Oklahoma Bar Journal

The Tulsa Race Massacre: Echoes of 1921 Felt a Century Later

By John G. Browning

John G. Browning

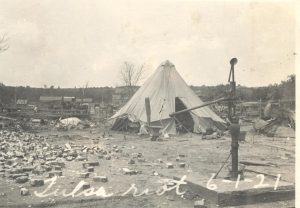

A century ago this month, the thriving African American business district in Tulsa – Greenwood, often referred to as “Black Wall Street” – was home to five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drugstores, eight doctors’ offices, a hospital, 12 churches, law offices, a school, multiple grocery stores and other businesses. But when a young, Black man was arrested and jailed over the questionable accusation of assaulting a young, white woman, it proved to be the spark that ignited one of the ugliest, most devastating episodes of racial violence in American history. In the smoldering embers of what we now refer to as the Tulsa Race Massacre, hundreds of Black citizens lay dead, and as many as 10,000 others were left homeless. Contemporary photos of Greenwood itself resembled Dresden, Germany, after the fire bombings of World War II air raids. More than 35 square city blocks were destroyed. The exact number of dead and the location of many of their remains is still unknown.

But perhaps equally shocking is the fact that for decades afterward, Tulsa itself seems to have buried something else: the truth and scope of what happened. Until recent years, this horrific event seems to have been willfully forgotten, and it was common to encounter whites and Blacks alike who had never heard of or been taught about the Tulsa Race Massacre. As this article shows, discussion of the Tulsa Race Massacre as we mark its centennial – amidst a national discussion of race relations and racial justice – is critical to heeding Santayana’s famed admonition that those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Massacre 1 | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

As two of the preeminent historians to study this event, John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth, have noted:

The story of the Tulsa race riot is a chronicle of hatred and fear, of burning houses and shots fired in anger, of justice denied and dreams deferred. Like the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building some seventy-three years later, there is simply no denying the fact that the riot was a true Oklahoma tragedy, perhaps our greatest.1

But what led up to this tragedy? African Americans, whether they were descended from enslaved persons who had journeyed to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears with Native American tribes like the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Seminole and Chickasaw, or whether they were settlers seeking their fortune in the decades following the Civil War, viewed the “Twin Territories” as a land of equal opportunity. As lawyer Edward McCabe, founder of the all-Black town of Langston put it, the Oklahoma Territory was a place where “the colored man has the same protection as his white brother.”2

Prior to statehood, both “freedmen” and Blacks without Native American ancestry were able to accumulate wealth, both through allotments of land that turned out to be oil rich and sheer hard work and entrepreneurial spirit. The discovery of the massive Glenn Pool oil reservoir led to a boom that transformed Tulsa practically overnight. Tulsa’s white population quadrupled to more than 72,000 between 1910 and 1920, while the Black population swelled from 2,000 to 9,000. And while the oil industry work itself largely excluded African Americans, the wealth changing Tulsa into “The Magic City” spawned economic opportunities for the city’s rapidly growing African American population as well.

The Greenwood District lured such businesspeople as lawyer and real estate agent J.B. Stradford, who built the luxurious three-story, 68-room Stradford Hotel; John and Loula Williams, who owned several businesses, including the Dreamland Theater; grocer and real estate developer O.W. Gurley; B.C. Franklin, a lawyer whose expertise would prove critical in the aftermath of the massacre; and newspaperman A.J. Smitherman, owner of the Tulsa Star. Greenwood had its own hospital, numerous churches and an array of salons, shops and restaurants, serving over 11,000 people. While white Tulsans derisively referred to Greenwood as “Little Africa” (or worse), the district had earned its national moniker: “Black Wall Street.”

