Oklahoma Bar Journal

The Rediscovery of Indian Country in Eastern Oklahoma

By Conor P. Cleary

The federal building in Muskogee housed the U.S. district court offices, the post office and the headquarters of the Five Civilized Tribes. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

The existence of “Indian country” – generally defined as all land within Indian reservations, dependent Indian communities and Indian allotments[1] – has legal significance because it is “the benchmark for approaching the allocation of federal, tribal and state authority with respect to Indians and Indian lands.”[2] Generally, the federal and tribal governments have primary authority over Indians within Indian country, while state jurisdiction is more limited.[3] Outside of Indian country, on the other hand, states generally have jurisdiction over Indians and non-Indians alike.[4]

One might reasonably assume that the state of Oklahoma, home to 39 different Indian tribes, would have significant amounts of Indian country within its borders, particularly in the eastern part of the state, which, immediately prior to statehood, was the Indian Territory. Yet, as recently as 1979, the Oklahoma attorney general categorically concluded that “in Eastern Oklahoma, there is no ‘Indian Country’ as that term is used in federal law.”[5] Indeed, the conventional wisdom of the federal and state courts, many historians and academics and Oklahoma’s political leaders was that there was little to no Indian country left in eastern Oklahoma and, in any event, the state had obtained primary jurisdiction over it, including the exclusive authority to prosecute crimes committed there. In reaching this conclusion, many court decisions misapprehended fundamental principles of federal Indian law, instead “substituting stories for statutes” by employing assimilationist suppositions about the “civilized” nature of tribes in eastern Oklahoma and distinguishing them from “Reservation Indians.”[6]

Of course, after McGirt v. Oklahoma, where the Supreme Court ruled that the Muscogee Reservation was never disestablished by Congress, we know this conclusion is erroneous.[7] But while McGirt is the most recent and significant pronouncement on the existence of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma, it is the culmination of several earlier decisions by federal and Oklahoma state courts, issued only in the 1980s and 1990s, that began to “rediscover” categories of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma and repudiate the reasoning of earlier decisions.

This article summarizes the historical circumstances that led courts to draw a distinction between the western and eastern halves of the state, generally recognizing the existence of Indian country in the former while categorically denying its existence in the latter. It begins with a summary of tribal land tenure before Oklahoma's statehood, the subsequent allotment of tribal lands and the admission of Oklahoma to the Union. It then surveys the court decisions from the first half of the 20th century that denied the continuing existence of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma.

The article then explains changes in federal Indian policy during the New Deal era of the 1930s and 1940s, Oklahoma’s decision in the 1950s not to assume jurisdiction over Indian country within the state pursuant to Public Law 280 and the reinvigoration of tribes in Oklahoma during the self-determination era in the 1960s and 1970s. It demonstrates how these changes in federal policy prompted federal and Oklahoma state courts in the 1980s and 1990s to repudiate the earlier decisions denying the existence of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma.

THE INDIAN TERRITORY AND THE ROAD TO OKLAHOMA STATEHOOD

Before statehood, Oklahoma was part of the Indian Territory. In the 1830s, the Five Tribes of Oklahoma – the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole nations – were forcibly relocated to Indian Territory from the southeastern United States.[8] Treaties executed between the federal government and the tribes promised them lands in the Indian Territory for use as a permanent homeland.[9] After the Civil War, each of the Five Tribes executed a treaty with the United States that reduced their territories but preserved reservations for them.[10] The federal government used the western part of Indian Territory ceded by the Five Tribes for the relocation of other Indian tribes, primarily those indigenous to parts of the western United States. In 1890, these lands were organized as the Oklahoma Territory.[11]

Members of the Dawes Commission in 1902. The commission was charged with dividing tribal land into plots that were then divided among tribal members. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

There was an important difference in the land tenure of the reservations of the Five Tribes in the Indian Territory and those in the Oklahoma Territory. Pursuant to their treaties, the Five Tribes received a fee patent to their lands.[12] This meant the tribes themselves were the legal title owners of their reservation lands subject only to a restriction on alienation by the federal government. These lands are sometimes referred to as “restricted fee” lands. In Oklahoma Territory, however, reservation lands were held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of the tribes. These lands are commonly known as “trust lands” and are representative of most Indian country in the United States. Although today there is no material difference between restricted and trust lands for most purposes,[13] at one time, both federal and state courts relied on this difference in the land tenure of reservations in the Indian and Oklahoma territories to conclude that the lands of the Five Tribes and their members were no longer Indian country.

