Oklahoma Bar Journal

Skinner v. Oklahoma: How Two McAlester Lawyers Derailed Criminal Sterilization in America and the U.S. Supreme Court Invented ‘Strict Scrutiny’ as a Result

By Michael J. Davis

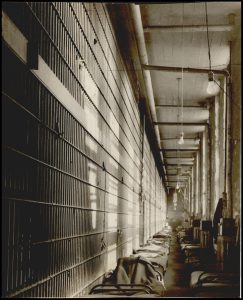

The law permitting criminal sterilization went into effect in 1935 while Skinner was serving time in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

In 1926, Jack T. Skinner stole 23 chickens.[1] This was the first in a line of felonies for which Skinner pleaded guilty and that eventually led to his alleged categorization as a “habitual criminal” under the Oklahoma Habitual Criminal Sterilization Act of 1935.[2] This law, argued by its author to be a nonpunitive civil statute, permitted forcible sterilization for individuals with three prior convictions of felonies involving moral turpitude.[3] Sterilization, in the words of Skinner’s attorney, Claud Briggs, was “the largest penalty that a red-blooded, virile young man could be required to pay.”[4]

After serving time for stealing chickens, Skinner was released from the Oklahoma State Reformatory in Granite and thereafter committed two separate armed robberies in 1929 and 1934.[5] While confined in the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester, the law permitting criminal sterilization went into effect under the signature of Gov. Ernest Whitworth Marland in 1935, taking such minor notice as to be buried on the 12th page of The Daily Oklahoman.[6]

A native of Shawnee, Skinner had been raised by a violent stepfather whom he ran away from home to escape. He was later the victim of a terrible accident that resulted in the loss of his left foot.[7] Court records show that his explanation for repetitive criminality related to the desperation of unemployment.[8] After his second armed robbery, in which he robbed a gas station clerk of $17 and was immediately arrested, his wife of that same year began divorce proceedings.[9] All of Skinner’s crimes were admitted by the defendant himself, and they all took place prior to the passage of the criminal sterilization statute.[10]

The state was a latecomer to criminal sterilization laws during this era, with most states preceding Oklahoma in passing some kind of criminal castration or sterilization statute, but this did not make the matter anodyne. When it became clear that the penitentiary rolls were being screened for possible sterilization candidates, the result at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in McAlester was chaos, riot, escape and shootouts.[11] Prisoners commandeered a vehicle by force, took guards as hostages and negotiated the opening of the front gates in broad daylight, eventually leading to a manhunt all the way to the outskirts of Antlers, where a farmer was taken hostage.[12]

Raising funds for legal representation from their meager prison labor earnings for the manufacturing of bricks and assembling of pillowcases, inmates at McAlester financially prepared for a protracted legal battle entirely on their own.[13] With advocates among the inmates hoisting signs that stated “Save Your Manhood,” prison canteen donations piled up to a reasonable sum over the preceding years.[14] Solicitation for representation to the American Civil Liberties Union was declined, as was a request for representation to famed attorney Clarence Darrow.[15] It fell to local representation, first by McAlester attorney Claude Briggs, to make a stand for the first inmate selected for sterilization surgery under the new law. That inmate, Hubert Moore, having escaped from the prison shortly after his selection, was quickly replaced by Skinner.

Claud Briggs had been a blacksmith and a farmer before embarking on a career in the law. Having never attended a law school, he came to the profession in an old-fashioned manner, taking the bar exam after a course of home study and then brilliantly receiving the second-highest score in the state as a result.[16]

The difficulties in representing Skinner may have seemed insurmountable at the time. The U.S. Supreme Court had already ruled on the constitutional legality of eugenic sterilization laws in the case of Buck v. Bell as a legitimate police power of the states, and the state of Oklahoma had already passed multiple eugenic sterilization laws prior to the 1935 version that now included the “habitual” criminal as a subject.[17] Prominent physicians and even criminologists lent some credibility to the prospect of sterilization for repeat offenders.[18] The law itself had been proposed and authored by Dr. Louis Henry Ritzhaupt in the state Legislature, and the famed criminologist Edwin Sutherland lent academic credence to the idea of sterilization of repeat offenders.[19]

Adding to the challenge, the Oklahoma Supreme Court had neutralized some of the most logical challenges to sterilization laws already by ruling that sterilization was not a punishment but merely a civil law aimed at community health and welfare.[20] This made an Eighth Amendment argument factually irrelevant. However, Claud Briggs was not merely a simple country lawyer; he was, by this point in his career, a member of the Oklahoma Senate and well-versed in the other possible rationales that could be used to challenge the statute.

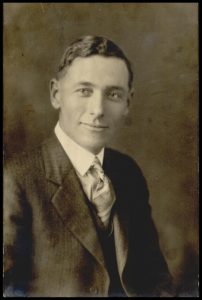

Claude Briggs, a McAlester attorney and Oklahoma senator, represented the defendant in Skinner v. Oklahoma. Courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society.