As Tulsa-based historian Hannibal B. Johnson, author of Black Wall Street and other books about Greenwood, points out:

Greenwood was perceived as a place to escape oppression – economic, social, political oppression – in the Deep South. It was an economy born of necessity. It wouldn’t have existed had it not been for Jim Crow segregation and the inability of Black folks to participate to a substantial degree in the larger white-dominated economy.3

However, the dream of Black success and wealth-building was regularly interrupted by racial conflict. Black veterans who had served overseas in World War I and experienced life outside of Jim Crow restrictions came home to a society that viewed them as inferiors. During the “Red Summer” of 1919, race riots erupted in more than 30 cities across the United States. In Tulsa, J.B. Stradford found his wealth didn’t prevent him from being forced to sit in a “Jim Crow” car as a paying passenger on the Midland Valley Railroad; he took his case to the Oklahoma Supreme Court and lost.4 And with plummeting oil prices in 1921, once-prosperous whites simmered with resentment at the success of Greenwood’s business community.

By May 30, 1921, what had been simmering boiled over with the accusation that 19-year-old Black resident Dick Rowland had assaulted 17-year-old Sarah Page, a white elevator operator at the Drexel Building at 319 S. Main St. Rowland, a shoeshiner, apparently stumbled while entering or exiting the elevator, causing him to inadvertently grab Page’s arm. The young woman screamed, causing a clerk at Renberg’s (a clothing store on the first floor of the Drexel Building) to rush to investigate. That clerk summoned the police, jumping to the conclusion that Rowland had attempted to assault Page. No record exists of what Sarah Page actually told the police when interviewed, but whatever was said doesn’t seem to have spurred the police into anything but “a rather low-key investigation into the affair.”5

The next morning, May 31, 1921, Rowland was arrested by two Tulsa police officers – Detective Henry Carmichael, who was white, and Patrolman Henry Pack, one of the few African Americans on Tulsa’s 75-man police force. Rowland was booked at police headquarters before being placed in the jail at the Tulsa County Courthouse’s top floor. By the afternoon, word had spread to Tulsa’s main newspaper, the Tulsa Tribune, and the result was a front-page story titled “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.”6 An inflammatory editorial, purportedly titled “To Lynch Negro Tonight,” also ran in this edition, further fanning the flames of mob sentiment.7

Dreading the potential for violence, Black community leaders met at A.J. Smitherman’s newspaper office to discuss a response. Some recommended patience based on Sheriff Willard McCullough’s promise to protect Rowland. But a white mob had already gathered outside the courthouse where Rowland was being held. Fearing the worst, a group of at least 25 African American armed residents – many of them World War I veterans carrying their military small arms – marched to the courthouse to aid in protecting Rowland. More Black residents of Greenwood arrived later. As the crowd swelled and the tension mounted, a scuffle broke out when a member of the white mob grabbed the weapon of a Black veteran. A shot rang out, and chaos ensued. Greenwood residents tried to fight back, but they were battling not only superior numbers but advanced weaponry as well. The white mob employed machine guns to deadly effect, along with biplanes (possibly belonging to a local oil company) that dropped incendiary turpentine bombs that set the Greenwood district ablaze.

B.C. Franklin would later vividly recall the aerial assault:

I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted, and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top.8

As many as 10,000 people were in the white mob that stormed the Greenwood district, including not only armed white men but women, children and members of the National Guard, police department and sheriff’s department. A white Tulsa resident, Ruth Sigler Avery, would later recount some of the grisly sights she witnessed as a girl, including the “cattle trucks heavily laden with bloody, dead, black bodies. They looked like they had been thrown upon the truck beds haphazardly for arms and legs were sticking out through the slats.”9

Massacre 2 | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

By daybreak on June 1, 1921, the catastrophic toll was evident. As many as 300 people were dead, at least 800 more wounded and most of the community’s 10,000 residents were rendered homeless. More than 1,100 homes were burned (another 314 were looted but not burned), along with five hotels, 31 restaurants, a school, eight doctor’s offices, Greenwood’s only hospital, two theaters, a dozen churches and dozens of other businesses – in all, 35 square blocks were destroyed. In today’s dollars, estimates of the property losses range from $20 million to more than $200 million.10

In the aftermath, many Black residents were detained in makeshift internment camps. Even after order was restored, it was official policy to release a Black detainee only upon the application of a white person. Some leading white citizens expressed remorse, like Bishop Mouzon:

