Oklahoma Bar Journal

Oklahoma's Embrace of the White Racial Identity

By Danne L. Johnson and Pamela Juarez

Danne Johnson

Pamela Juarez

The land that is now Oklahoma was added to the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which forced the Eastern Woodlands Indian tribes from their homelands and into “Indian Territory,” an area that eventually became Oklahoma, the journey, is known as the “Trail of Tears.” Simultaneously, the demand for ranching and pasture lands began to increase, and the government eventually opened the Indian Territory to settlement. This opening is commonly known as the “land run.” Oklahoma became the 46th state in 1907, following several acts that incorporated more and more Indian Territory into the United States. Oklahoma became a center for oil production, with much of the state’s early growth coming from that industry. During the 1930s, Oklahoma suffered from droughts and high winds, destroying farms and creating the infamous Dust Bowl of the Great Depression era. So goes the story of Oklahoma.

This common recitation of Oklahoma’s early history is void of the stories of how popular theories of manifest destiny guided efforts to colonize the people on the land and establish white supremacy.1 Indigenous people lived on and utilized the land and resources of what was to become Indian Territory before Oklahoma would be established. The indigenous people were from numerous tribes, each having a unique culture and way of life. As a result of the Louisiana Purchase, these lands became a part of the United States’ westward expansion.

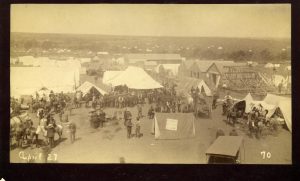

Land Run | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

Anti-Blackness and discrimination were not created in Oklahoma, rather they arrived with people, “new white” Americans and indigenous people from the southern states, who had learned, observed, practiced and sought to perfect white supremacy or other forms of control in the territory destined to become Oklahoma.

Racial whiteness was developed in the U.S. colonies in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Prior to that time, white was not a unifying identity. Laws differentiating jobs and rights in accordance with white as a racial identity came into existence during that time. Low- and no-wage laborers were separated by race, with European laborers accorded white skin privileges and certain benefits while free or indentured Africans, their descendants and other laborers were subjected to more restrictive laws and harsher punishments. Even with white skin privileges, European laborers experienced limited social mobility; however, the skin color hierarchical system prevented the low- and no-wage laborers from uniting across their skin color differences to combat the challenges presented in the new economy. Over time, these policies created a white identity that prevented white tradesmen from educating nonwhites.

We Are Americans Too | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

During the 1800s, white identity was strengthened through minstrel shows and negative literary portrayals of Africans and their descendants.2 The character traits of newness, cleanliness and rugged individuality defined the new white identity and stood in contrast to Africans, their descendants and other nonwhites who were generally cast as lazy, highly sexualized, communal, dishonest, dirty, dumb and sinister.

The benefits and privileges accorded to the newly created white racial identity can be examined through the experience of Irish immigrants in the late 1800s. The Irish, Africans and African descendants lived and worked in common areas in the northern United States. It is theorized the term “mulatto” appears in the 1850 census for the first time due to Irish and African or African descendant intermixing. In addition, there is a rich body of literature that supports the unity and camaraderie between those two communities initially.3 However, by the late 1800s, the Irish struggled to take on and assert a new white identity for job security and status. These efforts involved discriminating against their former friends and failing to support the causes that once united them. The Irish distanced themselves from Africans and African descendants by siding with anti-abolitionists and joining white supremacists. A similar homogenization process was experienced by other European ethnic minorities as they sought their fortune in the U.S. These European ethnic minorities gave up their traditional foods, dress and culture to adopt a “whiter” version of themselves.

As southern whites clamored for more land, the government acted to forcibly remove the indigenous people. In 1830, free Africans and free African descendants, enslaved Africans and enslaved African descendants traveling with indigenous owners, neighbors and relatives from Georgia, Florida and Mississippi arrived in Oklahoma as part of the Indian Removal Act. The Indian Removal Act was applied to the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek and Seminole tribes. It is estimated that 10-18% of each impacted tribe’s population was enslaved Africans and enslaved African descendants. It is estimated in 1861 there were more than 8,000 enslaved Africans and enslaved African descendants in Indian Territory, an estimate of free Africans and free African descendants is unavailable.

