Oklahoma Bar Journal

Blazing the Trail: Oklahoma Pioneer African American Attorneys

By John G. Browning

John G. Browning

The story of Oklahoma’s earliest African American attorneys is inextricably intertwined with the state’s roots as a multiethnic land of opportunity. Perhaps its first African American lawyer, Sugar T. George, embodied this more than any of his trailblazing counterparts. George (sometimes identified as “George Sugar”) was born into slavery in 1827 in what was then the Muskogee Nation of Georgia. George and his family were among those removed along with their Native American owners in 1828.

When the Civil War broke out, George joined with the “Loyal Creeks” and Seminoles under Opothle Yahola, who fought Confederate forces in Kansas. It is unclear whether George escaped from slavery or purchased his freedom, but it is known from Union Army records that while in Kansas, he enlisted in the First Indian Home Guard. There, his literacy and leadership skills stood out, and George soon achieved the rank of first sergeant.

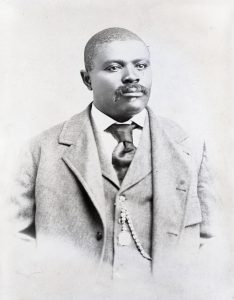

George Napier Perkins | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

After the war, George and his family settled near North Fork Town on the Canadian River, where he soon took on leadership positions in the Creek Nation. In 1868, he represented North Fork Town in the House of Warriors and House of Kings as an elected member of the Muskogee National Tribal Council. Although it is unclear where he received his legal training, Sugar George became both a lawyer and a judge. In addition to assisting other freedmen with legal matters, in 1875 George earned the then-handsome sum of $25 serving as prosecuting attorney for the Arkansas District of the Creek Nation (at the time, all criminal cases involving U.S. citizens in the Indian and Oklahoma territories were under the jurisdiction of federal court, the nearest of which was located at Fort Smith, Arkansas). Later, he served as a judge in the Muskogee District. Buoyed by his prominence in the community and his legal acumen, George accumulated land and, at the time of his death on June 30, 1900, was known as one of the wealthiest men in the territory.

For many African Americans seeking to escape racial violence and restrictions that accompanied the end of Reconstruction in the South, the opening of former Native American lands in the Oklahoma Territory represented more than just a homesteading opportunity. It also represented a chance to create towns where Black people would be free to exercise their political rights without interference. Even prominent leaders of the “Exoduster” movement that led to thousands of African Americans migrating to Kansas, such as Edwin P. McCabe, turned their attention to Oklahoma as the new promised land. As a result, Black settlement in rural Oklahoma was much more extensive than in Kansas. By 1900, African American farmers in the territory owned 1.5 million acres valued at $11 million.1 And while many were freed people or those married to former slaves who acquired allotments in Indian Territory under the Dawes Act, many were African Americans from other states who gained homesteads in the various land runs in Oklahoma between 1889 and 1895. African American migration to the “Twin Territories” (Indian and Oklahoma) produced 32 all-Black towns, including Boley, Taft and Langston City.2 Black farmers, merchants and business owners naturally attracted Black professionals, including doctors, dentists and lawyers.

Some of Oklahoma’s first African American lawyers were among those who had started careers in other states but migrated to Oklahoma for better opportunities. One prime example was George Napier Perkins. Born into slavery in 1842 in Williamson County, Tennessee, Perkins was moved at the age of 15 along with the family that owned him to Little Rock, Arkansas. Perkins had received some education. Although it is unclear how he gained his freedom, Perkins joined the Union Army during the Civil War. He served for three years, ultimately achieving the rank of first sergeant in the 57th Colored Infantry. After marrying Maggie Dillard in 1867, Perkins gained his legal education by attending a night law school.3He was admitted to the Arkansas bar in 1871.4

Perkins thrived in Arkansas. He served as a justice of the peace for Campbell Township for six years, as well as two terms as an alderman on the Little Rock City Council. Perkins was also one of eight African American delegates to the 1874 Arkansas Constitutional Convention, where he witnessed the first of multiple attempts by white Democrats to limit Black citizens’ rights. Those efforts only intensified after the end of Reconstruction. With the passage in 1890 of the Separate Coach Act (which Perkins had publicly opposed) and other Jim Crow legislation, he decided to head west to Oklahoma.

