Oklahoma Bar Journal

Guinn v. U.S.: States' Rights and the 15th Amendment

By Anthony Hendricks

Anthony Hendricks

On Wednesday, Jan. 20, 2021, Joseph Biden was sworn in as the 46th president of the United States of America.1 While several factors have been attributed to his victory, commentators have pointed to the high turnout of Black voters in states that were won in 2016 by former President Trump.2 The number of Black voters who were eligible to vote in the 2020 election was a record high of 30 million,3 and President Biden won 87% of the votes cast by Black voters.4 President Biden acknowledges Black voters’ role in his win in his victory speech, stating, “You’ve always had my back, and I’ll have yours.”5 While many are familiar with the role of the 15th Amendment and the 1965 Voting Rights Act in providing access to the ballot for African Americans, the importance of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1915 decision in Guinn v. United States6 cannot be understated when examining the history of the Black vote. This little talked about appeal out of the state of Oklahoma may be even more relevant now.

While the 2020 presidential election again pointed to the Black vote’s importance in American politics, it also renewed conversations about the fear of voter suppression in the Black community. Oklahoma Senator James Lankford, in an open letter to constituents regarding his decision to request an audit of the 2020 presidential election, acknowledged as much, writing:

What I did not realize was all of the national conversation about states like Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Michigan, was seen as casting doubt on the validity of votes coming out of predominantly Black communities like Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Detroit. After decades of fighting for voting rights, many Black friends in Oklahoma saw this as a direct attack on their right to vote, for their vote to matter, and even a belief that their votes made an election in our country illegitimate.7

Any debate about election security and integrity should come from an understanding of our country’s suffrage movement, including the legacy of Guinn.

OKLAHOMA STATEHOOD AND THE SUPPRESSION OF THE BLACK VOTE

On Nov. 16, 1907, Oklahoma was admitted into the Union as the 46th state. President Roosevelt was reluctant to approve Oklahoma statehood based on fears that the democrat-led state Legislature would enact Jim Crow laws.8Jim Crow takes its name from derogatory slang used to refer to Black men and were sets of laws used to maintain segregation and discriminate against African Americans.9 To combat this, as part of its admission requirement, Oklahoma adopted a state Constitution that allowed men of all races to vote, as required under the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.10 However, President Roosevelt’s fears came true. From 1890 to 1957, Oklahoma passed 18 Jim Crow laws that restricted education, marriage, travel, access to libraries and voting.11

Signing of the first Jim Crow Law | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

Shortly after statehood, the Oklahoma Legislature proposed an amendment to the state Constitution that would require voters to satisfy a literacy test.12 The amendment provided that:

No person shall be registered as an elector of this State or be allowed to vote in any election held herein, unless he be able to read and write any section of the Constitution of the State of Oklahoma; but no person who was, on January 1, 1866, or any time prior thereto, entitled to vote under any form of government, or who at that time resided in some foreign nation, and no lineal descendant of such person, shall be denied the right to register and vote because of his inability to so read and write sections of such Constitution. Precinct election inspectors having in charge the registration of electors shall enforce the provisions of this section at the time of registration, provided registration be required. Should registration be dispensed with, the provisions of this section shall be enforced by the precinct election officers when electors apply for ballots to vote.13

The amendment required potential voters to be able to read and write “any section of the state Constitution as a condition to voting.”14 However, this voting restriction was not applied to all Oklahomans. A voter could be exempt from the literacy requirement if he could prove either that his grandfathers had been voters or had been citizens of some foreign nation before 1866.15

This “grandfather clause” meant that white illiterate men could vote, but Black voters, who were primarily the descendants of slaves, were required to take literacy tests.

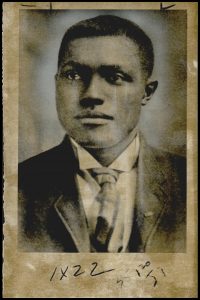

AC Hamlin | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

The impact of this law was felt immediately. A.C. Hamlin, the first African American member of the Oklahoma Legislature, was elected in 1908 before the Oklahoma constitutional amendment was approved.16 He represented a predominately Black community in Logan County. However, after the Oklahoma literacy requirement, Hamilton lost reelection.17This voting restriction and other Jim Crow laws also led to the decline in all-Black towns. Early Oklahoma was home to 50 Black towns and settlements, but many African Americans left Oklahoma in response to the state’s Jim Crow laws.18

CHALLENGES TO OKLAHOMA’S GRANDFATHER CLAUSE

Oklahoma’s grandfather clause was quickly challenged in state court. The Oklahoma Supreme Court in Atwater v. Hassett ultimately held the provision did not violate the 14th or 15th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution or Section 3 of the Enabling Act.19 The court started its analysis by arguing that both the Oklahoma Legislature and Oklahoma electors approved the amendment, and the law was not discriminatory on its face.20 While true, the voting restriction did not explicitly limit African Americans’ rights, the law aimed to exclude Black voters without excluding whites. The law accomplished this without having to say the bad parts out loud.21

The Oklahoma Supreme Court next pointed to the other states that enacted restrictions on voting.22 However, Oklahoma’s amendment was considered “the most sweeping attempt yet made constitutionally to include all whites and exclude all blacks from the privilege of voting.”23 The Oklahoma Supreme Court also took issue with any claim that the constitutional amendment was about discrimination, arguing, “It is a matter of common knowledge that the population of this state is cosmopolitan, embracing people of every creed and race from practically every state in the Union.”24 The Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision in Atwater stood for five years.

