Oklahoma Bar Journal

'As Soon As' Three Simple Words That Crumbled Graduate School Segregation: Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents

By Cheryl Brown Wattley

Cheryl Brown Wattley

It was only a single page per curiam opinion issued by the United States Supreme Court in Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents.1 The pronouncement of Sipuel’s rights were contained in a single paragraph:

The petitioner is entitled to secure legal education afforded by a state institution. To this time, it has been denied her although during the same period many white applicants have been afforded legal education by the State. The State must provide it for her in conformity with the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and provide it as soon as it does for applicants of any other group.

It was a deliberately crafted order that avoided any constitutional pronouncement ending segregation in graduate education. It was an order that gave the state of Oklahoma sufficient ambiguity and opportunity to go through the pretextual motions of establishing a law school within just days that could be farcically heralded as “substantially equal” to the then 40-year-old University of Oklahoma College of Law. It was an order that caused the legal battle to gain Ada Lois Sipuel admission to the OU College of Law [hereinafter OU law school] to continue for yet another year and a half.2

At the same time, it was a ruling that reached beyond the territorial boundaries of Oklahoma and touched all states with segregated graduate education programs. It was an edict that furthered the disintegration of the fiction of separate but equal education and helped to pave the precedential pathway to Brown v. Board of Education. It crushed states’ arguments that African American citizens desiring to pursue graduate studies had to give advance notice to allow the state time to create a separate educational institution. It denied states of the evasive and obstructionist tactic of pleading for time to fund and establish alternate educational offerings for its African American citizens.

OU Rally | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

The Supreme Court’s frustration with state antics and delays was foretold by the questions posed to the attorneys representing Oklahoma in the oral argument before the Supreme Court. Maurice Merrill, acting dean of the OU law school and one of the state’s attorneys, was immediately asked questions. Justice Robert Jackson began:

"The state has known for two years she wanted to go to law school. What steps has the state taken? […] Not one step. We are one of 17 states with a public policy of segregation. We feel Miss Sipuel is not willing to recognize that policy.” Justice Jackson’s response, “a scorching rejoinder, […] ‘[w]hy should she be required to abide by anything more than a white person? Why should she be called upon to waive her constitutional rights?”3

“What if the Board of Regents decided to set up a separate law school for black students, what type of legal education would that provide?” Merrill provided his opinion that such a school would be more like studying in the lawyer’s office. The faculty would most likely not be very large. It would certainly be different from the education at the University of Oklahoma law school. … “If we were to issue an order that [Miss Sipuel] be admitted to the law school this coming semester, can the state do that, will the state do that?” Merrill, as the attorney for the state and as the acting dean of the law school, answered simply “yes.”4

Based upon the representations made at oral argument, the Supreme Court could have expected its order would cause Sipuel’s immediate admission to the OU law school. Just weeks earlier, Oklahoma officials had declined to establish a separate law school because funding was not available. That decision was made despite the impending Supreme Court argument and the express opinion of counsel that such a step would improve the state’s position before the Supreme Court.5Based upon that position, the only way for the state to provide Sipuel with a legal education “as soon as” it was afforded to white citizens would require her admission to the OU law school.

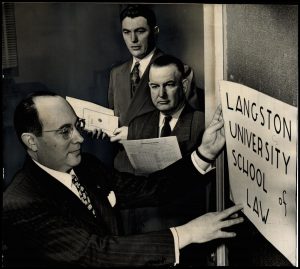

Instead, the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education passed a resolution on Jan. 19, 1948, that established the Langston School of Law and declared that it “shall be substantially equal to the course of study” at the OU law school.6 Predictably, when white students started classes at OU just a mere seven days later, on Jan. 26, 1948, Sipuel was again denied admission. This time, however, the denial was based upon the assertion that a “substantially equal law school” now existed for African American students: Langston School of Law.

The Langston School of Law consisted of three rooms rented in the state Capitol, including a classroom that was a converted storage closet. Resolutions were passed adopting the OU law school bulletin and course descriptions. An agreement was made that Langston Law School students would be allowed access to the state Capitol law library. A part-time dean and two part-time professors had been hastily hired.