Numerous accounts trace indigenous ownership of Africans and African descendants to the encouragement by nonindigenous people in the southernmost states. As with the institution of slavery in most of the U.S., slave ownership was concentrated in the hands of a small number of wealthy farmers. Accounts of the indigenous practice of enslavement focus on keeping enslaved families intact and are generally viewed as less physically abusive. This may be true, but the degraded status of slavery is intolerable to those who are enslaved. In 1842, there was a failed slave revolt in Indian Territory, where less than 50 enslaved Africans and enslaved African descendants attempted to flee from the Cherokee to Mexico. In 1866, slavery was ended in Indian Territory by treaty with the U.S.4

In 1889, the Indian Territory was opened by the U.S. government to settlement. People from all over the U.S. and beyond came to settle in Indian Territory. The process further marginalized indigenous people in Indian Territory. This unique blend of Africans, African descendants, indigenous people and a variety of European people from across the United States and abroad created a dynamic and sometimes volatile racial and ethnic mixture. Indian territory did not somehow escape the development of skin color hierarchy, rather the white racial identity was bolstered through violence and segregation. Prior to statehood, nearly a dozen communities experienced incidents of racial violence.5 In each instance, the goal was to punish or run-away Africans or African descendants: Berwyn in 1895, Lawton in 1902 and Boynton in 1904.6 Following the patterns of neighboring states, and prior to statehood, Oklahoma enacted two racial segregation laws covering education.7

Constitution Article 13 | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

In 1907, Oklahoma achieved statehood, and in that same year, a preliminary census showed a population of 1,414,177 -- compromised of 86.8% “white,” 7.9% “Negro,” 5.3% “Indian” and less than 1% “Mongolian.”8 The Oklahoma Constitution identified two races in Article XV, the section for separate schools, the white race and the colored race, defining the term “colored” as all persons of African descent who possess any quantum of negro blood. In addition, Section 11 of Article XXIII of the Oklahoma Constitution similarly discussed only two races, “colored” or “negro” and all others as white. In 1907 and 1908, Oklahoma enacted five additional racial segregation measures covering voting, public education, railroads and miscegenation.9

After statehood, in addition to laws enforcing racial segregation, violence took on a more prominent role. Lynching had taken place in Oklahoma from 1893–1895, with cattle or horse theft and robbery noted as the main offenses.10 After statehood, lynching was reserved primarily for Africans and African descendants.11

The first lynching of a man of African descent happened on December 27, 1907, in Henryetta. Gordon, a man of African descent, was arrested for shooting Bates, a white man, during an argument. When news of the murder made its way to whites, hundreds stormed the jail, took Gordon, lynched him from a telephone pole, and used his body as target practice. Within two days, the whites burned the residential district where the people of African descent resided and established a "sundowner" law.122

From 1908 to 1916, 41 men of African descent were lynched in connection with accusations of murder, complicity in murder, rape and attempted rape as the main offenses alleged by whites.13

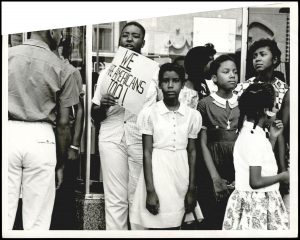

Civil Rights March in Oklahoma City | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

Few Oklahoma cases take up the task of defining race, but those that do are inconsistent and focus on miscegenation, land transfer and one issue of libel related to racial misidentification.14 Oklahoma case law allowed the construction of racial identity based on skin color, community opinion and assumptions. These methods further embed notions of skin color hierarchy, white passing and related familial disruption.

Oklahoma’s history is peppered with cautionary tales of racial terror, race-mixing, racism including sundown town,15 whipping parties,16 lynching and Klan activity.17The most well-known snapshot of Oklahoma history in terms of racial injustice is the Tulsa Massacre. In the Drexel Building, Sarah Page, a white woman, screamed while Dick Rowland, a man of African descent, was riding the elevator she operated.18 It is uncertain what happened; however, the following day, The Tulsa Tribune reported that Rowland had attempted to rape Page.19 The article was titled “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.” That evening hundreds of whites gathered outside the Tulsa County Courthouse, demanding Rowland be turned over to them, but the sheriff refused. On May 31, 1921, whites destroyed more than 1,000 homes and businessesin the district where people of African descent thrived, and an estimated 300 Oklahomans died. Oklahoma’s turbulent racial history, unfortunately, casts a shadow over into our racial present.