Civilization broke down in Tulsa. I do not attempt to place the blame, the mob spirit broke and hell was let loose. Then things happened that were on a footing with what the Germans did in Belgium, what the Turks did in Armenia, what the Bolsevists [sic] did in Russia.11

Despite such sentiments, the title of the clergyman’s sermon reveals what he and Tulsa’s white establishment were identifying as the cause of the massacre: “Black Agitators Blamed for Riot.”12 Mayor T.D. Evans’ sentiments were typical, saying, “Let the blame for this Negro uprising lie right where it belongs – on those armed Negroes and their followers who started this trouble … ”13 Indeed, the grand jury that was convened (and which issued its report on June 25, 1921) echoed the one-sided, laughably incredible white Tulsa interpretation of the massacre, pointing to “agitation among the Negroes for social equality” as the chief cause.14 No white person was ever arrested or brought to justice for crimes during the massacre; instead, Black residents (including J.B. Stradford, who relocated to Chicago) were charged with inciting a riot. None were prosecuted. Incredibly, the indictments of A.J. Smitherman and 55 others charged with inciting the riot remained on the books until a University of Buffalo historian, Barbara Seals Nevergold, pressed Tulsa County District Attorney Tim Harris to dismiss the baseless charges, something he did in a 2007 ceremonial hearing.15

Adding to the tragedy, city officials sought to prevent Greenwood residents and business owners from rebuilding by passing a fire zoning ordinance just six days after the massacre that specified expensive new building materials and standards, which would make it cost prohibitive to rebuild. Practicing out of a tent, B.C. Franklin and other Black lawyers fought to strike down the oppressive ordinance. They sought injunctive relief and won. Later, the Oklahoma Supreme Court held that the ordinance “constituted an invalid taking of property without due process of law.”16

Massacre 3 | Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society

Ironically, some of the most complete documentation of the Tulsa Race Massacre is available thanks to an otherwise obscure Oklahoma Supreme Court case arising out of an insurance coverage dispute.17 William Redfearn was a white man who owned two buildings in Greenwood, the Dixie Theatre and the Red Wing Hotel, both of which were destroyed in the massacre. They were insured for a total of $19,000, but American Central Insurance Co. refused to pay based on a riot exclusion clause in the policies. Redfearn sued, lost at trial and appealed all the way to the Oklahoma Supreme Court. Although Redfearn lost, the briefing and record of the case – which includes hundreds of pages of eyewitness testimony and other documentation – provides valuable insight into the massacre, especially the culpability of the Tulsa police department and their “special deputies” who joined in the destruction and violence.18

The Redfearn case is noteworthy for the information it provides in part because of the active campaign Tulsa’s leaders embarked upon in the wake of the massacre to erase the event from the historical record. Police and fire department records mysteriously disappeared, inflammatory newspaper articles were cut out and victims were buried in unmarked graves.19 As one historian of the massacre, Scott Ellsworth, observed, “What happens fairly rapidly is this culture of silence descends, and the story of the riot becomes actively suppressed.”20

JUSTICE DENIED OR DELAYED?

According to the 2001 Commission Report, Tulsa residents filed $1.8 million in riot-related claims against the city between June 14, 1921, and June 6, 1922. Virtually all were disallowed, with one notable exception: A white resident obtained compensation for guns taken from his shop.21 Of the lawsuits that were filed, none went anywhere, and in 1937, Judge Bradford J. Williams summarily dismissed most of those that were still languishing on the dockets. While some business owners persevered and managed to reopen venues like the Dreamland Theater, many simply could not.22 The “urban renewal” that brought Interstate 244 to Tulsa, splitting the north side from the south side, did not help Greenwood. In Tulsa today, where African American residents experience higher rates of unemployment and lower life expectancies, Mayor G.T. Bynum has acknowledged “the racial and economic disparities that still exist today can be traced to the 1921 race massacre.”23