In the 1880s, the federal government began a policy of breaking up tribal reservations by allotting parcels of land to individual tribal members.[14] The General Allotment Act (also known as the Dawes Act), the first comprehensive allotment legislation, gave tribal members allotments of either 80 or 160 acres.[15] The law authorized the United States to dispose of any unallotted or “surplus” lands to non-Indian settlers, paving the way for non-Indian ownership of reservation lands. The allotments were held in trust by the federal government for the allottee and their heirs for a period of time (originally 25 years), during which the allottee could not alienate or encumber the land without federal approval.[16] These allotments are commonly referred to as “trust allotments.” Upon expiration of the trust period, federal supervision ceased, and the Indian owners became subject to the civil and criminal laws of the state.[17]

The General Allotment Act expressly did not apply to the Five Tribes.[18] However, Congress later applied the allotment policy to their lands.[19] Each tribe negotiated an allotment agreement with the Dawes Commission, which created rolls of tribal citizens[20] and gave each citizen an allotment of tribal lands pursuant to the terms of each tribe’s allotment agreement.[21] Since the tribes possessed a fee patent to the underlying reservations, the allotments to tribal members were also in fee, subject to a restriction on alienation for a period of years.[22] These are known as “restricted allotments.”[23]

In 1906, Congress enacted the Five Tribes Act “[t]o provide for the final disposition of the affairs of the Five Civilized Tribes in the Indian Territory.”[24] Although the act contemplated the “dissolution of the tribal governments” upon the completion of the allotment process,[25] it nevertheless provided that “the tribal existence and present tribal governments of [the Five Tribes] are hereby continued in full force and effect for all purposes authorized by law[.]”[26] That same year, Congress also passed the Oklahoma Enabling Act providing for the admission of the state of Oklahoma.[27] “In passing the enabling act for the admission of the state of Oklahoma ... Congress was careful to preserve the authority of the government of the United States over the Indians, their lands and property, which it had prior to the passage of the act.”[28] Specifically, the Enabling Act required the state to disclaim “all right and title” to Indians and their lands[29] and provided that nothing in Oklahoma’s Constitution would be construed to “limit or impair the rights of person or property pertaining to the Indians ... or to limit or affect the authority of the Government of the United States to make any law or regulation respecting such Indians, their lands, property, or other rights by treaties, agreement, law or otherwise, which it would have been competent to make if this Act had never been passed.”[30]

EARLY DECISIONS DENYING THE EXISTENCE OF INDIAN COUNTRY IN EASTERN OKLAHOMA

Despite these provisions of the Enabling Act acknowledging the continuing existence of Indian lands in the state and preserving federal authority over the same, early federal and Oklahoma case law routinely concluded that there was little to no Indian country left in Oklahoma.

Reservations

Beginning with the broadest category of Indian country, Indian reservations, the early conclusion was that there were few, if any, reservations remaining in Oklahoma.[31] For reservations in western Oklahoma, courts started from the premise that the tribes initially possessed reservations but concluded that the reservations had been disestablished by allotment.[32] In eastern Oklahoma, however, particularly with respect to the Five Tribes, courts reasoned that Oklahoma tribes never had reservations to begin with due to the unique history of the Indian Territory. For example, in one case, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals concluded that Congress had “take[n] the Indians in the Indian Territory out of the category of Reservation Indians.”[33] The state of Oklahoma continued to make this argument as recently as McGirt.[34]

Allotments

Since the assumption was that there were no longer Indian reservations in Oklahoma, most cases in the first half of the 20th century considered whether Indian allotments carved out of the prior reservations remained Indian country and free from state jurisdiction. While courts generally concluded that allotments located in the former Oklahoma Territory were Indian country,[35] they reached the opposite conclusion for allotments in the former Indian Territory.

