Oklahoma Bar Journal

The Stigler Act Amendments of 2018

By Conor Cleary

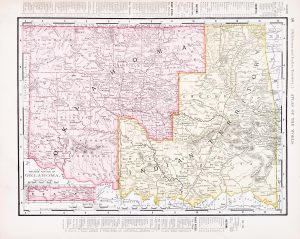

#28845706 | adobestock.com

On Dec. 31, 2018, President Trump signed into law the Stigler Act Amendments of 2018.1 The amendments are the first comprehensive overhaul of the law governing conveyances of restricted Indian land in the state of Oklahoma in nearly 75 years and represent a significant change in federal Indian policy with respect to the Five Tribes of Oklahoma –

the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole nations. This article summarizes the legal history of restrictions on alienation of the allotted and inherited lands of the Five Tribes, principally explaining how the amendments eliminated any minimum Indian blood quantum necessary to inherit or acquire restricted land, substituting instead a requirement that the owner be a “lineal descendant” of an original Indian allottee on the Dawes Rolls.

After their forced removal to Indian Territory, the Five Tribes owned their respective lands communally. Tribal members had the right to occupy and make use of a portion of the communal estate but did not individually own it. In the latter half of the 19th century, federal Indian policy shifted to one of assimilation, accomplished through the policy of allotment whereby tribal land holdings were dissolved and allotted to individual tribal members. In 1898, Congress enacted the Curtis Act requiring the Five Tribes to allot their lands in severalty.2 Pursuant to agreements negotiated with the federal government, each tribal member, known as the “allottee,” received a homestead allotment and a surplus allotment, with the acreages of each varying by tribe.3

Accompanying each allotment was a restriction on the ability to alienate it without approval from the federal government.4 The restrictions protected the Indian landowners from making improvident decisions to sell their lands on unfair terms to often unscrupulous purchasers. Conveyances made in violation of the restrictions were void. Although the restrictions initially applied to all allottees,5 they soon depended on the Indian blood quantum of the allottee, which became a crude heuristic for determining the capacity to convey land free of governmental supervision. A 1908 law, for example, removed restrictions on all of the allotted lands –

both homestead and surplus – of those allottees who were less than one-half blood.6 Conversely, those allottees who were three-fourths or more retained restrictions on both their homestead and surplus lands.7 Those allottees possessing at least one-half but less than three-fourths Indian blood could freely alienate their surplus lands, but their homestead allotments remained restricted.8

The first restrictions applied only to the allottees and their allotted lands. In order to convey their allotted lands, restricted allottees had to obtain permission from the secretary of the interior.9 Initially, the restrictions did not apply to the heirs of the allottee, and once the allottee died, the heir could alienate the inherited land free of any restrictions.10 Subsequently, however, Congress began applying restrictions to the heirs of allottees as well. The 1908 law, for example, provided full-blood heirs would continue to be restricted.11 Importantly, this law shifted the authority to approve conveyances by restricted heirs from the secretary of the interior to the Oklahoma state courts,12 a policy that remains in effect to this day.13

In 1947, Congress passed the Stigler Act, a comprehensive overhaul of the law governing conveyances by heirs of allottees.14 It tightened restrictions, requiring any heir of at least one-half Indian blood to obtain approval of a conveyance of inherited land in Oklahoma state court.15 It also sets forth a detailed procedure for how to obtain approval in the Oklahoma state courts. Among other things, it requires the filing of a petition requesting approval of the conveyance and notice of the proceeding to attorneys of the Department of the Interior who represent the restricted landowner. The federal attorney obtains an appraisal to verify that the amount offered for the conveyance is adequate and fair. A hearing is set to approve the conveyance, notice of which is published in a newspaper in the county so other prospective purchasers can appear and competitively bid for the land.16

Although the Stigler Act broadened the application of the restrictions on heirs to anyone of at least one-half Indian blood, the inevitable result of the law was land lost its restricted status any time it was inherited or acquired by an heir less than one-half blood. The results speak for themselves. Of the approximately 16 million acres of the lands of the Five Tribes allotted to individual tribal members,17 today only a little more than 2% remains restricted.18

The ongoing loss of restricted land caused by its inheritance by an heir of less than one-half Indian blood prompted calls for reform. On Dec. 31, 2018, President Trump signed into law the Stigler Act Amendments of 2018.19 The “single objective” of the Stigler Act Amendments is “to eliminate the blood quantum requirement” to own land in restricted status.20 Rather than tying restrictions to blood quantum, the amendments provide that restricted land may be acquired21 by any “lineal descendant by blood of an original enrollee whose name appears on the Final Indian Rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory ... of whatever degree of Indian blood.”22 Accordingly, restricted property inherited by heirs who are lineal descendants by blood of an original enrollee whose name appears on the final Indian rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory will remain restricted regardless of the heirs’ blood quanta.23 Similarly, restricted property conveyed to another person who is also a lineal descendant by blood of an original enrollee on the final Indian rolls will remain restricted regardless of the grantee’s blood quantum.