In 1997, an 11-member “Tulsa Race Riot Commission” was formed and charged with developing a historical record of the massacre. In 2001, the commission issued its report, recommending, among other things, that the state Legislature, governor and Tulsa’s mayor and city council make payment of reparations to survivors and their descendants. Shortly after this report was released, Oklahoma lawmakers passed the “1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act.”24> While it adopted many of the findings of the commission, the legislation did not provide financial compensation to survivors of the massacre or their descendants. And in fall 2001, then-Governor Frank Keating dismissed the notion of any state culpability in the massacre, insisting that paying reparations would be prohibited under Oklahoma law.25

In 2003, a legal team that included Johnnie Cochran Jr. and Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree sued the state of Oklahoma, the city of Tulsa and the Tulsa police department on behalf of more than 200 survivors and their descendants, seeking “restitution and repair.” But in March 2004, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma – noting that it took “no comfort or satisfaction in the result” – dismissed the case on limitations grounds.26 Similarly taking “no great comfort,” the 10th Circuit affirmed that dismissal later that year.27 The following year, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case.28 Despite such setbacks and inspired by Oklahoma’s success in suing opioid manufacturers under a “public nuisance” theory of recovery in 2019, the last living massacre survivors and descendants filed a lawsuit in 2020 against the city of Tulsa and several other defendants. That lawsuit is still pending.

CONCLUSION

The memories of the shameful legacy of the Tulsa Race Massacre are not just being kept alive in the courtroom, however. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, an organization working with the city and other civic partners, has planned a 10-day commemoration starting on May 26, 2021. At the intersection of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street, a state-of-the-art history center called “Greenwood Rising” will be dedicated on June 2, 2021.29 On an exterior wall of the center will be a fitting quote from writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin that should answer any lingering question of why it is so important to remember this dark episode in Oklahoma history: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Browning is a partner in the Plano, Texas, office of Spencer Fane and is a former justice on Texas’ 5th Court of Appeals. He is the author of five law books and numerous articles, including many on African American legal history and has received Texas’ top awards for legal writing, legal ethics and contributions to CLE.

- John Hope Franklin & Scott Ellsworth, History Knows No Fences: An Overview, in Tulsa Race Riot: A Report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, at 32 (Feb. 28, 2001) [hereinafter Tulsa Race Riot Report].

- Victor Luckerson, The Promise of Oklahoma, Smithsonian (Apr. 2021), www.smithsonianmag.com/history/unrealized-promise-oklahoma-180977174.

- Antoine Gara, The Bezos of Black Wall Street, Forbes (June 18, 2020), www.forbes.com/sites/antoinegara/2020/06/18/the-bezos-of-black-wall-street-tulsa-race-riots-1921/?sh=62519b40f321; see also Hannibal B. Johnson, Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District (Sept. 1, 1998).

- Stratford v. Midland Valley R.R. Co., 128 P. 98, 99, 36 Okla. 127 (Okla. 1921). The case style misspells his name, though Stradford’s father had been emancipated in Stratford, Ontario.

- Scott Ellsworth, The Tulsa Race Riot, in Tulsa Race Riot Report, supra note 1.

- We only know this thanks to a graduate student in history named Loren Gill, who did his 1946 master’s thesis at TU on the massacre. Gill found an extant copy of the article, despite the fact the original bound volumes of the now-defunct newspaper had the May 31 front page and editorial page deliberately torn out (a microfilm copy of the paper exists, but the pages in question were removed before the microfilming was done).

- Like the front page, the editorial page was torn from the surviving paper, and therefore, its exact content is subject to conjecture. However, multiple witnesses recalled the editorial discussing a potential lynching. See Franklin & Ellsworth, supra note 1, at 59.

- The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims, Manuscript of B.C. Franklin (original in National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.), excerpted in Allison Keyes, A Long-Lost Manuscript Contains a Searing Eyewitness Account of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, Smithsonianmag.com (May 27, 2016).

- Ruth Avery, Fear: The Fifth Horseman, Oral History (quoted in Tulsa Race Riot Report, supra note 1).