Langston University | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

The Oklahoma Board of Bar Examiners issued a letter affirming that graduates of the law school would be eligible to sit for the Oklahoma bar exam. All of this was funded by an emergency gubernatorial allocation of $15,000 – money that had not been available just a few weeks earlier.7

Despite telegrams notifying her to enroll, Sipuel refused to attend Langston School of Law. Instead, she applied again to the OU law school and continued her legal battle with the state. A trial was held in May 1948 to determine whether the newly established Langston School of Law with its part-time faculty, rented rooms in the Oklahoma Capitol and no students was substantially equal to OU law school with its highly respected, full-time faculty, established physical facility and robust student body and alumni base. The NAACP called expert witnesses from across the nation, including the deans of Harvard Law School, University of Pennsylvania Law School, Boalt Hall Law School, University of Chicago School of Law and OU, who testified that Langston School of Law was not substantially equal to OU. Despite that testimony, Cleveland County District Judge Justin Henshaw found the rejection of Sipuel’s application was “legal and proper” and not a denial of the 14th Amendment because the state “had made available to [Sipuel] at the school of law of Langston University a course of instruction for first year law students which offered advantages for legal education substantially equal” to OU.8

But while Oklahoma was building its sham law school and defending it in court, other states were assessing the impact of the order on their educational systems.9 The University of Delaware Board of Trustees unanimously adopted a resolution directing the admission of any qualified Black student for a course of study that was not offered at the segregated school. The resolution was based upon the binding effect of the rulings in Sipuel and Gaines. As a result, Benjamin C. Whitten was admitted to the University of Delaware.10

On Jan. 30, 1948, University of Arkansas officials announced that African Americans would be admitted to graduate and professional schools. Silas Hunt filed an application and was subsequently admitted.11 The Alabama State Board of Education was ordered to assess the impact of the Sipuel order.12 In Georgia, the Board of Regents called upon university educational officials to study the impact of the order.13

The “as soon as” mandate was felt most sharply when six African American students applied on the last day of registration for the spring 1948 semester to graduate programs offered at OU. Roscoe Dunjee, head of the Oklahoma NAACP and publisher of The Black Dispatch, had recruited these students and strategically waited until the state would not have time to create yet another bogus course of study. The applicants sought immediate admission to graduate programs in social work, commercial education, architectural engineering, school administration and zoology.14 Dr. George Lynn Cross, OU’s president, had been instructed to request an opinion letter from Mac Williamson, the state attorney general, if any African American residents applied to OU. Williamson, in an astounding interpretation, informed Dr. Cross the applicants were not to be admitted; they had not given the state notice of their interest to study their respective fields. Based upon the attorney general’s opinion, all six applicants were denied admission.

But this time, litigation would not take years to secure the admission of the six applicants. Filing a lawsuit in Oklahoma federal court on behalf of Dr. George McLaurin, the NAACP argued the per curiam opinion in Sipuel demanded his immediate admission. It was an argument that resonated with the three-member panel of federal judges.

‘The State must provide it [legal education] for Sipuel … and provide it as soon as it does for applicants of any other group.’ To me that is unmistakably plain. I can consider that statement in the context of what I consider a living law. They are entitled to it before they are too old to receive it. [Under the criterion read into the decision by the attorney general] the state would be entitled to two years on the application of any Negro. I question whether a delay of two years affords the equal protection of the law. If that is true the fourteenth amendment is a farce.15

Fisher signing the Registrar | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

“As soon as.” “Unmistakably plain.” The panel ultimately issued its opinion. “We hold, in conformity with the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, that the plaintiff is entitled to secure a postgraduate course of study in education leading to a doctor’s degree in this State in a State institution, and that he is entitled to secure it as soon as it is afforded to any other applicant.”16 Within weeks, Dr. George McLaurin became the first African American to enroll in and attend the University of Oklahoma.

Before the one-page per curiam decision, only one court order had led to the admission and enrollment of an African American student. In 1936, the Maryland Court of Appeals ordered that Donald Murray be admitted to the University of Maryland School of Law.17 In the intervening 12 years, despite lawsuits filed by the NAACP, no other Black students had been ordered admitted to a segregated graduate program.18

This mandate of “as soon as” in the Sipuel decision changed that reality because states could not financially afford to maintain dual systems of graduate education. Those words caused the admission of Black graduate students in schools across the South, in Oklahoma, Arkansas and Delaware.

