Oklahoma Bar Journal

Water Unity in Oklahoma: A History of the 2016 Water Settlement Agreement

By Christine Pappas

Isha10/Wirestock Creators | #503144911 | stock.adobe.com

“While we have been sovereign since time immemorial, sovereignty is something we should never take for granted. As tribal leaders we have a duty to engage in this process and exercise our rights as sovereign nations to protect the interests of our people.” – Gov. Bill Anoatubby, Chickasaw Nation[1]

The story of the 2016 Water Settlement Agreement begins with the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek of 1830. The Choctaw Nation agreed to trade their homelands in Mississippi for land west of the Mississippi River that would be held in fee simple and exclusive of any state government.[2] Choctaw scouts surveyed available lands and chose what is now water-rich southeast Oklahoma. The Chickasaw Nation joined their cousin tribe in 1837 and became a retroactive party to the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.[3] The Chickasaw Nation signed a new treaty with the U.S. federal government in 1855. After the Civil War, both the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations signed the Treaty of 1866, which ceded lands west of the 98th meridian to the U.S. government.[4] This treaty also allowed railroads to cross tribal land, enabling increased nontribal settlement.[5]

The Choctaw and Chickasaw nations thrived in their new lands, establishing schools, infrastructure, a legal code and communities.[6] They lived near ample water and constructed ferries and toll bridges over the Red, Blue and Kiamichi rivers. Most tribes in Oklahoma began to lose land base under the 1887 Dawes Act, but it did not apply to the Five Tribes. In 1897, however, the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations agreed to accept the allotment policy and abolish communal ownership of land.[7] In 1907, Oklahoma became a state, but as McGirt v. Oklahoma demonstrated, Congress failed to disestablish tribal reservations.[8] Water rights based on treaty obligations were unaffected by statehood.

Tribal governments’ influence was reduced under assimilation and termination policies, but federal policies that strengthened tribal self-determination were passed starting in the 1960s.[9] As tribes were growing in power, Oklahoma was engaging in an ambitious agenda of dam and reservoir building. Most of Oklahoma’s 200 lakes were constructed by damming a creek or river and inundating the surrounding area.[10] Many tribal towns, cultural sites and burial grounds were flooded. Tribes were nominally consulted during this process. The state of Oklahoma contracted with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on April 9, 1974, to construct the dam on the Kiamichi River to create Sardis Lake for flood control purposes.[11]

In the 1980s, the state of Texas unsuccessfully investigated purchasing water rights from Oklahoma and acknowledged the rights the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations had on water based on the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.[12]

In 1998, the state of Oklahoma refused to pay for the construction of Sardis Lake because it would not control the water in the lake. They were sued by the Army Corps of Engineers. In 2009, Oklahoma was ordered to pay its debt. Seeing an opportunity to secure needed water rights, the city of Oklahoma City agreed to assume the state of Oklahoma’s debt and pay for the construction of Sardis Lake if it could be granted a permit for the totality of water in Sardis Lake. Oklahoma City applied to the Oklahoma Water Resources Board (OWRB) for such a permit, and it was granted in 2010.[13]

Although the treaty rights to water under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek had not been defined, the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations knew it was not zero.[14] Susan Work notes, “Tribes in Oklahoma, at a minimum, possess reserved water rights.”[15] In 2011, these tribes filed suit in federal court against the state of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City and the Oklahoma City Water Utilities Trust, asserting treaty rights to the water. In 2012, the suit was stayed to allow for settlement negotiations.[16]

Intensive negotiations continued until the settlement agreement was reached by the parties on Aug. 17, 2016.[17] The terms of the agreement were passed by the U.S. Congress in the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act in 2016.[18]

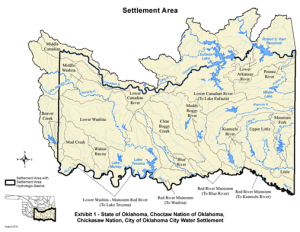

Settlement area map. Courtesy Water Unity Oklahoma, www.waterunityok.com.

Starting in 2016, the parties worked vigorously to meet the preconditions of the agreement as outlined in Section 4 of the settlement agreement. To prepare for the technical demands of the agreement, the Chickasaw Nation invested in its Natural Resources Office, and the Choctaw Nation invested in its Office of Water Resource Management.[19] The Oka’ Institute was created at East Central University as a clearinghouse for water policy, and it assisted with providing scientific information.[20] East Central University created a Master of Science degree in water resource policy and management that has graduated 60 students, many of whom work on issues relating to the settlement agreement.[21] Additionally, documentation of the Kiamichi Basin Hydrologic Model was filed at the OWRB’s Oklahoma City offices, and the Atoka and Sardis Conservation Projects Fund was created. The cases Chickasaw Nation and Choctaw Nation v. Fallin et al. and OWRB v. United States et al. were dismissed.[22]

In 2017, Oklahoma City applied for a water permit pursuant to the settlement agreement to divert stream water from the Kiamichi River. Despite 85 protests filed during the hearing, the OWRB granted the permit. A petition for judicial review – Leo v. OWRB – was filed in the District Court of Pushmataha County on Nov. 8, 2017. The local residents believed the settlement agreement did not protect the Kiamichi Basin adequately and filed suit against the OWRB but did not include Oklahoma City in the suit.[23]

