Oklahoma Bar Journal

The Back Page | The Best Fee My Grandfather Ever Collected

By Mark S. Darrah

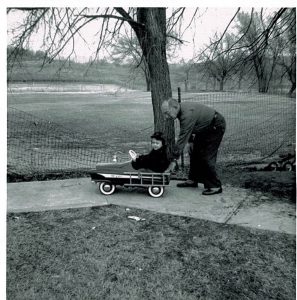

Young Mark with his grandpa

“An honest man can't make a living practicing law,” my grandmother said when I told her I had decided to go to law school. Her eyes had that glint they got when she spoke her truth and expected you to take it in and make it your own. “Your grandfather used to always say that being an attorney is the most dignified way in the world to starve to death.”

Her reaction surprised me. She had been married to a lawyer most of her adult life, and I would be the third generation in my family to practice law in Oklahoma. My grandparents never seemed to lack and lived with comforts many people didn't share. Grandpa had been a county judge through the Great Depression and World War II and went into private practice after the troops came home. During the latter part of his career, he was a government lawyer representing restricted Choctaws and Chickasaws in probate and related cases.

When he was in private practice, my grandfather had a second-floor office in a downtown building in the town where he lived. The oldest law firm in the county was at the opposite end of the hall. My father said that when people came up the stairs, those with good-paying work would turn right. The others would turn left and go to my grandfather's office.

Like many small-town lawyers in those days, Grandpa often worked for trade. A client would pay a fee with a sliver of mineral rights or a car engine overhaul. In the early 1950s, one client paid with a Deepfreeze Home Freezer, a then-revolutionary home appliance.

The dependable Deepfreeze

When my grandparents moved across the state, once Grandpa started working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the freezer was put into an outbuilding. Grandpa was a committed fisherman, and that freezer held a lot of crappie and bass.

I loved being with my grandfather when I was a little boy. He knew everyone. He had a story for every occasion. Going places with him was like being with a celebrity. Like most small-town lawyers, he devoted much of his free time to making his community better – to making the world a better place.

At the age of 64, Grandpa suffered a crippling stroke. His career ended. His voice was silenced. His Choctaw and Chickasaw clients stopped by his home and would call him "My Probate. My Probate."

After Grandpa died in 1976, that still-operating Deepfreeze became my mother's, who used it and used it and used it. The freezer still worked in 2002 when my parents moved out of their home into senior living. This was over 50 years after it satisfied the payment of a fee and after at least 438,000 hours of continual use.

My grandmother's words, I know now, were not a criticism of my career choice but an admonishment. A license to practice law is not a license to get rich, but if you are lucky, you might get a dependable Deepfreeze out of it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mr. Darrah is a general practice attorney in Tulsa. Donald B. Darrah, his grandfather, was Custer County judge from 1933 to 1947, in private practice in Clinton until 1958 and a U.S. trial attorney for the Department of the Interior until 1966. Oklahoma City lawyer Melissa J. Cottle is his great-granddaughter.

Originally published in the Oklahoma Bar Journal – OBJ 95 No. 10 (December 2024)

Statements or opinions expressed in the Oklahoma Bar Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Oklahoma Bar Association, its officers, Board of Governors, Board of Editors or staff.