In Oklahoma, as he did in Arkansas, Perkins quickly immersed himself in the practice of law as well as civic life. He became an alternate delegate to the territory’s 1891 Republican convention soon after moving to Guthrie. He served as a justice of the peace in Guthrie and also served eight years on its city council from 1894 - 1902.5However, Perkins found his other political ambitions thwarted. He ran unsuccessfully for police judge in Guthrie in 1896 and quickly found that despite their growing numbers and occasional success in winning offices, African Americans were being largely shut out of territorial politics.

To amplify the voice of the territory’s African Americans, Perkins ventured into the world of journalism. He purchased a Guthrie newspaper, the Oklahoma Guide. Not only was it the Oklahoma Territory’s first African American newspaper, it soon became the longest continuously published Black-owned weekly newspaper in the territory.6Under Perkins’ leadership, the Oklahoma Guide not only served as a platform for encouraging Black migration to Oklahoma, it also staunchly defended African Americans’ civil rights and spoke out against white fears of Black domination.

With African Americans being excluded from early statehood conventions, Perkins and others sought a Black statehood convention to send a delegation to Washington, D.C., in order to lobby for a single statehood bill rather than the twin-state bill being urged. By now, his vocal advocacy for civil rights had earned him the nickname “The African Lion.” He and other Black leaders in both territories formed the Negro Protective League, which was designed to protect the civil rights of the African American community by advocating for a single statehood bill that would ensure these rights in the face of a white Democratic majority pressing Jim Crow legislation. With prominent opponents like 1906 Oklahoma Constitutional Convention president, future governor and avowed racist William H. “Alfalfa Bill” Murray opposing these efforts, Perkins had his work cut out for him. Although President Theodore Roosevelt insisted on the deletion of white supremacist and segregationist provisions from Oklahoma’s proposed constitution before it could be admitted to statehood in 1907, Murray continued pressing for Jim Crow legislation as the first speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives. He said, among other things:

We should adopt a provision prohibiting the mixed marriages of negroes with other races in this State, and provide for separate schools and give the Legislature power to separate them in waiting rooms and on passenger coaches, and all other institutions in the State ... . As a rule they are failures as lawyers, doctors, and in other professions.7

Despite the efforts of George Perkins and other Black leaders, Oklahoma did adopt a variety of Jim Crow laws, including a “grandfather clause” law to deny African Americans’ voting rights. Although he did not act as counsel, Perkins used his unique combination of legal training, newspaper publishing and political leadership to both appeal to whites (including the governor) for repeal of the grandfather clause and to mobilize the African American community to contest it in the courts and fight against disenfranchisement. Although the Oklahoma Supreme Court upheld the grandfather clause8 in 1915, it was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court.9 Unfortunately, George Perkins did not live to see that victory; the “African Lion” died on Oct. 6, 1914.

Completing our triumvirate of early African American legal pioneers in Oklahoma is “the Black Tiger,” William Henry Twine. Twine was born Dec. 10, 1864, in the community of Red House in Madison County, Kentucky. Unlike George Perkins, he was born free, the son of Thomas J. Twine (a wheelwright and runaway slave of mixed African American and Native American ancestry) and Lizzie Twine (a baker described as a “straight born African”).10 Shortly after the Civil War, the family moved to Xenia, Ohio. Young William graduated from Blackburn High School there and then furthered his education at Xenia’s Wilberforce University – the first private historically Black university owned and operated by African Americans. Although Twine briefly pursued a teaching career in Richmond, Indiana, he soon moved to Mexia, Texas, for another teaching position. While in Texas, Twine “read the law” and successfully sought admission to the Texas bar – becoming the “first colored man [who] ever took examination as [a] lawyer in Limestone County” in 1888.11