In an era when individual rights were not nearly as sacrosanct in constitutional law as perhaps they are today, deference was often given by courts to legislatures when individual welfare was pitted against the purported community interest.[21] The presumption of constitutionality was often maddeningly difficult for opponents of new laws to overcome, but courts were still nonetheless skeptical of arbitrariness in the design of such laws.[22] Briggs focused on the fact that the sterilization law was arbitrarily carved out for exemption offenses that seemed to be selected on the basis of class. The exemptions included “offenses arising out of violations of prohibitory laws, revenue acts, embezzlement, or political offenses” – quite neatly carving out a slew of white-collar crimes generally committed by those with more wealth, influence and power.[23]

Briggs, in a tour de force, made efforts to highlight other discrepancies at the initial civil hearing for Skinner’s selection for sterilization. When Dr. Ritzhaupt took the witness stand, Briggs was able to use his cross-examination as an opportunity for exposition: He entered into the record that despite the doctor’s insistence that criminal tendencies were inherited, of the 2,034 inmates at McAlester, only 12 had parents or grandparents who were offenders; for those 1,753 inmates who had served two or more terms in the corrections system, there was “not a single instance” when a parent had ever been convicted.[24] When Dr. D.W. Griffin (whose name later would adorn the Griffin Memorial Hospital in Norman) took the stand in favor of the law, Briggs was able to lure him to admit that criminality and Skinner’s own deviancy was “probably” more the result of poor socialization than a genetic inheritance.[25] Seeing the broader picture and the exploitability of a sterilization regime for even more malevolent purposes, Briggs’ closing argument in the hearing was a warning that if the Legislature has civil power to permanently and forcibly take procreative power from a convicted felon, the same such power could be used in a broader manner less palatable to the public.[26] He also warned that the unforeseen consequences may simply be to enflame rather than quell criminality.[27] Almost in prophetic coincidence, on the same day of the hearing, another six inmates escaped an Oklahoma correctional facility for fear of the sterilization law.[28] Skinner lost the hearing, and the case moved on as an appeal to the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

Knowing that public sentiment was slowly changing on the matter of eugenics – largely because of news coverage from Europe, where the Third Reich was beginning to pursue sterilization procedures on a massive scale – Briggs used his status as a legislator to stall further consideration and request a delay in the submittal of appellate briefs. When the matter could be stalled no further, his brief was a laundry list of potential rationales for reversal.[29] He argued the obvious: cruel and unusual punishment and inadequate due process. He also argued the less obvious but potentially grittier and interesting rationales, including that the sterilization statute was essentially an ex post facto law considering that Skinner had already been convicted prior to the law’s passage. But one argument stood out in particular, even if the Oklahoma Supreme Court later dismissed its merits: the idea that Skinner’s 14th Amendment entitlement to equal protection had been infringed.

In a stroke of luck, the Oklahoma Supreme Court took more than two years to rule against Skinner. The delay further permitted skepticism of eugenic intentions to permeate into American society as war consumed Europe and further details of Aryan purity campaigns came to light.[30] These intervening years permitted Americans to learn that Germany’s 1933 eugenics law had been utilized far more broadly than anticipated, with more than 400,000 Europeans having been sterilized by force in a number of “hereditary health courts” with deprivation of due process.[31]

For the final appeal, it was now time for a new attorney, one with experience in the U.S. Supreme Court, to take up responsibility for the case and navigate it to a conclusion before the highest court in the land. Guy Andrews, like Claud Briggs, was also from McAlester, a prominent attorney in the state and came to the practice of law from hardscrabble roots. Formerly a schoolteacher in Texas and later a coal mining superintendent in the small Pittsburg County town of Haileyville, he had never attended a law school but made his way to the halls of justice the old-fashioned way.[32]

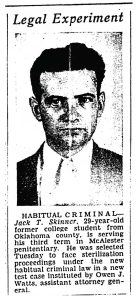

Jack Skinner’s classification as a “habitual criminal” led to him being the second Oklahoma inmate selected for sterilization surgery. Courtesy of The Oklahoman.

In his petition for a writ of certiorari, Andrews sunk his teeth into the equal protection argument wholesale and with a sense for rhetoric. In his words, “The terms of the Act exclude from its penalties the Capones, the Ponzis, and the Benedict Arnolds.”[33] Andrews went further, arguing the law created an “aristocracy of crime” that relieved a favored class for their crimes but stripped the “less fortunate” of their procreation abilities for similar bad acts.[34] It is perhaps a disappointing note for history that because of the meager funds for Skinner’s advocacy, Andrews had to agree for the case to be argued on the briefs instead of by personal appearance.[35] Despite this, the court determined to require the Oklahoma attorney general, Mac Q. Williamson, to appear to defend the law. In an argument before the court, Justice Frankfurter forcefully challenged Williamson to explain why “stealing chickens was included and embezzlement excluded.”[36] It took the U.S. Supreme Court just a few weeks to render a unanimous opinion.[37]

In discussing the inequalities of the Oklahoma law, Justice Douglas’ opinion outlined that a clerk who appropriates from their employer has committed the felony of embezzlement, a crime of moral turpitude by any reasonable standard.[38] And yet, as written, individuals committing such a crime many times would nonetheless be exempted from any potential sterilization penalty.[39] Simultaneously, any individual committing grand larceny twice for the same amount of money as the embezzlement and the same unjust enrichment would face the specter of a vasectomy or salpingectomy (removal of a fallopian tube) from a physician’s blade.[40]

While the court did not specifically overturn Buck v. Bell and therefore left the prospect of sterilization a potentially constitutional act, the opinion by Justice Douglas was sweeping enough to wipe away much desire by legislatures to continue moving in the direction of criminal offender sterilization by ruling in Skinner’s favor.

