Oklahoma Bar Journal

The History and Impact of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation

By Renee DeMoss and Bob Burke

The land where the Oklahoma Bar Center stands today. Photograph used for a story in The Daily Oklahoman newspaper. “Above is the farm of W. F. Harn, lying southwest of the state Capitol and State Historical Society building. The 100-acre farm is the site of an oil field being started in defiance of city zoning regulations.” Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

The history of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation will always be intertwined with the history of the Oklahoma Bar Association and the dynamic evolution of the legal profession in Oklahoma.

The predecessor of the OBA was formed in 1904 when associations of attorneys in the separate Oklahoma and Indian territories merged. Membership in the group was voluntary. Those working as attorneys were not required to have any formal legal education. Many “read the law” by learning and observing in a law office or simply started taking on clients in the territories.

On the horizon was Oklahoma statehood. Attorneys were beginning to flex their muscles as Oklahoma became a state in 1907. A struggle emerged over who would control the practice of law in the new state. The Legislature was generally in charge, but several governors battled for the power to make rules on who was qualified to be a lawyer and how they would be disciplined for any wrongdoing.

In 1929, the Oklahoma Legislature took a major step to gain control of the practice of law by enacting a statute that created a formal attorney organization called the “State Bar of Oklahoma.” This required all attorneys to join as members to practice in the state. It established minimal educational requirements for licensed attorneys and created a “Board of Governors,” which had the authority to discipline attorneys, subject to the approval of the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

For the first two decades of statehood, constant public squabbling characterized the relationship between the bar and the judiciary. After the Legislature passed the 1929 law that created the State Bar of Oklahoma, Oklahoma Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles W. Mason seized the opportunity to take one final jab at the former voluntary bar for its behavior and criticism of judges:

The bar association of this state, prior to this time, has been a voluntary organization and while some good has been accomplished, the state conventions have been very largely social affairs. The lawyers have often come together, giving each other the glad hand, renewing old comradeships ... and that is about all that has been accomplished, except to give some lawyer who had recently lost a case an opportunity to cuss the court while his opposing counsel sat by and enjoyed his vilification and vituperation without uttering a word and little realizing that such procedure was eating out the very foundation of government itself by shaking the confidence of the uninformed layman in the judiciary.

In the 1930s, the Legislature tried to exert further influence over the bar by dictating who could be a lawyer. The 1937 Legislature passed a bill that permitted anyone who had served three terms in the Oklahoma Legislature to practice law, without requiring them to have either obtained a law school education or passed a bar exam. In vetoing the bill, Gov. E. W. Marland told legislative leaders, “I would be willing to sign such a bill if you also submit one providing that anyone who has had a venereal disease three times will be allowed to practice medicine.”

On Oct. 10, 1939, the Oklahoma Supreme Court finally took control. In the case of In re Integration of the Oklahoma State Bar, 185 Okla. 505, 506, 97 P.2d 113 (Okla. 1939), the court declared it, not the Legislature, had the inherent power to regulate Oklahoma lawyers. The court reasoned, “The very fact that the Supreme Court was created by the Constitution gives it the right to regulate the matter of who shall be admitted to practice law before the Supreme Court and inferior courts, and also gives it the right to regulate and control the practice of law within its jurisdiction.”

Now firmly under Supreme Court control, the fledgling OBA faced many challenges. A big problem was that the OBA had no place to call home. It was forced to rent space in an old, cramped office building in downtown Oklahoma City. It had no staff at all before the Supreme Court took control in 1939 and arranged for a small staff paid from bar association dues.

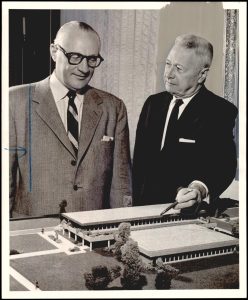

Photograph used for a story in the Oklahoma Times newspaper. “Proposed Headquarters, which the Oklahoma Bar Association possibly may build at N.E. 18th and Lincoln is shown in model form here by Gerald B. Klein, Tulsa, and J. T. Bailey, Cordell.” Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

This all changed when Gerald B. Klein of Tulsa was elected OBA president at the Annual Meeting in December 1945. Mr. Klein was not fazed by any of the problems; he had a plan. He also had the vision and passion to look ahead, lend a helping hand to other lawyers and keep the legal profession strong and trustworthy for the people of Oklahoma.

A PLACE TO CALL HOME

Mr. Klein’s first priority was finding a home for the association. His idea was to establish a separate organization that could fund and hold title to land for the OBA and construct a building on the land that would serve as a permanent home for Oklahoma lawyers. This entity would be the Oklahoma Bar Foundation.

