be noted that parents and children may have options other than proceeding to trial. If reunification is not possible or not what the client wants, Title 30 guardianships, permanent guardianships and adoptions with visitation may be more palatable resolutions.

Of course, the decision ultimately belongs to the client. Even if the local practice is to waive jury trial in every case, practitioners must advise their clients of their constitutional and statutory right to a jury trial as well as the ways in which that right can be lost. It will always be a difficult choice, but with good advice and information, at least it can be an informed choice.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Evan Humphreys is the managing attorney of appellate practice for the Oklahoma Office of Family Representation, which contracts with private attorneys to provide high-quality legal representation to parents and children in juvenile deprived cases at trial and on appeal.

ENDNOTES

[1] Minneapolis & St. L.R. Co. v. Bombolis, 241 U.S. 211, 217 (1916).

[2] Keeter v. State ex rel. Saye, 1921 OK 197, ¶5, 198 P. 866.

[3] J.V. v. State Dep't of Insts., Social & Rehab. Servs., 1977 OK 224, 572 P.2d 1283.

[4] A.E. v. State, 1987 OK 76, 743 P.2d 1041.

[5] Gray v. Upp, 1997 OK 98, ¶2, 943 P.2d 592.

[6] State Question No. 623, available at http://bit.ly/46Fy8tF (last accessed July 22, 2025).

[7] 10A O.S. §1-4-306(A)(2)(c).

[8] Planned Parenthood of Cent. Mo. v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52, 74 (1976).

[9] 10A O.S. §1-4-601(D)(3).

[10] 10A O.S. §1-4-502(A).

[11] Matter of K.S., 1990 OK CIV APP 106, ¶8, 807 P.2d 292.

[12] 10A O.S. §1-4-502(B).

[13] Children, 2025 Okla. Sess. Law Serv. Ch. 375 (H.B. 1965).

[14] A.E., at ¶22.

[15] Matter of E.J.T., 2024 OK 14, 544 P.3d 950.

[16] 10A O.S. §1-4-502(B).

[17] Matter of H.M.W., 2013 OK 44, ¶7, 304 P.3d 738.

[18] Matter of F.B., 2025 OK 25, P.3d.

[19] 10A O.S. §1-4-905(A)(5).

[20] F.B., at ¶19.

[21] 10A O.S. §1-4-905(A).

[22] Matter of J.B., 2024 OK CIV APP 22, 558 P.3d 39.

[23] See The Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Dashboard 2025, Admin. for Children & Families, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Servs., available at http://bit.ly/47amlT4 (last accessed Oct. 14, 2025).

[24] “Race and the Jury,” Equal Justice Initiative website, http://bit.ly/4gWWCC6 (last accessed Sept. 25, 2025).

[25] Jule Pattison-Gordon, “How Courts Are Trying To Make Jury Duty More Appealing,” Governing website, March 25, 2025, http://bit.ly/4mYeSfU.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 96 No. 9 (November 2025)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.