Oklahoma Bar Journal

The Evolution of Workers’ Compensation in Oklahoma

By Bob Burke

The first workers’ compensation laws in Oklahoma were unclear and confusing, only covering those in what the Legislature considered “hazardous employment.” Pictured above, workers posed with their wagons full of cotton in front of the Dulaney Cotton Gin in Cornish, Oklahoma. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

In the early years of the 20th century, injured workers in the United States exercised their common law rights to seek damages from a jury in a local court. As manufacturing jobs expanded, tort cases overburdened court dockets, and companies recognized the high cost of defending lawsuits – even if they prevailed. In addition, injured workers and their families often waited more than a year to receive any replacement wages or medical treatment.[1]

State legislatures heard from workers and employers. Business leaders in Oklahoma looked to Wisconsin, which passed a no-fault system in 1911, providing workers with quick medical care and reasonable compensation for lost wages in exchange for the workers giving up their right to sue their employer for negligence. It was known as the “industrial bargain” or the most common name, the “Grand Bargain.”[2]

A dozen states passed similar laws before Oklahoma vigorously debated and enacted its first workers’ compensation law in 1915.[3] When Gov. Robert L. Williams signed the bill, The Daily Oklahoman reported, “It compels the employer to protect his employees and at the same time relieves the employer of the burden of heavy and sometimes unreasonable damage suits in state courts.”[4]

The new law set up the State Industrial Commission to adjudicate claims of injured workers. However, the legislation did not provide benefits to spouses and children of workers killed on the job. That benefit would not be available for another 35 years. In 1950, voters amended the Oklahoma Constitution to allow the Legislature to provide for scheduled benefits to beneficiaries in work-related death cases.[5]

Before the ink was dry on the 1915 workers’ compensation law, there were cries of unconstitutionality. The Supreme Court of Oklahoma acted quickly and unanimously found the act constitutional within 16 months of its effective date.[6] It was in the 1917 opinion that the term “exclusive remedy” was used. Recognizing that the badly burned, injured worker would receive far less under the statutory scheme than in a tort suit with admitted negligence, the Supreme Court opined, “The compensation provided was intended to be exclusive, and a right of action in the courts therefore was abolished.”[7]

Six weeks after the Supreme Court of Oklahoma declared the Grand Bargain constitutional, the U. S. Supreme Court considered the issue in a case involving the New York workers’ compensation law. The high court upheld the legislative replacement of a common law tort with an exclusive remedy, no-fault statutory system with scheduled benefits for injured workers.[8]

New York Central Railroad held that state legislatures could provide a statutory system as an exclusive remedy for an injured worker’s claim against their employer. However, the justices mandated that the replacement of tort remedies must provide “significant” benefits. That term has been debated for a century.

THE HAZARDOUS EXPOSURE LIMITATION

Factory work was one of only two dozen occupations covered by the Industrial Commission’s jurisdiction as determined by the 1919 Oklahoma Legislature. Pictured above, employees produce clothing at an Oklahoma City garment factory. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

Unfortunately for both employers and injured workers, the first Oklahoma workers’ compensation law did not protect a majority of workers in the state. The law covered only workers in “hazardous employment.” There was no clear definition of the term, resulting in hundreds of legal challenges and legislative changes for the next half-century.

It was confusing at best. It was obvious from the statute that the Legislature intended to give the Industrial Commission latitude to determine what constituted “hazardous employment.” But the statute’s list of hazardous occupations allowed the Supreme Court to limit the jurisdiction of the commission and thus send claims to the district court. An early example was the Supreme Court’s denial of benefits to an employee of the Kingfisher County Highway Department who was injured in an automobile accident while driving to assist the county engineer with surveying a state highway. The Supreme Court said the worker was not engaged in “hazardous employment” because the injury did not fit within the “engineering works” category in the statute.[9]

The 1919 Legislature limited the jurisdiction of the Industrial Commission to injuries sustained in two dozen occupations, such as cotton gins, factories, logging, streetcars and oil refineries.[10] Still, the Supreme Court held that a single employer could have both hazardous and nonhazardous employees under the same roof. The Legislature occasionally tried to refine its definition of “hazardous employment,” but the Supreme Court still struggled to determine what injury fit the definition. The uncertainty often resulted in decisions that denied benefits for serious injuries obviously sustained in the course and scope of employment. A traveling salesman lost sight in one eye when he was struck by an object flying off a passing vehicle. The Supreme Court denied benefits because being a traveling salesman was not “manual labor.”[11]

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma consistently used the narrowest of statutory interpretations to overturn the Industrial Commission’s award of benefits to workers injured in what we today uniformly classify as hazardous. The problem grew worse as more Oklahoma workers were employed in occupations not covered by workers’ compensation. Thousands of workers were not provided benefits, even if they were clearly injured as a result of their employment.[12]

Occasionally, the Supreme Court ruled favorably for an injured worker in a case where the evidence was too close to call. In an early law, it was presumed that an injured worker should be awarded benefits as a matter of social policy if the evidence was equal. That presumption favoring the worker was eliminated from the law in 1999.[13]

Jurisdiction of workers’ compensation claims remained with the state Industrial Commission until 1959, when the Legislature created the State Industrial Court and made it a court of record in the judicial branch.