“The past is never dead, it’s not even past.”20

Oklahoma’s population is just shy of 4 million people: 74% white, 11.1% Latino,7.8% African American, 9.4% Indigenous, 2.4% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander and 6.3% identify as being of two or more races.21 However, in over 100 years of statehood, racial oppression and inequality are persistent and pervasive. Using these census numbers as a backdrop, racial inequality and disparate impacts, in almost every facet of life and measures of wellbeing, are documented.22

CONCLUSION

We need look no further than the Oklahoma bar to find racialized disparities. The state is 26% nonwhite, and Oklahoma law schools approach or exceed that figure.23 However, among major firms in Oklahoma, there are very few nonwhites at the partnership or director level. The judiciary and law school faculties are equally homogenous. It is ethical and moral to inquire about the impact of such homogeneity in education, policymaking and the administration of the laws. We can no longer afford to make excuses about our inability to achieve diversity in the office, on the bench and at the podium. If we are making efforts, individually and collectively, and those efforts are not working, we must return to the drawing board. Members of the legal profession can accomplish what we set our minds and hearts upon.

I hope Oklahomans associated with the bar and beyond have the will to recognize and change the systems that predetermine negative racial outcomes. The road ahead is long but fruitful. As a legal community and as individuals, we must grieve our hurt feelings, apologize for the hurt we have caused, witnessed and endorsed, listen and learn about the experiences of others, connect with those who want to share their experiences with respect, reengineer methods and systems of reward and punishment, put forth all our power and influence toward our values and repair and heal places of hurt.

Oklahoma’s future does not need to be written by the past. We can recast the future with intention.

Authors’ Note: The authors would like to thank the OCU School of Law and the library staff, particularly Le’Shawn Turner, for support in this project.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Danne Johnson is the Constance Baker Motley Professor of Law at the OCU School of Law and a certified diversity professional. Her awards include the Marian P. Opala Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020 and the Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher Award for Diversity in 2019. She has been recognized twice by the Journal Record as “50 Making a Difference.”

Pamela Juarez is a 2L student at the OCU School of Law, member of the Hispanic Law Student Association and a dedicated research assistant.

- White Supremacy is the belief, attitude, a practice or a policy that establishes or supports the idea that white people constitute a superior race and should therefore dominate society, typically to the exclusion or detriment of other racial and ethnic groups, in particular Black, indigenous or people of color (BIPOC).

- Abramovitch, Seth, Blackface and Hollywood: From Al Jolson to Judy Garland to Dave Chappelle. “In fact, blackface is the oldest American show-business institution. It has its origins in minstrel shows, which began in New York City in the 1830s and quickly gained popularity among white audiences across the country. Performers were usually white men who would ‘black up’ their skin using coal or dark shoe polish. Their mouths were drawn clownishly large, they donned woolly wigs and their performances depicted African-Americans as lazy, hypersexual and superstitious jokers.” www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/blackface-hollywood-al-jolson-judy-garland-dave-chappelle-1185380 (last visited March 10, 2021).

- Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White, Routledge (2008).

- William D. Pennington, Reconstruction Treaties, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=RE001 (last visited March 22, 2021).

- Jimmie Lewis Franklin, African Americans, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=AF003. (last visited March 12, 2021).

- Scott Ellsworth, “Tulsa Race Massacre,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=TU013 (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- Map of Jim Crow America, mchekc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/jim-crow-laws.pdf (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census 1907 Population of Oklahoma, and Indian Territory, www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1907pop_OK-IndianTerritory.pdf (last visited Dec. 17, 2020).

- Map of Jim Crow America, mchekc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/jim-crow-laws.pdf (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- Dianna Everette, Lynching, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entryname=LYNCHING (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- Dianna Everett, Lynching, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=LY00 (last visited March 22, 2021).

- History of Okmulgee County, The Okmulgee Historical Society (1985).