OU Class | Photo courtesy of the Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries, OU 1163B

They forced the Oklahoma Legislature to amend its statutes to allow the education of African Americans at state-supported institutions, albeit on a segregated basis. They were the first paving stones in a path that led to the matriculation and graduation of trailblazers, such as former Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Tom Colbert, Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals Judge David Lewis, former OU Regent Melvin Hall and countless other African Americans now practicing law.

Those three words caused, as Sipuel described in her autobiography, “the University of Oklahoma [to] come a long way … thousands of African Americans have attended, graduated from, and excelled at the University of Oklahoma. They have also done that at every public college in every southern state.”19 They did not lead to her immediate admission, but they financially crippled segregated systems of education and served to crumble the walls of segregated graduate education, a key steppingstone to Brown v. Board of Education.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cheryl Brown Wattley has practiced law for over 40 years. In 2006, she went into teaching at the OU College of Law and while there, wrote an award-winning book, A Step Toward Brown v. Board of Education: Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher and Her Fight to End Segregation. In 2014, she returned to Dallas as a founding faculty at UNT Dallas College of Law, where she continues to teach.

- Ada Lois Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631 (1948).

- Ada Lois Sipuel was finally admitted to the OU law school on June 20, 1949. Despite Sipuel’s refusal to enroll and the absence of any other students, Oklahoma had kept Langston School of Law open from January 1948 through June 1949. Once Langston’s closure was definite, Sipuel was admitted to OU because the state no longer offered a course of legal study in a separate institution.

- “NAACP Wins: O.U. Ordered to Admit Miss Sipuel,” The Black Dispatch, Jan. 17, 1948, 1, 2.

- Id.

- State officials had twice decided that the Oklahoma state budget could not provide funding for a separate law school for African American students. The Board of Regents for Higher Education met just weeks before the Supreme Court oral argument; however, it declined to take any action to establish a separate law school. Minutes, Board of Regents for Higher Education, 66th Meeting, Dec. 15, 1947, p. 508.

- Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, Resolution No. 142, Jan. 19, 1948. This declaration blatantly ignored the reality that Langston University, the state university for African Americans, had not been able to achieve accreditation by the North Central Association of Colleges. The accrediting agency informed state officials that, “Langston University has not at this time sufficient strength to justify approval of a program which includes graduate work.” W.D. Little, A Memorandum by Mr. W.D. Little, undated, Papers of George Lynn Cross, 12.

- Minutes of First Meeting, Regents’ Committee on Langston University School of Law, Jan. 19, 1948; Certificate, Board of Bar Examiners, Feb. 2, 1948; Certificate of Authority No. 9, Office of the Governor, State of Oklahoma, Jan. 22, 1948.

- Ada Lois Sipuel No. 14807, Transcript of Oral Proceedings, May 24, 1948; Minute of the Court, Sipuel v. Board of Regents, No: 14807, Aug. 2, 1948

- Henry Foster, an OU College of Law professor, testified at the evidentiary hearing about Langston School of Law and whether it was “substantially equal” to OU law school. Foster testified that Langston was “a fake, it is a fraud, and it is a deception, and to my mind [it] is an attempt to avoid the clear-cut mandate and orders of the Supreme Court of the United States. It is indecent.” Ada Lois Sipuel No. 14807, Transcript of Oral Proceedings, May 24, 1948, 141.

- Parker v. University of Delaware, 75 A.2d 225 (1950).

- Judith Kilpatrick, Desegregating the University of Arkansas School of Law: L. Clifford Davis and the Six Pioneers, The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 2 (summer 2009).

- “Alabama Makes Training Plans for Professions,” New Journal and Guide, Jan. 24, 1948, p. 9A.

- “Oklahoma Court Order Hits White Students,” The Chicago Defender, Jan. 24, 1948, p.1.

- Attorney General Mac Q. Williamson letter to Dr. G. L. Cross, President, University of Oklahoma, Jan. 29, 1948.

- OU Regents Minutes, Jan. 29, 1948, 2589-2596.

- McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, (W.D. Okla. 1948).

- Murray v. Pearson, 169 Md. 478 (1936).

- State of Tennessee ex. rel. Joseph M. Michael v. Henry B. Witham et al. Dec. 4, 1941; Bluford v. Canada, 32 F. Supp. 707 (D.C. Mo 1940); Affidavit of Charles L. Eubanks, Jan. 18, 1945, NAACP Papers, Part 3, Reel 11:1120.

- Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, A Matter of Black and White: The Autobiography of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, p. 185.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 92 Vol 5 (May 2021)