Mr. Klein, however, did not limit his vision of what this separate entity could accomplish. He also wanted the foundation to engage in research and publication in fields of law important to Oklahoma and help provide access to justice for Oklahomans who could not afford attorneys.

Ultimately, leadership decided that a tax-exempt, nonprofit corporation should be formed to perform the work that lay ahead. On May 9, 1949, the Oklahoma Bar Foundation Inc. was formally incorporated. The OBF was granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service under section 501(c)(3) of the tax code. The Articles of Incorporation made all members of the OBA also members of the OBF and declared the purpose of the corporation to be for “educational, charitable and scientific purposes to advance the science of jurisprudence and promote the administration of justice.”

With the foundation up and running, the OBA and OBF moved forward with their plans to establish a permanent home for Oklahoma lawyers, known as the “Headquarters Project.” A building fund was created to raise money to purchase property for the project. After considering several locations, bar leaders selected the northwest corner of Northeast 18th Street and Lincoln Boulevard, part of the property known as the “Harn Tract,” just southwest of the state Capitol. After much negotiation, the land was purchased for $21,000.

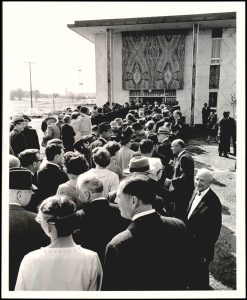

The first fundraising committee meeting for the Headquarters Project was held Jan. 7, 1959, at the J & J Café in Bristow. A pilot campaign proved a success, and the committee received $450,000 in donations for the project. On Sept. 21, 1962, the gleaming new 15,000-square-foot, $300,000 facility was proclaimed to be a symbol of the legal profession’s dedication to the public good.

A FIRM FINANCIAL FOOTING

Following the completion of the new building, the foundation continued supporting legal education projects and made sizeable awards to the University of Oklahoma, University of Tulsa and Oklahoma City University law schools. It provided financial assistance to establish the OBA’s Continuing Legal Education program, provided updates of bench materials for Oklahoma judges and funded other projects through donations it received from lawyers across the state.

The funding for legal education was strengthened in 1969 by two scholarships created by the OBF to honor renowned Oklahoma attorneys OBF founder Gerald A. Klein and Maurice Merrill, a beloved law professor who had a long and glorious career at the OU College of Law.

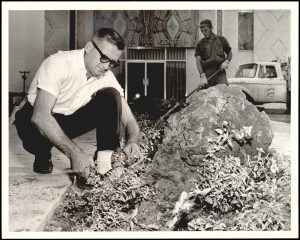

Photograph used for a story in the Oklahoma Times newspaper. “Putting shrubs in place Thursday for the Friday dedication of the Oklahoma Bar Center, south of the state Capitol, is Robert G. Burrows, left, landscape architect.” Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

As OBF Trustees set up these scholarships, accepted more donations and considered the future, they recognized the need to make sure the funds they received were adequately preserved, stating humorously:

The funds of the foundation are approaching the size when the services of volunteer money-managers, such as we who are trustees, will cost the foundation money because of our delay in investing, lack of knowledge of all available types of investment needed and lack of sophistication in what is a highly specialized business. Lawyers are notorious for looking after everyone’s money but their own.

An investment account was opened at Liberty Bank in Oklahoma City on Dec. 3, 1969.

The Trustees also realized they could not rely solely on irregular donations to pay for projects. Thankfully, a new infusion of funds came in the form of a charitable trust established by Tulsa philanthropist Leta McFarlin Chapman in 1969 and a later bequest to the OBF in her will. Through Ms. Chapman’s generous gifts, the OBF received $126,000 from payments made from the trust during her lifetime and $100,000 from her estate after she died in 1974.

Individual planned gifts like those of Ms. Chapman have proven to be a crucial factor in the foundation’s growth. The Chapman gift enabled the OBF to support legal education projects, such as its initial funding of the OBA Young Lawyers High School Mock Trial Program and its establishment of the Chapman-Rogers Education Fund, which, through interest earned from the careful investment of the $226,000 principal, currently provides a $2,500 scholarship every year to one student from each of Oklahoma’s three law schools.

Soon after this, OBF Trustees produced an idea to raise awareness of the foundation among Oklahoma attorneys and raise funds at the same time. In 1978, the OBF created the Fellows Program, now called the Partners for Justice Program, where an individual Oklahoma attorney makes a voluntary and sustained commitment to supporting the OBF in a specified dollar amount. The program was launched with 91 attorneys as founding Fellows.