- Dianna Everette, Lynching, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entryname=LYNCHING (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- In Bartelle v. United States, 100 P.45 (Okla. Crim. App. 1909) a woman’s race is decided based on community reputation to invalidate her marriage. If she were determined to be Negro, her marriage would be void and her husband subject to prosecution. Ultimately self-identification seems to carry weight. However, this case and others endorse community reputation and affiliation as admissible evidence of racial identity. Cole et al. v. District Board of School Dist. No. 29, McIntosh County, 123 P 426 (Okla. 1912). Scott et al. v. Epperson et al., 284 P. 19 (Okla. 1930) considers whether Mr. Scott is white under the Oklahoma Constitution. If Scott is determined to be white, his marriage to a Negro woman would be void.

- “Sundown towns” – all-white towns where African Americans were not welcome after the sun went down. These towns had signs posted that read, “All people of color should be out of town before sundown.” Sarah Stewart, Norman Couple Relives History of Sundown Towns in Oklahoma, 2018. News Channel 4 NBC. In the 1940s, Edmond, Oklahoma, promoted itself on postcards with the slogan, “A Good Place to Live … No Negroes.” www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/sundown-towns (last visited Feb. 10, 2021).

- The "whipping party" -- where a large group of whites whipped or beat an African American who was suspected of an offense of some kind. In 1922 alone, according to Oklahoma Gov. Jack Walton, 2,500 whippings took place. Dianna Everette, Lynching, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entryname=LYNCHING (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- Larry O'Dell, Ku Klux Klan, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=KU001 (last visited Feb. 18, 2021).

- Scott Ellsworth, Tulsa Race Massacre, The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=TU013 (last visited Jan. 20, 2021).

- Randy Krehbiel, Tulsa Race Massacre: 1921 Tulsa Newspaper Fueled Racism and One Story is cited for Sparking Greenwood’s Burning, Tulsa World, tulsaworld.com/news/tulsa-race-massacre-1921-tulsa-newspapers-fueled-racism-and-one-story-is-cited-for-sparking/article_420593ee-8090-5cfc-873e-d2dd26d2054e.html (last visited Feb. 18, 2021).

- William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun, Random House (1951).

- QuickFacts, Oklahoma; United States, Census 2020. www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/OK,US/RHI825219 (last visited Feb. 18, 2021).

- Negative racialized outcomes can be seen in the following sectors: Healthcare: All minorities in Oklahoma make up 36% of the population but also have a higher need for medical care. In 2018, non-Hispanic African Americans had the highest age-adjusted cerebrovascular disease death rate (52.5 deaths/100,000 population), followed by Indigenous (42.3) and non-Hispanic whites (39.2); Hispanic individuals had the lowest rate (27.9). In 2018, African American adults had the highest age-adjusted death rates for diabetes (59.0 deaths/100,000 population), followed closely by Indigenous (50.6); Hispanics (25.6) and whites (25.5) were much lower. oklahoma.gov/content/dam/ok/en/health/health2/documents/2019-oklahoma-minority-health-at-a-glance.pdf (last visited Feb. 10, 2021). Children and Poverty: For many minority communities racial and ethnic oppression begin in childhood. African American children in Oklahoma are nearly six times more likely to live in concentrated poverty than white children, and Latino children are more than four times as likely. okpolicy.org/black-and-latino-children-in-oklahoma-are-still-more-likely-to-live-in-concentrated-poverty (last visited Feb. 10, 2021). Incarceration: Despite making up only 7.8% of the Oklahoma population, African Americans are disproportionately affected by incarceration in Oklahoma. One in every 15 adult African American men in Oklahoma is in prison, giving us the highest rate of African American incarceration in the country. Indigenous make up about 9% of Oklahoma’s population, but Native American women make up about 12% of the incarcerated women in the state. Latinos are also overrepresented in Oklahoma prisons, making up 9% of the state population and 15% of its prisoners. okpolicy.org/2019-priority-add-racial-impact-statements-on-criminal-justice-legislation-to-reduce-disparities-in-the-justice-system (last visited Feb. 10, 2021).

- OU College of Law reported 28% of the 1L class as nonwhite in 2019, averaging 23.8% nonwhite since 2011. OCU School of Law recently reported 32% of its 1L class as nonwhite. TU College of Law reported 26% of the 1L class as nonwhite in 2019.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 92 Vol 5 (May 2021)