In Ex Parte Nowabbi, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals held that the state had jurisdiction to prosecute a murder committed by one Choctaw Indian against another on a restricted Choctaw allotment.[36] The court based its conclusion on a dubious interpretation of an amendment to the General Allotment Act. The amendment, which extended the trust restrictions on most allotments and delayed subjecting allottees to state jurisdiction, contained a proviso that it did not apply to “any Indians in the former Indian Territory.”[37] The court concluded that the implication of excepting the Indians in the Indian Territory was that Congress had intended to subject them to state jurisdiction.[38] The problem with this reasoning was that Congress had exempted most of the tribes in the Indian Territory from the General Allotment Act to begin with, so their exception from an amendment to the General Allotment Act was unsurprising.

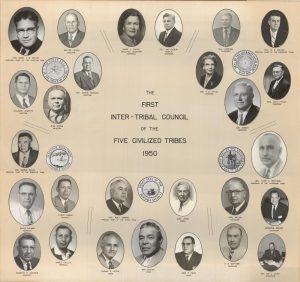

Photographs of the members of the First Inter-Tribal Council of the Five Civilized Tribes in 1950. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

Similarly, others argued that statutory enactments paving the way for Oklahoma statehood had terminated the existence of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma. For example, in the 1950s, the governor of Oklahoma declined to affirmatively assume jurisdiction over Indian country in Oklahoma based on the assumption that there was no longer any Indian country over which to assume jurisdiction.[39] Likewise, the Oklahoma attorney general reasoned in a 1979 opinion that as a result of statutes like the Curtis Act of 1898 and the Five Tribes Act of 1906, which abolished the tribal courts and contemplated the “dissolution of the tribal governments,” respectively, “[a]ll tribal government in the former Indian Territory merged with and became a part of the state government of the State of Oklahoma.” This gave the state exclusive jurisdiction in eastern Oklahoma, including the authority to prosecute crimes committed by or against Indians.[40]

CHANGES IN FEDERAL INDIAN POLICY: 1934-1976

While courts in Oklahoma remained resistant to the existence of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma well into the second half of the 20th century, changes in federal Indian policy during the 1930s to 1960s foreshadowed reexamination of these rulings in later years.

First, during the New Deal Era, Congress enacted the Indian Reorganization Act, ending the allotment policy and allowing tribes to reorganize and reestablish their governments.[41] Congress also established a process whereby the tribes could reestablish and expand their land base by acquiring land and having the federal government hold it in trust for their benefit. This created large amounts of tribal trust land within Oklahoma, notwithstanding the belief there were no longer formal reservations.

Second, Congress codified a definition of Indian country in the U.S. Code. This definition overrode common law conceptions of Indian country and firmly established reservations, dependent Indian communities and allotments as discrete forms of Indian country.[42] The statute made no exception for tribes in Oklahoma.

Third was the passage of Public Law 280, a statute allowing states to obtain jurisdiction over Indian country within their territories. During the late 1940s and 1950s, Congress pursued a policy of termination that would end federal supervision over Indians and tribes and subject them to state law.[43] Public Law 280 transferred criminal jurisdiction over Indian lands in five “mandatory states” with an option for all other states to assume jurisdiction by affirmative legislation. Oklahoma, however, never acted to assume jurisdiction over Indian country pursuant to Public Law 280 because of the conventional wisdom of elected leaders that Oklahoma already had jurisdiction over all Indian country in the state.[44] Oklahoma’s overconfidence turned out to be a tactical error as courts later construed its failure to affirmatively assume jurisdiction as an admission that it did not have jurisdiction over Indian country within the state.

Finally, in the late 1960s and 1970s, federal Indian policy shifted decisively away from the termination of tribes to an era of tribal self-determination.[45] This era saw a reinvigoration of tribes in Oklahoma, particularly the Five Tribes, which began to strengthen their tribal institutions, including their tribal councils and courts.[46] This rebirth of tribal sovereignty undermined the argument that the tribes of Oklahoma had merged into the state government. Further, in the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968, Congress amended Public Law 280 to require tribal consent before a state could act to assume jurisdiction over Indian country. No Oklahoma tribes consented to state jurisdiction. This reinforced the conclusion that Oklahoma’s failure to assume jurisdiction pursuant to Public Law 280 meant it did not have jurisdiction within Indian country in the state.