When the OBF announced the program, OBF President Joe Stamper of Antlers recognized it would not only provide funds for legal charitable projects in Oklahoma but would also give attorneys a way to fulfill their professional responsibilities under the Oklahoma Rules of Professional Conduct. He said, “Many believe that lawyers have an inherent responsibility to give back to the community, and especially to provide legal services to the poor.” Being an OBF Partner was a way to do just that. Attorneys could fulfill their professional responsibilities knowing they would be making beneficial impacts on their communities.

Photograph used for a story in The Daily Oklahoman newspaper. “Hundreds of lawyers from all over the state were on hand for the official opening of the Oklahoma Bar Association's new $300,000 Bar Center on Lincoln Boulevard south of the state Capitol building.” Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

The year 1982 was pivotal for the foundation when the most imaginative idea for a new funding source arose, providing a new direction for OBF impact. OBA President John L. Boyd had attended a meeting of the Southern Conference of Bar Presidents and, while there, learned of a charitable funding program underway in Australia, Canada and Florida. It involved the money attorneys hold in trust for their clients called “IOLTA” for “Interest on Lawyer’s Trust Accounts.” IOLTA programs had generated extraordinary revenues for states such as Florida.

In April 1983, effective 1984, the Oklahoma Supreme Court authorized the OBF to establish the IOLTA program. Today, all 50 states, Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands operate charitable IOLTA programs.

Another new revenue source that had a significant impact presented itself through a substantial gift in 1982 from Mary Huntsman Howell. Ms. Howell was the widow of prominent Oklahoma City attorney Edward Howell, who died in 1966 after practicing law for 61 years. Ms. Howell included the OBF as a beneficiary in her estate, planning to honor her husband. She had developed an active interest in the OBF and its projects through her nephew, attorney Thomas C. Smith Jr., a well-respected lawyer and OBF Trustee, who often talked to her about the work Oklahoma lawyers were doing through the OBF. Ms. Howell left $500,000 to the foundation, specifying in her will that the funds should be invested and the income used to further the purposes of the foundation.

It was through receipt of this gift, designated the “Edward and Mary Howell Memorial Fund,” that the OBF Board of Trustees could really look to the future with renewed enthusiasm and resolve. James L. Sneed, Tulsa attorney and OBF president, said:

A gift of this magnitude is of immense importance to the Bar Foundation as it will enable the foundation to broaden the scope of its services to members of the legal profession, members of the judiciary and the public.

In January 1983, OBF President Winfrey Houston appointed a subcommittee to consider how to use the income from the Howell gift. They performed their work quickly, and on Feb. 21, 1983, they produced a report that contained an extensive list of potential projects for the foundation to undertake. In its report, the subcommittee reminded the board of the need to develop an ongoing fundraising program to accomplish its charitable goals:

There is a continual need for funds if we are going to have a viable, progressive program of the foundation ... Each of us needs to be conscious of the opportunities to help in funding the objectives and purposes that are available through the foundation. Such an effort must be a continuous effort, that needs to be well-coordinated and publicized.

OBF President Houston also appointed an investment subcommittee to ensure that the principle of the Howell gift was handled appropriately, and the foundation continued to carefully build and maintain its portfolio.

A huge moment for the foundation came in 1986 when the first IOLTA grants for nonprofit legal services were made. Up to that point, the OBF had supported a wide range of projects, but now, the foundation had a new direction. That first year, the OBF awarded IOLTA grants totaling $105,000 – including $32,874 to Legal Aid of Western Oklahoma Inc., $27,188 to Legal Services of Eastern Oklahoma Inc. and $15,000 to Oklahoma Indian Legal Services – to provide legal representation to Oklahomans in need. As OBF President John Boyd told the OBF board, “Until recently, the organization was in a state of metamorphosis. The foundation now has a purpose and should continue to grow.” Funds from the IOLTA program dedicated to providing legal representation to the poor gave the foundation a new and important way to make an impact.

GROWING NEEDS

Nancy L. Coats became the first woman to serve as president of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation in 1981.

The need for legal help in Oklahoma communities began to mount during the 1990s, with 1991 OBF President Terry Kern of Ardmore sounding the warning that “agencies serving the public in the legal arena are struggling to keep up with the ever-increasing caseloads of poverty level individuals.” The need for IOLTA grants was growing.