The case effectively delayed the implementation of the settlement agreement for over five years, but the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision in Leo v. OWRB hinges on procedure and not water law. The Oklahoma Supreme Court held that the OWRB clearly has the authority to appropriate water, and the district courts have the authority to adjudicate water rights.[24]

The city of Oklahoma City was not named as a respondent and entered a special entry of appearance in the case. The district court denied the city’s and the OWRB’s motions to dismiss on May 7, 2018, concluding that no prejudice was suffered by either entity by not listing the city as a party. On June 1, 2020, the district court affirmed the OWRB’s order granting the city’s stream water permit. Petitioners appealed. The city filed a cross-appeal of the May 7, 2018, order denying the motion to dismiss.[25]

Before taking final action on a stream water permit application, the OWRB must determine from the evidence presented, pursuant to O.A.C. §785:20-405(a), whether:

(1) Unappropriated water is available in the amount applied for;

(2) The applicant has a present or future need for the water and the use to which applicant intends to put the water is a beneficial use;

(3) The proposed use does not interfere with domestic or existing appropriative uses;

(4) If the application is for the transportation of water for use outside the stream system wherein the water originates, the provisions of Section 785:20-5-6 are met.[26]

When these four conditions are met, the OWRB shall approve the permit.[27] Taking each point in turn, the Oklahoma Supreme Court confirmed the OWRB’s order. Notably, point two requires consideration of “beneficial use” before a permit can be issued. Petitioners alleged that “environmental issues” should be considered such that a nonconsumptive instream flow requirement might be established.[28] However, the court concluded, “General protection of environmental flows is not one of the statutory elements to be determined by the Board.”[29]

The Oklahoma Supreme Court decided Leo v. OWRB on Oct. 2, 2023, removing the final barrier to Oklahoma City’s application for a water permit. After all the preconditions were met, publication of certification by the U.S. Department of the Interior was published in the Federal Register on Feb. 28, 2024, making the settlement act effective.[30]

The settlement agreement is unique in the state of Oklahoma for several reasons. It brings state, city and tribal entities to the negotiating table to create an agreement that will mutually benefit rural and urban water interests in Oklahoma. The settlement agreement calls on Oklahoma City to engage in conservation measures before it may utilize water from Sardis Lake or the Kiamichi River. Additionally, the amount of water that can be taken by Oklahoma City will be based on the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation’s lake level management plan so that environmental and recreational needs in southeast Oklahoma are not diminished. The settlement agreement may be the one area of water law in Oklahoma that legally protects the sustainability of water resources.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Christine Pappas is chair of the Department of Politics, Law and Society at East Central University in Ada, home of Oklahoma’s only four-year Bachelor of Science degree in legal studies. She is also the policy and education coordinator for the Oka’ Institute as well as the director of ECU’s Master of Science in water resource policy and management. She has been a member of the OBA since 2010.

ENDNOTES

[1] Statement of Gov. Bill Anoatubby quoted in “Tribal Sovereignty at Forefront; Water Settlement Secures Tribes’ Historic Standing,” Tony Choate, Chickasaw Times, Dated: September 2016, updated 2024.

[2] “Next Steps for the Water Settlement,” comments by Stephen Greetham, East Central University, Nov. 8, 2023.

[3] Oka Holisso: Chickasaw & Choctaw Water Resource Planning Guide, Chickasaw Press: Ada, 2022.

[4] “Tribal Water Rights: The Necessity of Government-to-Government Cooperation,” Susan Work, OBJ Vol. 81, No. 5, pp. 375-379, 2010.

[5] “Modern Sequoyah: Native American Political Power in Oklahoma Politics,” Christine Pappas and Jacintha Webster in Hardt, Jan C. et al. ed. Oklahoma Government and Politics, Kendall Hunt: Dubuque, Iowa: pp. 43-62, 2024.

[6] Id.

[7] Oka Holisso, supra note 3.

[8] McGirt v. Oklahoma, 591 U.S. ___ 2020.

[9] “Modern Sequoyah,” supra note 5.

[10] “Lakes and Reservoirs.” Oklahoma Historical Society, https://bit.ly/4boTlb9.

[11] Water Settlement, www.waterunityok.com.

[12] Greetham, supra note 2.

[13] OWRB v. Leo, 2023 OK 96.

[14] Greetham, supra note 2.

[15] “Tribal Water Rights: The Necessity of Government-to-Government Cooperation,” Susan Work, OBJ Vol. 81, No. 5, pp. 375-379, 2010, at 379.

[16] OWRB v. Leo, 2023 OK 96.

[17] Greetham, supra note 2.

[18] Public Law 114-322.

[19] “Tribal Sovereignty at Forefront; Water Settlement Secures Tribes’ Historic Standing,” Tony Choate, Chickasaw Times, Dated: September 2016, updated 2024.

[20] Oka’ The Water Institute at East Central University, www.okainstitute.org.

[21] “ECU Water Master’s Program Graduates 50th Student,” https://bit.ly/4bknsk7.

[22] Federal Register, Vol. 89, No. 40. Feb. 28, 2024, p. 14700.

[23] OWRB v. Leo, 2023 OK 96.

[24] 82 O.S., §105.1.

[25] OWRB v. Leo, 2023 OK 96.

[26] Id.

[27] 82 O.S. §105.12(A)(5).

[28] OWRB v. Leo, 2023 OK 96.

[29] Id.

[30] Federal Register, Vol. 89, No. 40. Feb. 28, 2024, p. 14700.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 95 No. 6 (June 2024)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.