THE REDISCOVERY OF INDIAN COUNTRY IN EASTERN OKLAHOMA

These changes in federal Indian policy began to be reflected in Oklahoma court decisions in the late 1970s and 1980s. In State v. Littlechief, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, adopting a decision by the United States District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, reaffirmed that an original Kiowa allotment in western Oklahoma was Indian country under 18 U.S.C. §1151(c).[47] Although the state of Oklahoma continued to argue for a different treatment in eastern Oklahoma, the Oklahoma Supreme Court blunted the reach of this position when it extended the Littlechief holding to Quapaw and Seneca-Cayuga trust allotments in May v. Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma.[48] Reasoning that the allotment of both tribes’ lands had been done pursuant to the provisions of the General Allotment Act, the same legislation authorizing allotments to the western Oklahoma tribes, the Oklahoma Supreme Court found that the location of these tribes within the former Indian Territory in eastern Oklahoma did not remove the allotments from Indian country.[49]

Once the Oklahoma Supreme Court recognized that certain allotments in eastern Oklahoma could qualify as Indian country, courts soon held that the restricted allotments of the Five Tribes’ lands were also Indian country under 18 U.S.C. §1151(c). In 1989, in State v. Klindt, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, following Seneca-Cayuga, overruled Nowabbi in holding that an original Cherokee allotment was Indian country.[50] Three years later, in Cravatt v. State, the court was even more explicit, firmly rejecting a “different judicial treatment for incidents involving members of the Five Civilized Tribes,” noting there was “no foundation for this position.”[51] That same year, the 10th Circuit reached a similar result in United States v. Sands, where it held that a restricted Muscogee (Creek) allotment qualified as Indian country.[52] In these cases, the courts cited both the express inclusion of allotments in the statutory definition of Indian country as well as Oklahoma’s failure to assume criminal jurisdiction under Public Law 280 in support of its conclusion.

Finally, the courts began to undo their complete rejection of the existence of reservations in Oklahoma by finding that lands taken into trust for tribes pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act and Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act qualified as Indian country under 18 U.S.C. §1151(a). Although tribal trust lands are not expressly mentioned in the statutory definition of Indian country, a pair of federal court opinions emphasized the purpose for which the lands were acquired rather than any formal label. Since trust lands were acquired for use by Indians and were under federal supervision, that was sufficient to qualify them as Indian country.[53] These rulings were later affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1990s.[54]

CONCLUSION

For most of Oklahoma’s first century, state and federal courts denied the existence of Indian country in eastern Oklahoma based on a false dichotomy between the former Oklahoma and Indian territories, grounded more in legend than in law, that perversely punished the Five Tribes for their perceived assimilation. Only in the past generation have courts in Oklahoma, prompted by changes in federal Indian policy by Congress, rediscovered the existence of Indian country in the eastern half of the state, beginning with the recognition of Indian allotments, then tribal trust lands and finally the reaffirmation of reservations in McGirt.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Conor P. Cleary is the Tulsa field solicitor for the U.S. Department of the Interior. The views expressed are those of Mr. Cleary and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of the Interior or the United States government.

ENDNOTES

[1] See 18 U.S.C. §1151(a)-(c). The definition provides in full:

Except as otherwise provided in sections 1154 and 1156 of this title, the term “Indian country”, as used in this chapter, means (a) all land within the limits of any Indian reservation under the jurisdiction of the United States Government, notwithstanding the issuance of any patent, and, including rights-of-way running through the reservation, (b) all dependent Indian communities within the borders of the United States whether within the original or subsequently acquired territory thereof, and whether within or without the limits of a state, and (c) all Indian allotments, the Indian titles to which have not been extinguished, including rights-of-way running through the same.

[2] Indian Country, U.S.A., Inc. v. Okla. Tax Comm’n, 829 F.2d 967, 973 (10th Cir. 1987).