IN THE COURSE AND SCOPE OF EMPLOYMENT

The number one source of litigation in more than a century of interpreting Oklahoma’s workers’ compensation laws is the statutory requirement that an injury is compensable only if it arises out of the course of and in the scope of employment. The “in the course of” was generally interpreted to mean that a worker was covered by workers’ compensation if they were injured during a normal work activity. The “scope of employment” meant the accident must be due to the employment and must result from a risk reasonably incident to the employment.[14]

In 2000, Justice Yvonne Kauger explained the concept of an injury arising out of employment in the case of Turner v. B Sew Inn:[15]

To meet the “arising out of” test, it must appear to the rational mind, upon considering all the circumstances, that a causal connection exists between the conditions under which the work is to be performed and the resulting injury. ...

A NEW DIRECTION

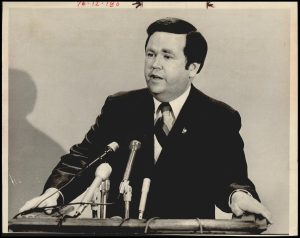

In the first 55 years of the Oklahoma workers’ compensation law, from 1915 to 1970, there were complaints that the “hazardous employment” doctrine was unfair because injuries to schoolteachers, retail workers and most government workers were not compensable. Legislators, employers and representatives of injured workers recognized the need for a more comprehensive statutory scheme. When David L. Boren was elected governor in 1974, he created a committee of legislators, business leaders and worker advocates to survey other states’ recent reforms.[16] After much debate and compromise, the Workers’ Compensation Act was passed by the 1977 Legislature.[17] A veteran newspaper reporter said the act was passed “after some of the longest legislative studies and conflicts in recent years.”[18]

After 55 years of the confusing “hazardous employment” requirement for workers’ compensation, 1975 Gov. David L. Boren, pictured above, put together a committee to reform the law. In 1977, the Workers’ Compensation Act was passed. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

The new law reversed the troublesome “hazardous occupation” requirement and placed most workers in the state, except for agricultural and domestic workers, under coverage for benefits. A new Workers’ Compensation Court was created. Its members would be appointed by the governor from a list provided by the Judicial Nominating Commission. Gov. Boren appointed Marian Opala, administrative director of the state court system, as presiding judge of the Industrial Court to make smooth the transition to the new court.[19]

In the 1980s and 1990s, there was a period of relative calm and stability. There were predictable ups and downs in the size of awards, depending upon whom the sitting governor appointed as judges. There was still a continuous effort to close loopholes or add components such as mediation and providing counselors to assist injured workers. In the 33 years from 1977 to 2010, the Legislature passed 19 changes to the Workers’ Compensation Act. Countless unsuccessful bills were presented because someone was unhappy with the result of a single case or line of cases.[20]

Employers’ immunity from tort claims was recognized for decades after the 1977 reform, except for an occasional deviation regarding an intentional tort. In 2005, the Supreme Court dealt a blow to the blanket exclusive remedy for employers in the case of Parret v. UNICCO Service Company.[21] The court adopted the “substantial certainty” standard, which meant that the narrow intentional tort exception to workers’ compensation exclusivity was available to an injured worker if the accident or death was substantially certain to occur.[22] Since Parret, the Legislature has attempted to eliminate most intentional torts. The appellate courts have weighed in on the subject, but it remains uncertain whether or not some intentional torts in a direct action in district court against the employer remain viable.