As the 1990s ended, it became clear that IOLTA remittals had been dwindling for years. An OBF financial report from 2000 noted that in the future, awards would have to be limited “due to the decline in income reflective of the current state of the economy and lower interest rates.” In 2002, $216,225 remittals were about one-third less than the 1998 $351,900 remittals, and 2003 remittals were predicted to be less than $200,000.

Other events converged to create concern, including the collapse of the dot-com bubble and the September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. Also, a series of accounting scandals at major U.S. corporations caused the economy to swing sharply downward. The OBF also had to face the fact that Oklahoma’s voluntary IOLTA program was underperforming. Oklahoma lagged far behind most other states in the number of accounts opened by attorneys and in the amount of interest financial institutions paid on those accounts.

The OBF’s fortunes began to change, however, when a 2003 U.S. Supreme Court decision put a halt to ongoing legal challenges that were preventing some attorneys from joining IOLTA. The court ruled in Brown v. Legal Foundation of Washington, 538 U.S. 216 (2003), that Washington state’s mandatory IOLTA program did not violate the Fifth Amendment by taking interest from IOLTA trust accounts. In the wake of this decision, the OBF petitioned the Oklahoma Supreme Court to make the program mandatory for all Oklahoma attorneys. The differences between voluntary and mandatory IOLTA programs were staggering. With only a voluntary program, Oklahoma fell to the bottom – 49th in the nation – in the amount of IOLTA funds the program generated per person in need in the state.

In June 2003, the Oklahoma Supreme Court approved changes to Rule 1.15 of the Oklahoma Rules of Professional Conduct to convert the IOLTA program from voluntary to mandatory for all attorneys, effective July 1, 2004.

For the first several years following the adoption of the mandatory program, the OBF saw IOLTA revenues soar, beginning with $476,287 in 2005, $770,557 in 2006 and a high of $1,003,634 in 2007. The 2007 remittal amount remains the most IOLTA income the OBF has ever received in a single year. Now, with the mandatory program in place, the OBF has been able to expand the number of programs supported and increase funding for nonprofits that provide legal representation to specific populations, such as abused children, elderly citizens and refugees. Both urban and rural Oklahoma areas received support from OBF grants.

In the mid-2000s, a new source of significant funding began to strengthen the OBF’s endowment and stretch its reach. This welcome development came in the form of cy pres awards. Cy pres awards are often made in class action cases when a suit is brought on behalf of a “class” of people who may have been harmed but who have not been specifically identified as plaintiffs in the lawsuit and would otherwise be unrepresented. Often, when a judgment is rendered or a settlement reached in such a case, many of the class members who were intended recipients cannot be paid because, for example, they cannot be located, so final surplus funds will remain from the action. Based on a court’s broad equitable powers and the cy pres doctrine, these surplus funds can be distributed to benefit others.

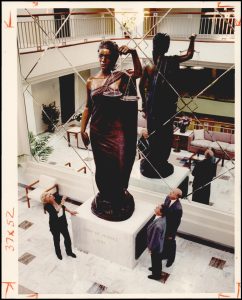

Sculptor Jo Saylors, OBA Executive Director Marvin C. Emerson and 1990 OBF President Jon H. Trudgeon discuss the “Lady of Justice” statue unveiled in the atrium of the Oklahoma Bar Center in June 1991. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

The first cy pres funds the OBF received were awarded in December 2006, stemming from the settlement of a class action case in Beaver County, Lobo Exploration Company v. BP American Production Company. The case was filed in 1997 and settled in 2006 for $150 million. The search for all class members entitled to recover funds began, but many had passed away during the years or could not be found.

Four days before Christmas in 2006, plaintiff’s attorney informed the Beaver County associate district judge of the parties’ agreement regarding the final $2 million in surplus funds that could not be awarded to the rightful owners. They agreed on a cy pres use. The funds would go to the Oklahoma Bar Foundation with “a portion of the proceeds earmarked and used to fund a grant program for the appellate and district courts.” Courts could submit applications for grants to pay for courthouse technology improvements, computer equipment and related items.

The cy pres court grant awards were a boon for the many ill-equipped county courthouses across the state that did not have the funds to address all of their basic technology needs. In the first four years of the new program, 25 courts throughout the state were awarded grants for various projects, including digital court reporting systems, sound equipment, audiovisual equipment for courtrooms and Wi-Fi capabilities.

Not long after the new court grant program was put in place, the effects of the 2008 Great Recession began to significantly harm the OBF’s ability to make grants. As 2009 progressed, the effects became more pronounced. Total IOLTA remittals plunged from a healthy $867,620 in 2008 to $377,251 in 2009. IOLTA receipts in 2010 and 2011 did not exceed $350,000 in either year. The year 2012 was especially difficult, with an 87% decline in IOLTA remittals since 2009 at $241,254. Drastic cuts were required, and legal service programs and communities across the state were reeling from the negative impact.