[3] But see Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 142 S. Ct. 2486 (2022). More specifically, states generally lack jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed by Indians within Indian country. McGirt v. Oklahoma, 140 S.Ct. 2452, 2459 (2020) (citing Negonsott v. Samuels, 507 U.S. 99, 102-03 (1993)). Either the federal or tribal government has jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed by Indians in Indian country depending on the nature of the offense. The federal government prosecutes certain “major” crimes while the tribe prosecutes other offenses. See Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676, 680 n.1 (1990), superseded by statute as held in U.S. v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004). In the civil context, states generally lack authority over Indians in Indian country, see McClanahan v. Arizona Tax Comm’n, 411 U.S. 164 (1973), while they retain greater authority over non-Indians unless such jurisdiction would infringe tribal self-government or is preempted by federal law. See Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217 (1959); White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker, 448 U.S. 136 (1980). Tribes have civil jurisdiction over non-Indians in Indian country. However, if the non-Indian conduct at issue takes place on land within a reservation but held in fee by non-Indians, then tribal jurisdiction is generally only allowed where there is a consensual relationship between the non-Indian and the tribe or where the non-Indian conduct threatens or has a direct effect on the political integrity, economic security or health or welfare of the tribe. See Montana v. U.S., 450 U.S. 544 (1981).

[4] Mescalero Apache Tribe v. Jones, 411 U.S. 145 (1973).

[5] 11 Okla. Op. Att’y. Gen. 345 (1979), available at 1979 WL 37653, at *8.

[6] See, e.g., Ex Parte Nowabbi, 61 P.2d 1139, 1154 (Okla. Crim. App. 1936); see also Okla. Tax Comm’n v. U.S., 319 U.S. 598, 603 (1943) (suggesting that the “underlying principles” of federal Indian law “do not fit the situation of the Oklahoma Indians”).

[7] The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals subsequently extended McGirt’s holding to the reservations of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and Quapaw nations. See Hogner v. State, 500 P.3d 629 (Okla. Crim. App. 2021) (Cherokee Reservation); Bosse v. State, 499 P.3d 771 (Okla. Crim. App. 2021) (Chickasaw Reservation); Sizemore v. State, 485 P.3d 867 (Okla. Crim. App. 2021) (Choctaw Reservation); Grayson v. State, 485 P.3d 250 (Okla. Crim. App. 2021) (Seminole Nation); State v. Lawhorn, 499 P.2d 777 (Okla. Crim. App. 2021).

[8] See McGirt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452, 2459 (2020).

[9] See, e.g., Treaty With the Creeks, Art. XIV, March 24, 1832, 7 Stat. 366, 368; Treaty With the Creeks, preamble, Feb. 14, 1833, 7 Stat. 418.

[10] See, e.g., Treaty with Choctaw and Chickasaw, Apr. 28, 1866, 14 Stat. 769; Treaty with the Creek Indians, June 14, 1866, 14 Stat. 785.

[11] See Act of March 2, 1890, chap. 182, 26 Stat. 81.

[12] McGirt, 140 S. Ct. at 2475.

[13] See, e.g., U.S. v. Ramsey, 271 U.S. 467, 470 (1926).

[14] McGirt, 140 S. Ct. at 2463.

[15] See General Allotment Act, chap. 119, 24 Stat. 388 (1887). Heads of households received 160-acre allotments. Single individuals over the age of 18 and orphaned children received 80-acre allotments. Id.

[16] Id., §5, 24 Stat. at 389.

[17] Id., §6, 24 Stat. at 390.

[18] See id., §8, 24 Stat. at 391. It also did not apply to the Osage Nation, the Miami and Peoria Tribes nor the Sac and Fox Nation. The exception of the Five Tribes from the General Allotment Act stemmed from a belief that because the tribes owned their lands in fee, the federal government did not have the power to forcibly allot their lands. See McGirt, 140 S. Ct. at 2463.

[19] Ch. 517, 30 Stat. 495 (June 28, 1898). The Curtis Act abolished the tribal courts and threatened the forcible allotment of tribal lands unless the tribes voluntarily agreed to allot their lands.

[20] There were separate rolls for Indians by blood, intermarried white citizens and freedmen (descendants of African Americans enslaved by the tribes).

[21] See, e.g., Cherokee Allotment Agreement, chap. 1375, 32 Stat. 716 (July 1, 1902); Seminole Allotment Agreement, ch. 542, 30 Stat. 567 (July 1, 1898).