Twine practiced law in Groesbeck, Texas, for approximately three years. He married Mittie Almira Richardson in 1889, and their marriage would eventually produce six sons. On Sept. 22, 1891, Henry Twine and his growing family were among the 20,000 future Oklahomans who participated in the Sac and Fox Land Run in the Oklahoma Territory. They settled near Chandler on a 160-acre homestead. Twine continued to teach school as a steady source of income but, on Oct. 31, 1891, he was admitted to the Oklahoma Territory Bar. In 1897, he moved to Guthrie and organized the territory’s first African American-owned law firm with two partners, G.W.F. Sawner and E.I. Saddler12 The firm specialized in criminal practice. Twine was the first African American attorney admitted to practice in the United States Courts in Indian Territory.13

In 1897, Twine made history with his defense of George Curley, a man accused of murder, in the U.S. Court for the Northern District of the Indian Territory sitting at Vinita, Oklahoma. Curley was convicted and sentenced to death. On Feb. 11, 1898, Twine filed a petition for writ of error before the U.S. Supreme Court, but the case was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. Twine’s appearance before the Supreme Court was noteworthy because it marked the first appearance by a Black lawyer from Oklahoma or any western state before the nation’s highest court.14

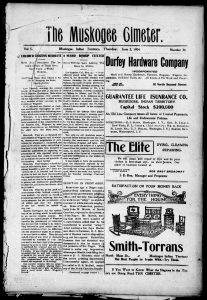

Twine soon moved to Muskogee, in Indian Territory. The work of the Dawes Commission had created a need for lawyers in the territory. There he expanded his work to include not only his law practice but the newspaper business as well. He eventually built a brick office building, housing not only his law practice and his newspaper but other law offices, a doctor’s office, a realtor and a tailor shop. From 1898 to 1904, Twine edited the Pioneer Paper. His second and more successful newspaper, the Muskogee Cimeter, was published from 1904 to 1921. Twine’s family grew as well; of his six sons, three would go on to become lawyers, including Harry Thomas Twine (a 1928 graduate of Harvard University Law School) and Pliny R. Twine (a 1929 Howard Law graduate).15

The Muskogee Cimeter | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

Twine was active in the Republican Party, and his work as a lawyer, newspaper editor/owner and community organizer was critical to the fight for civil rights for the African American community in Oklahoma. He received numerous death threats from racists, including the Ku Klux Klan; in defiance of one such threat, he printed it in his newspaper along with a response that he and his six sons would be ready for a fight.16 Twine’s editorials attacking discriminatory treatment of Blacks in education, transportation and by law enforcement provided a powerful voice for the community. Ridiculing the racist sentiments of “Alfalfa Bill” Murray during the constitutional convention, Twine wrote:

If the Savior of mankind should come to Oklahoma today and go before the constitutional Convention and the color of his cuticle should show the dark tinge of one who had lived in the tropics, the cusses would crucify him anew and Alfalfa Bill would provide the crown of thorns.17

Twine and his editorials also bemoaned the fact that white politicians courted the Black vote when it was needed but ignored African Americans seeking a more prominent role in representing themselves. When no Blacks were selected for the July 1905 Single Statehood Convention in Oklahoma City, Twine and other African American lawyers called for a separate convention, held in Muskogee on April 21, 1905. A second convention was held on Dec. 5, 1906, with 300 Black delegates attending and demanding that the main, all-white Constitutional Convention make no laws restricting African American rights and enfranchisement. When the all-white Constitutional Convention adopted a Constitution laden with Jim Crow provisions, Twine and other African American leaders not only condemned this at a third Black convention in 1907, they traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Roosevelt and urge him to overrule Oklahoma statehood because of the Constitution’s disregard for civil rights. Despite Roosevelt’s sympathizing (and insistence on removal of the offending language from the draft Constitution), after Oklahoma became a state, the very first law passed by the newly minted Oklahoma Legislature was a Jim Crow law establishing segregation on railway cars.