CHALLENGES OF A CHANGING WORLD

As the OBF struggled with the financial challenges, additional new challenges emerged – the need to keep up with technology was rapidly increasing along with the need for more funds for legal services. The number of people living in poverty by 2014 was at an all-time high. Once again, Oklahoma lawyers stepped up to the plate for the foundation and ushered in a new beginning designed to increase the ability to meet the funding demand. A new strategic plan was put in place, new foundation staff were hired, and updates were made in fundraising, technology and communications, with an eye toward making a bigger impact.

In 2015 and 2016, the OBF learned it would be receiving funds from class actions that had their genesis in the 2008 housing crisis and stock market crash. A settlement agreement in a lawsuit brought by the U.S. Department of Justice against Bank of America and its subsidiaries provided for an award of funds to organizations like IOLTA programs that make grants to provide civil legal services. The amount received by each IOLTA program was based on the individual state’s poverty level, and for Oklahoma, the amount was $4.1 million. These funds were earmarked for foreclosure defense work and community redevelopment programs designed to aid individuals in communities damaged by the housing market collapse.

Ultimately, the OBF made grants from the settlement funds in the program’s first year to more than 30 different programs in the amount of $1,366,600. These funds helped Oklahomans faced with many legal problems caused by the crisis, such as foreclosure, job loss, the inability to obtain employment and overcoming education barriers. To maximize and continue the impact, the remaining $3 million was invested to use as an ongoing source of annual OBF grants for mortgage foreclosure defense and community redevelopment projects.

The foundation continued to grow and make big strides until March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Normal activities ceased, and the foundation focused on helping its Grantee partners and their clients survive. One bright spot during the pandemic did appear in the form of another class action cy pres award to the foundation. The OBF received $500,000 from a Texas County case. The funds were to support grants that addressed the shortage of qualified court reporters working in Oklahoma, particularly in rural counties. Older reporters were retiring, and few new ones were graduating to take their places. Enrollment in court reporting schools was down, and those students who did attend, graduate and pass the certification exam were often lured by higher salaries in neighboring states like Texas and Kansas.

Two new types of grants were established. The first was educational block grants for qualified schools in the state to use for instruction. The second, court reporter employment grants, was designed to provide stipends for certain certified court reporters who agreed to work in rural courthouses. By the end of 2020, the OBF awarded $135,000 in grants to the three schools offering court reporting classes, and six educational grants have been awarded. Cy pres awards were continuing to expand the vision and impact of the OBF.

LOOKING FORWARD

The OBF belatedly celebrated its 75th year of existence in 2021, delayed due to the COVID pandemic. The goal of the celebration was to highlight how OBF donors and Grantees have made a difference in the lives of Oklahomans for more than 75 years through the provision of almost $19 million in grants and scholarships. The foundation is proud of the real-life stories explaining how OBF grants have been used to help solve the many different legal problems Oklahomans have faced through the years.

The OBF looks forward to continuing its work into 2023 and beyond. In October 2022, the Oklahoma Supreme Court approved amendments to ORPC 1.15, Safekeeping Property, to provide a process for implementing the rate comparability provision in the rule regarding the interest rates financial institutions pay on IOLTA accounts. It is anticipated that these procedural changes will increase the IOLTA remittals received on an annual basis and consequently increase the foundation’s ability to serve the people of Oklahoma through its mission to support legal services for the poor and vulnerable, law-related education and access to justice for all. The foundation’s essential purpose continues to advance the ongoing dynamic evolution of the legal profession in Oklahoma.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Renee DeMoss is the executive director of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation. She served as president of the OBF in 2008 and president of the OBA in 2014. Ms. DeMoss maintained a business litigation practice at GableGotwals in Tulsa for 35 years.

Bob Burke has been a workers' compensation and constitutional lawyer for 42 years. He is vice chair of the Oklahoma Supreme Court Committee on Judicial Elections and a Trustee of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation. Mr. Burke is a member of the Oklahoma Hall of Fame and has written more historical nonfiction books (154) than anyone in history.

Bob Burke has been a workers' compensation and constitutional lawyer for 42 years. He is vice chair of the Oklahoma Supreme Court Committee on Judicial Elections and a Trustee of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation. Mr. Burke is a member of the Oklahoma Hall of Fame and has written more historical nonfiction books (154) than anyone in history.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 94 Vol 5 (May 2023)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.