[22] The Supreme Court upheld Congress’s authority to impose these allotments in Tiger v. Western Investment Co., 221 U.S. 286, (1911).

[23] The state of Oklahoma removed the restrictions on many of these allotments shortly after Oklahoma became a state. In 1908, Congress eliminated all restrictions on the allotments of Indians with less than one-half degree of Indian blood, intermarried white citizens and freedmen. Act of May 27, 1908, chap. 199, 35 Stat. 312. Land also lost its restricted status if inherited by any Indian heirs less than full blood. Id., §9, 35 Stat. at 315. In 1947, Congress amended the law to provide that land lost its restricted status if inherited by anyone with less than one-half degree of Indian blood. See Act of Aug. 4, 1947, 61 Stat. 731. In 2018, Congress eliminated the minimum blood quantum requirement, and now, restricted land retains its status if inherited by anyone who is a lineal descendant of an original Five Tribes Indian allottee. See Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018); see also C. Cleary, “The Stigler Act Amendments of 2018,” 91 Okla. B. J. 50 (2020).

[24] Five Tribes Act, chap. 1876, 34 Stat. 137 (Apr. 26, 1906).

[25] Id., §11, 34 Stat. at 141.

[26] Id., §28, 34 Stat. at 148.

[27] Oklahoma Enabling Act, chap. 3335, 34 Stat. 267 (June 16, 1906).

[28] Tiger, 221 U.S. at 309.

[29] Oklahoma Enabling Act, §3, 34 Stat. at 270.

[30] Id., §1, 34 Stat. at 267-68.

[31] One exception was the Osage Reservation.

[32] See, e.g., Ellis v. Page, 351 F.2d 250 (10th Cir. 1965) (Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation); Tooisgah v. United States, 186 F.2d 93 (10th Cir. 1950) (Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation). Although not all allotment statutes result in disestablishment of the reservations, see McGirt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452, 2465 (2020), the courts in Ellis and Tooisgah concluded that the respective allotment statutes contained unambiguous language whereby the tribes unequivocally surrendered all tribal interests in the reservation lands.

[33] See Nowabbi, 61 P.2d at 1154 (“We think the obvious purpose of the final and explicit proviso of said act was to take the Indians in the Indian Territory out of the category of Reservation Indians. And it shows a clear and unmistakable intention on the part of Congress to limit the jurisdiction of the United States over allotments in the Indian Territory.”). Even leading Indian law scholars concluded there were no reservations in Oklahoma. See, e.g., F. Prucha, The Great Father 262 (abridged ed., 1986) (“The Indians of Oklahoma were an anomaly in Indian-white relations ... There are no Indian reservations in Oklahoma ... [T]he reservation experience that was fundamental for most Indian groups in the twentieth century was not part of Oklahoma Indian history.”).

[34] See McGirt, 140 S. Ct. at 2474 (“Unable to show that Congress disestablished the Creek Reservation, Oklahoma next tries to turn the tables in a completely different way. Now, it contends, Congress never established a reservation in the first place.”).

[35] U.S. v. Ramsey, 271 U.S. 467 (1926) (restricted Osage allotment); Ex Parte Nowabbi, 61 P.2d 1139, 1154 (Okla. Crim. App. 1936) (“[A]ll Indian allottees and their allotments in that part of the state of Oklahoma that was formerly Oklahoma Territory, are lands in the Indian country within the meaning of [the General Crimes Act] and subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States, until the issuance of fee-simple patents.”). Subsequent court decisions confused the matter, however, after the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that the state of Oklahoma had jurisdiction to prosecute serious crimes committed on these allotments notwithstanding the Major Crimes Act, which generally gives the federal government exclusive jurisdiction. See Tooisgah v. U.S., 186 F.2d 93 (10th Cir. 1950). In reality, the decision in Tooisgah was a narrow and limited one because, at the relevant time, the Major Crimes Act applied only “on and within an[ ] Indian reservation” as opposed to “Indian country,” which would include allotments. This conclusion was immediately limited to its facts since, by the time the decision was issued, Congress had amended the Major Crimes Act to apply to “Indian country” rather than just reservations and had enacted a definition of Indian country that expressly included reservations and allotments as separate and distinct categories of Indian country. See 18 U.S.C. §1151(a), (c). Unfortunately, subsequent court decisions interpreted Tooisgah as generally concluding that trust allotments were not considered “Indian country” and failed to take account of the intervening statutory definition of Indian country Congress enacted in 1948. See, e.g., Application of Yates, 349 P.2d 45 (Okla. Crim. App. 1960); Ellis v. State, 386 P.2d 326 (Okla. Crim. App. 1963).