Twine filed a lawsuit challenging this Jim Crow statute soon after it became law. Twine’s civil rights battles were not just waged in courtrooms and in newspaper editorials, where Twine had famously pledged, “We are opposed to Jim Crow no matter where it comes up.”18 Twine was also a key organizer and helped found not only the Negro Protective League of Oklahoma and Indian Territories but also the Oklahoma Anti-Lynching Bureau in 1905.19 He also fought for the acceptance of Black lawyers by the legal profession as a whole. In the early days, a license to practice law did not automatically mean membership in the bar association, and African American lawyers were routinely excluded from bar activities. Twine’s frustration with this is evident in one of his editorials, saying, “The Bar Association reminds us of the Roosevelt club [supporters of Theodore Roosevelt]. They were too busy for any of the colored members of the bar to join at this time.”20 By 1912, with the avid support of Twine and his newspaper, the state’s African American lawyers would form their own group, the Oklahoma Negro Bar Association (largely supplanted by the Southwestern Bar Association by 1941).21

Twine eventually retired from the newspaper business in 1921, but he continued practicing law and advocating for civil rights until his death in Muskogee on Oct. 8, 1933.22 Twine, along with George Perkins and other early Black legal trailblazers, played a critical role in the development of Oklahoma’s African American community and the protection of its civil rights.

As the twin territories and later as a state, Oklahoma provided unheard-of opportunities for African American attorneys – with its “pioneering all-Black communities, the need for legal resolution of countless land disputes, and opportunities to profit in the oil industry development.”23 This unparalleled chance for social and economic mobility led to Oklahoma having more than 60 African American attorneys in 1910 – a figure greater than any other state.24Oklahoma’s early African American lawyers were leaders in the struggle to extend democracy on local and state levels, yet with the pervasive discriminatory effect of Jim Crow laws, racial violence and other factors, pursuing a legal career became both more difficult and less attractive for African Americans. By 1940, the number of Black lawyers had declined so sharply that it wasn’t practical to have a group composed solely of Black Oklahoma-licensed attorneys, leading to what would become the Southwestern Bar Association opening up its membership to African American attorneys in other states. As the ongoing concerns over the lack of diversity in the legal profession reflect, the impact of systemic racism echoes even today.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Browning is a partner in the Plano, Texas, office of Spencer Fane and is a former justice on Texas’ 5th Court of Appeals. He is the author of five law books and numerous articles, including many on African American legal history and has received Texas’ top awards for legal writing, legal ethics and contributions to CLE.

- Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528–1990, at 147 (1998).

- Id. at 148–49.

- Judith Kilpatrick, “(Extra) Ordinary Men: African-American Lawyers and Civil Rights in Arkansas Before 1950,” 53 Ark. L. Rev. 299, 327 (2000).

- Id. at 328–29.

- George Napier Perkins (1842–1914), Encyclopedia of Okla. Hist. & Culture, Okla. Historical Soc’y, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=PE016.

- Nudie Williams, The Black Press in Oklahoma: The Formative Years, 1889–1907, LXI,3 Chronicle of Okla. (Fall 1982).

- Timothy Egan, The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl 271 (2006).

- Atwater v. Hassett, 27 Okl. 292, 111 P. 802 (1910).

- Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347, 360 (1915). The Guinn case is discussed in detail elsewhere in this issue.

- William Henry Twine (1864–1933), Encyclopedia of Okla. Hist. & Culture, Okla. Historical Soc’y, okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=TW006.

- Frank L. Mather, Who’s Who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent 269–70 (1915).

- R.O. Joe Cassity, Jr., “African American Attorneys on the Oklahoma Frontier,” 27 Okla. City U. L. Rev. 245 (Spring 2002).

- Orben J. Casey, And Justice For All: The Legal Profession in Oklahoma, 1821–1989, at 121 Okla. Heritage Ass’n (1989).

- Curley v. United States 171 U.S. 631 (1898) (consolidated with Brown v. United States).

- “Oklahoma Pioneer is Dead,” Pittsburgh Courier, Oct. 21, 1944, at 2.

- William Henry Twine (1864–1933), supra note 10.

- Casey, supra note 13, at 121.

- Arthur L. Tolson, The Negro in Oklahoma Territory, 1889–1907: A Study of Racial Discrimination, 109 (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oklahoma).

- Cassity, supra note 12, at 258.

- The Muskogee Cimeter, Feb. 16, 1905, at 4.

- “Lawyers Organize,” The Muskogee Cimeter, Feb. 24, 1912, at 1.

- Obituary, The Black Dispatch, Oct. 10, 1933, at 1.

- Cassity, supra note 12, at 250.

- Id.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 92 Vol 5 (May 2021)