Another subject of reform in the early years of the current century regarded the rigid rule that allowed compensability of a mental injury only when accompanied by a physical injury. Occasionally, the rule resulted in a harsh decision. In Fenwick v. Oklahoma State Penitentiary,[23] benefits were denied to an employee of the state prison who was held hostage during a disturbance. He was released without physical injury but sustained a serious psychiatric injury. All agreed he was disabled, but the Supreme Court followed the statute. After other similar decisions, the Legislature eventually made an exception for mental-only injuries when an injury resulted from a rape or another crime of violence that arose out of and in the course of employment.[24]

DEMAND FOR DRASTIC CHANGE

Employers and the Oklahoma State Chamber of Commerce called for drastic changes in the workers’ compensation system in 2010 because of the belief that judges of the Workers’ Compensation Court made excessive awards for permanent partial disability (PPD). The state chamber cited statistics that showed the average PPD award rose from $13,176 in 2001 to $32,452 in 2010.[25]

One of the first acts of Gov. Mary Fallin when she assumed office in January 2011 was to appoint a working group to rewrite Title 85 to codify decades of appellate court decisions and strictly limit perceived abuses. The result was Senate Bill 878, which passed the state Senate 48-0 and the House of Representatives 88-8.[26]

Even though Gov. Fallin predicted the new Workers’ Compensation Code would save employers $30 million a year,[27] the law was never given a reasonable chance to succeed. A small group of companies began lobbying for additional changes. Months before the 2013 legislative session, The Oklahoman, the state’s largest newspaper, called for abolishing the Workers’ Compensation Court and creating an administrative system. Two large Oklahoma companies were out front: Hobby Lobby, the nationwide arts and crafts chain headquartered in Oklahoma City, and Unit Drilling, an oil and gas firm based in Tulsa. They believed the current system was broken and was a huge impediment to economic growth in the state.[28]

When the reform measure was introduced, I argued in an opinion piece published by The Oklahoman that the bill contained numerous unconstitutional provisions and that if the reform was enacted, Oklahoma would need two different systems for handling workers’ compensation claims for many years to come.[29]

Despite warnings, in the closing days of the 2013 legislative session, Senate Bill 1062 was passed and signed into law, effective Feb. 1, 2014. The Administrative Workers’ Compensation Act (AWCA) created a Workers’ Compensation Commission, an administrative agency in the executive branch, to handle claims for all injuries that occurred after the effective date of the AWCA.[30]

The new law was destined to save employers money because its provisions unquestionably gave Oklahoma the lowest benefits for injured workers in the nation.[31] Immediate challenges to the constitutionality of the AWCA were filed, especially the provisions that gave the commission ultimate appellate authority over cases decided previously by the Workers’ Compensation Court.

The Legislature’s attempt to have one agency handle all claims was shot down by a unanimous Supreme Court that held that “all aspects” of claims for injuries occurring prior to Feb. 1, 2014, must be adjudicated by the old court of record, renamed the Court of Existing Claims (CEC). As predicted, Oklahoma will have two workers’ compensation systems well into the future. In 2022, it was estimated by the clerk of the CEC that about 12,000 old law cases remain open.[32]

Since 2014, more than 120 challenges to the AWCA have been filed. To date, 68 provisions of the AWCA have been found to be unconstitutional, invalid or inoperable. One of the major opinions that resounded far beyond Oklahoma was the Supreme Court’s finding that “opt out,” the ability of an employer to withdraw from a statutory workers’ compensation system and develop its own benefit plan, was unconstitutional.[33]

The decision in Vasquez v. Dillard’s Inc.[34] caught the attention of the nation, especially in conservative states in the South, where Walmart and other large companies pushed opt-out. National Public Radio reported, “A campaign by some of America’s biggest companies to ‘opt out’ of state workers’ compensation, and write their own plans for dealing with injured workers, was dealt a major blow.”[35] David Torrey, a workers’ compensation judge in Pennsylvania and a nationally recognized expert in workers’ compensation, said, “Despite companies spending millions of dollars to promote the idea, opt out is dead because of the comprehensive opinion by the Supreme Court of Oklahoma.”[36] Since the Vasquez decision in 2016, no state legislature in the nation has attempted to enact an opt-out law.

Other cases decided by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in challenges to the AWCA were recognized as major decisions in the field of workers’ compensation in the United States. A unanimous decision in Torres v. Seaboard Foods, LLC,[37] was hailed by a national expert as the most important workers’ compensation opinion released by a state supreme court in 25 years.[38] Torres established the principle that any provision of a workers’ compensation statute that shifts the economic burden to the injured worker without a legitimate state interest is unconstitutional.[39]

Another important decision was in the case of Maxwell v. Sprint PCS.[40] In finding a provision of the AWCA to be a forfeiture of benefits, the Supreme Court said the Legislature’s attempt to further cut benefits “trampled” the due process rights of the injured worker. The decision also held that if an injured worker received an order for permanent disability, it was a property right worthy of due process protection.[41]

We are now 10 years beyond the legislative passage of the AWCA. The 2019 Legislature granted a modest increase in injured worker benefits and struck from the act several unconstitutional provisions yet to be tested. The benefit increase moved Oklahoma from 50th to 46th among the states.[42]