[36] Ex Parte Nowabbi, 61 P.2d 1139 (Okla. Crim. App. 1936).

[37] Act of May 8, 1906, chap. 2348, 34 Stat. 182.

[38] Nowabbi, 61 P.2d at 1154 (“We think the obvious purpose of the final and explicit proviso of said act was to take the Indians in the Indian Territory out of the category of Reservation Indians. And it shows a clear and unmistakable intention on the part of Congress to limit the jurisdiction of the United States over allotments in the Indian Territory.”).

[39] Letter from Johnston Murray, governor of Oklahoma, to Orme Lewis, assistant secretary of the Interior (Nov. 18, 1953).

[40] 11 Okla. Op. Att’y. Gen. 345 (1979), available at 1979 WL 37653.

[41] Indian Reorganization Act, ch. 576, 48 Stat. 984. Congress extended the provisions of the Indian Reorganization Act to Oklahoma tribes in the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act, 49 Stat. 1967.

[42] 18 U.S.C. §1151(a)-(c).

[43] H.R. Con. Res. 108, 83d Cong. (Aug. 1, 1953) (Congress declared its intent “to make the Indians ... subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens” and “at the earliest possible time, all of the Indian tribes and the individual members ... should be freed from Federal supervision and control.”).

[44] In 1953, Gov. Murray issued a statement that “Public Law No. 280 will not in any way affect the Indian citizens of this State” because “[w]hen Oklahoma became a State, all tribal governments within its boundaries became merged in the State and ... came under State jurisdiction.”

[45] See, e.g., President Richard Nixon, Special Message to Congress, July 8, 1970.

[46] See Muscogee (Creek) Nation v. Hodel, 851 F.2d 1439 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (upholding power of tribe to reestablish its tribal courts); Harjo v. Kleppe, 420 F.Supp. 1110 (D.D.C. 1976), aff’d sub. nom, Harjo v. Andrus, 581 F.2d 949 (D.C. Cir. 1978) (upholding the legitimacy and authority of the Creek National Council).

[47] 573 P.2d 263 (Okla. Crim. App. 1978). The court clarified the confusion engendered by cases like Tooisgah and its progeny, see supra note 35, and definitively concluded that trust allotments in western Oklahoma remained Indian country. In support of its conclusion, it pointed to the failure of the state of Oklahoma to affirmatively assume jurisdiction over Indian country under Public Law 280. Id. at 265.

[48] 711 P.2d 77 (Okla. 1985).

[49] Id.

[50] 782 P.2d 401 (Okla. Crim. App. 1989).

[51] Cravatt v. State, 825 P.2d 277, 279 (Okla. Crim. App. 1992).

[52] 968 F.2d 1058 (10th Cir. 1992).

[53] See Ross v. Neff, 905 F.2d 1349 (10th Cir. 1990) (Cherokee trust land); Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes v. State of Oklahoma, 618 F.2d 665 (10th Cir. 1980). The 10th Circuit reached the same conclusion with respect to unallotted lands held in trust for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. See Indian Country, U.S.A., Inc. v. Oklahoma Tax Commission, 829 F.2d 967 (10th Cir. 1987). Pursuant to the Five Tribes Act of 1906, unallotted lands of the Five Tribes passed to the United States to be held in trust for their benefit. Id. (citing the Five Tribes Act of 1906, ch. 1876, §27, 34 Stat. 137, 148); cf. Choctaw Nation v. Oklahoma, 397 U.S. 620 (1970) (bed of the Arkansas River not allotted and therefore held in trust for the Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw nations).

[54] Okla. Tax Comm’n v. Citizen Band Potawatomi Tribe, 498 U.S. 505, 511 (1991).

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 94 Vol 5 (May 2023)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.