Although the Stigler Act Amendments broaden the scope of persons eligible to inherit or acquire restricted property, they do not change the approval process for conveying restricted land. The procedure provided in the Stigler Act summarized above continues to govern all conveyances of restricted land, and conveyances of restricted land made in derogation of this procedure are void.24 The Stigler Act Amendments are prospective in application and do not retroactively impose restrictions on land that previously lost its restricted status by virtue of being inherited or acquired by someone less than one-half blood.25 Similarly, oil and gas leases obtained from Indian landowners of less than one-half blood without state court approval before the enactment of the amendments remain valid for the leases’ duration.26

Because many more people are now eligible to inherit or acquire restricted property and will be subject to the state court process for approving conveyances of restricted land, it is important that legal practitioners in the state familiarize themselves with both the Stigler Act and its amendments.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Conor P. Cleary is senior Indian law attorney at the Office of the Solicitor, U.S. Department of the Interior. He received his LL.M. in American Indian law with highest honors from the TU College of Law and his J.D. from the OU College of Law.

1. Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, H.R. 2606, PL 115-399, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018).

2. Ch. 517, 30 Stat. 495 (June 28, 1898).

3. Compare, e.g., Original Creek Allotment Agreement, ch. 676, 31 Stat. 861 (March 1, 1901) and Supplemental Allotment Agreement, ch. 1323, 32 Stat. 500 (June 30, 1902) (providing for a 40-acre homestead allotment and 120-acre surplus allotment) with Cherokee Allotment Agreement, chap. 1375, 32 Stat. 716 (July 1, 1902) (providing for 110-acre allotments with a 40-acre homestead and 70-acre surplus allotment).

4. See, e.g., Creek Supplemental Agreement, chap. 1323, §16, 32 Stat. 500, 503 (1902) (“Each citizen shall select from his allotment forty acres of land ... as a homestead, which shall be and remain nontaxable, inalienable, and free from any incumbrance whatever for twenty-one years.”).

5. Allottees did not include only Indian members, but also intermarried white citizens and African-American freedmen.

6. Act of May 27, 1908, chap. 199, §1, 35 Stat. 312.

7. Id.

8. Id.

9. See, e.g., Act of April 21, 1904, chap. 1402, 33 Stat. 189, 204 (allowing secretary of the interior to remove restrictions on surplus lands of allottees upon application); Act of May 27, 1908, §1, 35 Stat. 312 (“[T]he Secretary of the Interior may remove such restrictions, wholly or in part, under such rules and regulations concerning terms of sale and disposal of the proceeds for the benefit of the respective Indians as he may prescribe.”).

10. See W.F. Semple, Oklahoma Indian Land Titles 87 (“Prior to the passage of the [Five Tribes Act of 1906], inherited lands could be sold, whether the heirs were full-blood or mixed-blood Indians.”). The exception was the Creek Supplemental Allotment which did not allow alienation of surplus lands by the allotee or his heirs for five years. See Creek Supplemental Agreement, chap. 1323, §16, 32 Stat. 500, 503 (June 30, 1902).

11. Act of May 27, 1908, chap. 199, §9, 35 Stat. at 315.

12. Id.

13. See Act of Aug. 4, 1947 (hereafter, the Stigler Act), chap. 458, §1(a), 61 Stat. 731 (“[N]o conveyance ... shall be valid unless approved in open court by the county court of the county in Oklahoma in which the land is situated.”).

14. Id.

15. Id., §1(a), 61 Stat. at 731. The only blood quantum that mattered for purposes of quantification was the degree of Five Tribes Indian blood possessed by the Indian landowner. As a result, an Indian landowner who was one-half Cherokee and one-fourth Navajo would be restricted, while an Indian landowner who was one-fourth Cherokee and one-half Navajo would not be restricted.

16. Id., §1(b), 61 Stat. at 731.

17. Angie Debo, And Still the Waters Run 51 (1940). The Five Tribes’ total acreage before allotment comprised 19,525,966 acres. 15,794,351.48 was allotted and 3,731,613.52 acres was unallotted or segregated from allotment. Id.

18. Statement of United States Department of the Interior Before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on H.R. 2606, Nov. 14, 2018, available at www.doi.gov/ocl/hr-2606-1 (last accessed July 12, 2019).

19. Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, H.R. 2606, PL 115-399, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018).

20. Statement of United States Department of the Interior Before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs on H.R. 2606, Nov. 14, 2018, available at www.doi.gov/ocl/hr-2606-1 (last accessed July 12, 2019).

21. The Stigler Act Amendments specify several methods of acquiring restricted property including inheritance, devise, gift, exchange, purchase, purchase with restricted funds, partition and partition sale. See Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018). The terms “purchase” and “partition sale” are newly added methods that did not appear in the original Stigler Act.

22. Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018). The final Indian rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory are the enrollment records of Indian persons compiled by the Dawes Commission. “Original enrollees” are those individuals whose names appear on such enrollment records. The final Indian rolls should be distinguished from the enrollment records of intermarried whites and freedmen, who were also members of the Five Tribes. Lineal descendants of original enrollees on the intermarried white or freedmen rolls are not eligible to acquire or inherit restricted property unless they also are lineal descendants of original enrollees on the final Indian rolls.

23. Another significant change in the Stigler Act Amendments is a provision allowing restricted property in the estate of someone dying before the enactment of the amendments, but whose estate is probated afterward, to descend in restricted status to the heirs, regardless of their blood quanta. See Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018).

24. The law governing probate of estates containing restricted land is also unchanged. Notice of such probates must continue to be served on the regional director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Eastern Oklahoma Regional Office in order to be valid.

25. Stigler Act Amendments of 2018, 132 Stat. 5331 (Dec. 31, 2018).

26. Id.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal -- OBJ 91 pg. 50 (January 2020)