- Clark Merrefield, The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and the Financial Fallout, Harv. Gazette (June 18, 2020), news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/06/the-1921-tulsa-race-massacre-and-its-enduring-financial-fallout/ (citing Chris Messer, Thomas Shriver & Alison Adams, The Destruction of Black Wall Street: Tulsa’s 1921 Riot and the Eradication of Accumulated Wealth, AM. J. Economics & Sociology (Oct. 2018)).

- “Black Agitators Blamed for Riot,” Tulsa World, June 6, 1921, at 1.

- Id.

- “Public Welfare Board Vacated by Commission,” Tulsa Trib., June 14, 1921, at 2.

- “Grand Jury Blames Negroes for Inciting Race Rioting,” Tulsa World, June 26, 1921, at 1.

- Jay Rey, “Justice Delayed But, at Last, Not Denied Thanks to a UB Historian, Vindication For a Newsman Indicted in Tulsa Race Riot,” Buffalo News (Dec. 11, 2007), buffalonews.com/news/justice-delayed-but-at-last-not-denied-thanks-to-a-ub-historian-vindication-for-a/article_4b7f0d85-4c84-5d59-84cc-60f51d4beaba.html.

- Scott Ellsworth, Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (Jan. 1, 1992). The idea of takings claims as a means of redress for race riots has been advanced by at least one scholar. See Melissa Fussell, “Dead Men Bring No Claims: How Takings Claims Can Provide Redress for Real Property Owning Victims of Jim Crow Race Riots,” 57 WM. & Mary L. Rev. 1913 (2016).

- Redfearn v. Am. Central Ins. Co., 243 P. 929 (Okla. 1926).

- For an excellent account of this case and its value as a lens into the massacre’s origin and progress, see Alfred Brophy, “The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 in the Oklahoma Supreme Court,” 54 Okla. L. Rev. 67 (2001).

- Brakkton Booker, Scientists Discover Unmarked Coffins During Search for 1921 Tulsa Massacre Victims, NPR.org (Oct. 23, 2020), www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/10/23/927265545/scientists-discover-unmarked-coffins-during-search-for-1921-tulsa-massacre-victi#:~:text=Researchers%20in%20Tulsa%2C%20Okla.%2C,the%20city%2Downed%20Oaklawn%20Cemetery.

- Maggie Astor, “What to Know About the Tulsa Greenwood Massacre,” N.Y. Times (June 20, 2020), www.nytimes.com/2020/06/20/us/tulsa-greenwood-massacre.html.

- Larry O’Dell, Riot Property Loss, in Tulsa Race Riot Report, supra note 1.

- Id.

- Bloomberg Philanthropies Announces City of Tulsa Will Receive $1 Million for Public Art Project Honoring America’s First “Black Wall Street,” Bloomberg Philanthropies (Jan. 15, 2019), www.bloomberg.org/press/bloomberg-philanthropies-announces-city-tulsa-will-receive-1-million-public-art-project-honoring-americas-first-black-wall-street.

- 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act of 2001, Okla. Sess. L. Serv. Ch. 315 (West) (codified at Okla. Stat. Ann. Tit. 74, 8000.1(3) (2002)).

- Adrian Brune, Tulsa’s Shame, THE NATION (Feb. 28, 2002), www.thenation.com/article/archive/tulsas-shame.

- Alexander v. Oklahoma, U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5131, at 3 (N.D. Okla. March 19, 2004).

- Alexander v. Oklahoma, 382 F.3d 1206, 1220 (10th Cir. 2004).

- Alexander v. Oklahoma, 544 U.S. 1044 (2005), cert. denied; Chris Casteel & Jay Marks, “Race-Riot Recourse Blocked, Supreme Court Refuses Appeal After Decision,” The Oklahoman (May 17, 2005), www.oklahoman.com/article/2896719/race-riot-recourse-blocked-br-supreme-court-refuses-appeal-after-decisions.

- Tim Madigan, “Remembering Tulsa: American Terror,” Smithsonian (April 2021), www.smithsonianmag.com/history/tulsa-race-massacre-century-later-180977145.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 92 Vol 5 (May 2021)