More legal challenges to provisions of the AWCA are pending in the Court of Civil Appeals and the Supreme Court. But the dual system of adjudicating claims of injured workers is running smoothly. Administrators, judges and staff of both the Workers’ Compensation Commission and the Court of Existing Claims work together to carry out their respective functions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bob Burke has been a workers' compensation and constitutional lawyer for 42 years. He is vice chair of the Oklahoma Supreme Court Committee on Judicial Elections and a Trustee of the Oklahoma Bar Foundation. Mr. Burke is a member of the Oklahoma Hall of Fame and has written more historical nonfiction books (154) than anyone in history.

ENDNOTES

[1] Alan Pierce, Workers’ Compensation in the United States: The First 100 Years, (March 14, 2011), https://bit.ly/3nMFaIW.

[2] Gregory P. Guyton, “A Brief History of Workers’ Compensation,” 1 Iowa Orthopedic Journal, p. 106-110 (1999).

[3] House Bill 106, codified as Okla. Sess. Laws, chap. 546, §1, p. 574 (1915), was known as the Workmen’s Compensation Law. Over the years, the term evolved from “workmen’s compensation” to “workers’ compensation.”

[4] The Daily Oklahoman, Oct. 15, 1915.

[5] The constitutional question approved became Art. 23, §7 of the state constitution.

[6] See Adams v. Iten Biscuit Co., 1917 OK 47, 162 P. 938.

[7] Id. ¶17.

[8] See New York Central Railroad Company v. White, 243 U.S. 188 (1917).

[9] See Board of Commissioners of Kingfisher County, et al, 1919 OK 239, 182 P. 897.

[10] Okla. Sess. Laws, ch. 14, §2, p. 14 (1919).

[11] See Russell Flour & Feed Co. v. Walker, 1931 OK 136, 298 P. 291.

[12] See Neal v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 1978 OK 47, 578 P.2d 1191.

[13] Senate Bill 872, Okla. Sess. Laws, ch. 420, §6 (1999).

[14] 1 Larson, Workmen’s Compensation Law 41 (1952).

[15] 2000 OK 97, 18 P.3d 1070.

[16] The Daily Oklahoman, Jan. 18, 1975.

[17] Okla. Sess. Laws, 1977, chap. 234, effective July 1, 1978.

[18] The Daily Oklahoman, May 27, 1977.

[19] Id., June 8, 1977.

[20] Id., May 15, 2010.

[21] 2005 OK 54, 127 P.3d 572.

[22] Id. ¶25-27.

[23] 1990 OK 47, 792 P.2d 60.

[24] 85 O.S. 2011 §308(10)(f).

[25] The Oklahoman, Jan. 15, 2011.

[26] The new law was named the Oklahoma Workers’ Compensation Code and took effect Aug. 26, 2011. It was the first major rewrite of the workers’ compensation law since 1977.

[27] The Oklahoman, Dec. 6, 2012.

[28] Press release, Jan. 8, 2013, Oklahoma Injury Benefit Coalition.

[29] The Oklahoman, April 14, 2013.

[30] SB 1062 was codified as Title 85A.

[31] Tulsa World, Sept. 10, 2015; Michael Clingman, “Oklahoma’s Workers’ Compensation Benefits, Lowest in the United States,” Sept. 8, 2015, press release, Oklahoma Coalition for Workers Rights.

[32] Carlock v. Workers’ Compensation Commission, 2014 OK 29, 324 P.3d 408.

[33] See Michael Grabell and Howard Berkes, “Inside Corporate America’s Campaign to Ditch Workers’ Compensation,” (Oct. 14, 2015), http://bit.ly/418xUpl.

[34] 2016 OK 89, 381 P.3d 768.

[35] www.npr.org, Feb. 27, 2016.

[36] Conversation with Judge Torrey in New Orleans at a meeting of the College of Workers’ Compensation Lawyers, March 18, 2017.

[37] 2016 OK 20, 373 P.3d 1097.

[38] Statement of attorney Alan Pierce of Salem, Massachusetts, April 3, 2016. At the time, Mr. Pierce was president of the Workers’ Injury Law & Advocacy Group, the largest and most prominent national association of lawyers representing injured workers.

[39] Torres, supra.

[40] 2016 OK 41, 369 P.3d 1079.

[41] Id.

[42] Bob Burke, “A Comparison of Workers’ Compensation Benefits,” a white paper submitted to the Oklahoma Legislature, May 1, 2019.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 94 Vol 5 (May 2023)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.