GUINN V. U.S. – STATES RIGHTS’ AND THE 15th AMENDMENT

On Nov. 8, 1910, the day of the Oklahoma general election, C. W. Stephenson, Alfred M. Keel, Green Baucom, Sam Fort, Fred McCann, Oliver Andrews, Thomas Pettis and W. T. Smith attempted to vote.25 However, each of these African American voters, and several others, were turned away by election officials Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal.26 All these men were eligible to vote under Oklahoma’s original state Constitution. However, the election officials, relying on the constitutional amendment, turned these voters away and, in some instances, did not allow them even to take the literacy test, even though Guinn and Beal knew several of these voters could have read or written the state Constitution27 Unfortunately, even if Black voters were allowed to take the literacy test, they still may not have been able to vote because the literacy tests that states used were often difficult and, in some instances, described as impossible.28

June 13, 1911, prosecutors indicted Guinn and Beal for conspiracy “to deprive certain negro citizens, on account of their race and color, of a right to vote at a general election held in that state in 1910, they being entitled to vote under the state law, and which right was secured to them by the 15th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.”29 Guinn and Beal were sentenced and then appealed to the 8th Circuit (the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals was not created until 1929) and then the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court considered two questions. First, did Oklahoma’s grandfather clause, which unfairly singled out Black voters, violate the 15th Amendment? Second, if the grandfather clause language was removed, can Oklahoma require literacy tests?30 Guinn and Beal argued states could create requirements and standards for voting, and nowhere in the Oklahoma amendment does it discriminate based on race, color or past servitude.31 Instead, the federal government is alleging the Oklahoma Legislature had a sinister motive to violate the 15th Amendment when it drafted the grandfather clause.32

The solicitor general did not dispute that states had the right to create rules related to voting and did not challenge the literacy test’s validity.33 Instead, the U.S. argued the grandfather clause, because it singles out Black voters, “re-creates and perpetuates the very conditions which the [15th] Amendment was intended to destroy.”34 As a result, the Oklahoma amendment is void.

Chief Justice White, writing the unanimous decision for the court, pointed out what the Oklahoma Supreme Court in Atwater ignored when examining the Oklahoma amendment:

It is true it contains no express words of an exclusion from the standard which it establishes of any person on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, prohibited by the 15th Amendment, but the standard itself inherently brings that result into existence since it is based purely upon a period of time before the enactment of the 15th Amendment, and makes that period the controlling and dominant test of the right of suffrage.35

Because the grandfather clause picked a period before the 15th Amendment existed, the clause had no other purpose but to keep Black people from voting. The Supreme Court struck down the Oklahoma amendment but did find that states could require literacy tests.

THE LEGACY OF GUINN

Victory for African American voters in the Guinn decision was short-lived. In February 1916, a special session of the Oklahoma Legislature passed a new voting restriction that the U.S. Supreme Court would find unconstitutional in Lane v. Wilson.36 But Guinn was still a critical case. It was the first case the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed an amicus brief.37 The NAACP and NAACP Legal Defense Fund played a seminal role in numerous civil rights cases and are still instrumental in challenging new voting laws passed by states in 2021.38

Several states have recently passed or are in the process of passing new voter restriction laws.39 These new laws include additional voter identification requirements, limit voting by mail40 and even punish people who provide voters waiting in lines with water or food.41 These laws are presented as attempts to stop fraud and expand voting rights but are met with the same type of criticism as voting laws in Guinn.42 The cost of Guinn was heavy – disenfranchising Black voters and creating generations of distrust and pain.43 States should remember this cost when drafting new voting laws.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anthony Hendricks is a director at Crowe & Dunlevy in its Oklahoma City office. He is a litigator and legal problem solver who guides clients facing sensitive regulatory, cybersecurity, banking and environmental compliance issues. He is a graduate of Howard University and Harvard Law School.

- Toluse Olorunnipa and Annie Linskey “Joe Biden is sworn in as the 46th president, pleads for unity in inaugural address to a divided nation,” The Washington Post, Jan. 20, 2021, at www.washingtonpost.com/politics/joe-biden-sworn-in/2021/01/20/13465c90-5a7c-11eb-a976-bad6431e03e2_story.html.

- Eugene Scott “Black voters delivered Democrats the presidency. Now they are caught in the middle of its internal battle,” The Washington Post, Nov. 14, 2021, at www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/11/14/black-voters-delivered-democrats-presidency-now-they-are-caught-middle-its-internal-battle.