In an era when individual rights were not prioritized in the language of many judicial opinions, a new standard was articulated for the very first time: the concept of “strict scrutiny” for a statute that may unequally burden individual interests and potentially infringe upon a constitutional right. Previewed as a possibility in Justice Harlan Stone’s famous footnote 4 in United States v. Caroline Products Co., the idea of a “narrower scope” for judicial review had never been given the name “strict scrutiny” until Skinner.[41] Perhaps Justice Douglas did not even know it, but he had opened the door to a progeny of case law that would lead all the way to Brown v. Board of Education and beyond.

Before his death in 1977, Skinner had six grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren, and he had committed no further crimes.[42]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael J. Davis is an assistant professor of criminal justice at Southeastern Oklahoma State University, where he also serves as special assistant to the president for Compliance. Mr. Davis recently completed a three-year term on the OBA Board of Governors (2020-2022) and currently serves on the MCLE Commission.

ENDNOTES

[1] Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535, 539 (1942).

[2] Id.

[3] Transcript, Oklahoma v. Skinner, Okla. Pitts. Co. Dist. Ct. No. 15734 (1936) at 53.

[4] Id. at 161.

[5] Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535, 537 (1942).

[6] “Eugenics Law Revisited,” The Daily Oklahoman (May 16, 1935) at 12.

[7] Transcript, Oklahoma v. Skinner, Okla. Pitts. Co. Dist. Ct. No. 15734 (1936) at 100.

[8] Id. at 125.

[9] Victoria F. Nourse, In Reckless Hands: Skinner v. Oklahoma and the Near Triumph of American Eugenics 92 (2008).

[10] Id.

[11] “Posses Fear for Captive Guards,” The Daily Oklahoman (May 14, 1936) at 1.

[12] “Posse Pushes Hunt for Pair Near Antlers,” The Daily Oklahoman (May 15, 1936) at 1.

[13] “Briggs Plans to Fight on Law,” The Daily Oklahoman (May 20, 1936) at 2.

[14] “More About Sterilization,” The Oklahoma News (May 11, 1934) at 1.

[15] Victoria F. Nourse, In Reckless Hands: Skinner v. Oklahoma and the Near Triumph of American Eugenics 56 and 74 (2008).

[16] Id. at 41.

[17] Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

[18] Harry H. Laughlin, Eugenical Sterilization in the United States (1922).

[19] 1935 Okla. Sess. Laws, ch. 26 at 94-99; Edwin H. Sutherland, Criminology, 622 (1924).

[20] In re Main, 19 P.2d 153, 156 (1933).

[21] “The Presumption of Constitutionality,” 31 Colum. L. Rev. 7 (1931).

[22] Id.

[23] Okla. Senate Journal, 15th Legis. At 489-90 (Feb. 18, 1935); Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535, 537 (1942).

[24] Transcript, Oklahoma v. Skinner, Okla. Pitts. Co. Dist. Ct. No. 15734 (1936) at 55-56.

[25] Id. at 99-100.

[26] Id. at 160-165.

[27] Id. at 166-167.

[28] “Six Escape Prison as Jury Decides on Sterilization,” Tulsa Daily World (Oct. 21, 1936).

[29] Petition, Okla. Sup. Ct. No. 28229 (Oct. 27, 1937).

[30] Lawrence A. Zeidman, Brain Science Under the Swastika (2020).

[31] Id.

[32] 3 Joseph H. Thoburn, A Standard History of Oklahoma 1060 (1st. ed. 1916).

[33] Skinner v. Oklahoma, Petition for Writ of Certiorari, LSCT N. 782, at 23 (Dec. 4, 1941).

[34] Id. at 10-11.

[35] Victoria F. Nourse, In Reckless Hands: Skinner v. Oklahoma and the Near Triumph of American Eugenics 141 (2008).

[36] “Court Curious About State’s Sterilizing Law,” The Daily Oklahoman 15 (May 7, 1942).

[37] Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535 (1942).

[38] Id. at 538.

[39] Id. at 539.

[40] Id.

[41] United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152 n.4 (1938); Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson, 316 U.S. 535, 141 (1942).

[42] Victoria F. Nourse, In Reckless Hands: Skinner v. Oklahoma and the Near Triumph of American Eugenics 160 (2008).

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 94 Vol 5 (May 2023)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.