- Abby Budiman “Key facts about Black eligible voters in 2020 battleground states,” Pew Research, Oct. 21, 2020, at www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/21/key-facts-about-black-eligible-voters-in-2020-battleground-states.

- Teresa Wiltz “2020: The Year Black Voters Said, ‘Hold Up’,” Politico Magazine, Jan. 2, 2021, at www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/01/02/black-americans-power-2020-453345.

- John Eligon and Audra D. S. Burch “Black Voters Helped Deliver Biden a Presidential Victory. Now What?,” The New York Times, Nov. 11, 2020, at www.nytimes.com/2020/11/11/us/joe-biden-black-voters.html.

- 238 U.S. 347 (1915).

- Letter from James Lankford to my North Tulsa Friends, Jan. 14, 2021, bloximages.newyork1.vip.townnews.com/tulsaworld.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/3/f0/3f0cb70a-56c8-11eb-bed6-2b558d2cd9e6/6000e17deb73e.pdf.pdf.

- Frank Keating, “Frank Keating: Honoring A.C. Hamlin would right an embarrassing wrong,” The Oklahoman, July 8, 2020, at oklahoman.com/article/5666249/frank-keating-honoring-ac-hamlin-would-right-an-embarrassing-wrong.

- “A Brief History of Jim Crow Laws” USC Gold School of Law, at onlinellm.usc.edu/a-brief-history-of-jim-crow-laws.

- Dianna Everett, “Enabling Act, 1906,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, at www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=EN001.

- “Jim Crow Laws in Oklahoma,” The Oklahoman, Feb. 13, 2005, at oklahoman.com/article/2884332/jim-crow-laws-in-oklahoma.

- Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347, 355 (1915).

- Id. at 357-358.

- Id.

- Id.

- Michael L. Bruce, “Hamlin, Albert Comstock,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=HA015.

- Id.

- Larry O'Dell, “All-Black Towns,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=AL00.

- 1910 OK 299, 27 Okla. 292, 111 P. 802.

- 1910 OK 299, ¶¶20-21, 27 Okla. 292, 111 P. 802.

- Harry F. Tepker Jr., The Dean Takes His Stand: Julien Monnet’s 1912 Harvard Law Review Article Denouncing Oklahoma’s Discriminatory Grandfather Clause, 62 Oklahoma Law Review 427, 430-431 (2010).

- Atwater v. Hassett 1910 OK 299, ¶¶27-29, 27 Okla. 292, 111 P. 802.

- Harry F. Tepker Jr., The Dean Takes His Stand: Julien Monnet’s 1912 Harvard Law Review Article Denouncing Oklahoma’s Discriminatory Grandfather Clause, 62 Oklahoma Law Review 427, 431 (2010).

- Atwater v. Hassett 1910 OK 299, ¶34, 27 Okla. 292, 111 P. 802.

- Guinn v. United States, 228 F. 103, 104-105 (8th Cir. 1915).

- Id.

- Id. at 109-111.

- Rebecca Onion “Take the Impossible ‘Literacy’ Test Louisiana Gave Black Voters in the 1960s,” Slate, June 28, 2013, at slate.com/human-interest/2013/06/voting-rights-and-the-supreme-court-the-impossible-literacy-test-louisiana-used-to-give-black-voters.html.

- Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347, 353 (1915).

- Id. at 356-357.

- Id. at 358-359.

- Id.

- Id. at 359-360.

- Id. at 360.

- Id. at 364-365.

- 307 U.S. 268 (1939).

- “NAACP Brief History,” Voice of America, July 11, 2012, at www.voanews.com/archive/naacp-brief-history.

- “LDF Issues Statement on Georgia’s Voter Suppression Bill, S.B. 202, Being Signed Into Law” NAACP Legal Defense Fund, March 25, 2021, at naacpldf.org/press-release/ldf-issues-statement-on-georgias-voter-suppression-bill-s-b-202-being-signed-into-law.

- “Voting Laws Roundup: February 2021” Brennan Center for Justice, Feb. 8, 2021, at www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-laws-roundup-february-2021.

- Id.

- Sanya Mansoor “Georgia Has Enacted Sweeping Changes to Its Voting Law. Here's Why Voting Rights Advocates Are Worried,” Time Magazine, March 25, 2021, at time.com/5950231/georgia-voting-rights-new-law.

- Amy Gardner and Amy B. Wang “Georgia governor signs into law sweeping voting bill that curtails the use of drop boxes and imposes new ID requirements for mail voting,” Washington Post, March 25, 2021, at www.washingtonpost.com/politics/georgia-voting-restrictions/2021/03/25/91009e72-8da1-11eb-9423-04079921c915_story.html.

- Russ Bynum, Kate Brumback and Jeff Martin “History, mistrust spurring Black early voters in Georgia,” Associated Press, Oct. 14, 2020, at apnews.com/article/election-2020-virus-outbreak-race-and-ethnicity-voting-health-6fcec151a2c53ff7a39a0a5d90cdc878.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 92 Vol 5 (May 2021)